Research Article - Neuropsychiatry (2018) Volume 8, Issue 4

A Systematic Review of Autism Spectrum in Children and Adolescents with 22q11.DS: Prevalence, Clinical Significance and Relationship with Onset of Psychotic Symptoms

- Corresponding Author:

- Maria Pontillo, PhD

Department of Neuroscience, Children Hospital Bambino Gesù, Piazza Sant’Onofrio 4, I-00165, Roma, Italy

Tel: +39-06-68592730

Fax: +39-06-68592450

Abstract

Background

22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) is a genetic syndrome associated with different neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Several studies reported contrasting data about prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in 22q1DS. Aim of our review was to summarize the evidence in literature on the prevalence and clinical significance of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in children and adolescents with 22q11DS. Subsequently, we also investigate the association between autism spectrum disorders and onset of psychotic symptoms in this clinical population.

Methods and findings

A systematic review of the literature published from 1970 to March 2018 was conducted. Nine studies are included. In particular, four of nine studies included reported elevated (10-40%) rates of autism spectrum disorders, including autism. However, in these studies the use of only parental report, not associated with the clinical direct observation, tends to overestimate the prevalence of ASD in children and adolescents with 22q11DS. Studies included on the relationship between ASD and psychosis in 22q11DS showed that early childhood autistic features (both ASD diagnosis and only presence of autistic symptoms) are not predictive of subsequent onset of psychotic symptoms.

Conclusion

Based on findings of this review, ASD-like behaviors are present in children and adolescents with 22q11DS and they are similar at the symptom level of idiophatic ASD. However, the social impairments in 22q11DS and idiophatic ASD could be expression of different neuropsychiatric picture. This should be considered in the planning of the treatment of the social impairments of 22q11DS.

Keywords

22q11.2 deletion syndrome, Autism spectrum disorders, Onset of psychotic symptoms

Introduction

22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) is a genetic syndrome caused by a microdeletion of the chromosome 22 band q11.2 with an estimated prevalence between 1:2,500 and 1:4,000, equally affecting male and female individuals [1,2].

This syndrome is associated with multiple congenital abnormalities such as cardiac malformations, vascular anomalies, velopharingeal insufficiency and cleft palate [3,4]. Developmental disabilities are also frequently identified, including speech and language delays and impairment on executive function, math, reading comprehension and visual spatial perception [3,5].

In addition, in children and adolescents with 22q11ds frequently are observed different neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Several studies [6,7] on children and adolescents with 22q11.ds showed high frequency of schizophrenia spectrum features and disorders (10%) indicating that psychosis is a clinical characteristic of this syndrome even in pediatric groups. However, in these studies, disorders typically diagnosed during childhood and adolescence have also been noted in 22q11ds: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, 12%-68%), oppositional defiant disorder (9%- 43%), and autism spectrum disorders (14%- 50%).

Regarding the latter, several studies have reported that at least 20% of children with 22q11ds are diagnosed with autism and, in addition, about 40-50% of 22q11DS receive a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder [8-12]. By contrast, 22q11 deletions are really infrequent in samples assessed with idiopathic autism [13]. Despite this, children with 22q11DS and children with only autism share similar neuroanatomic and neuropsychological phenotypes. Children with 22q11DS have smaller cerebellar volumes [14,15] and larger amygdala volumes [16]. Furthermore, subjects with 22q11DS demonstrate deficits in executive functions, which are commonly assumed as a core deficit in autism [17-19]. Language deficits are present both in 22q11DS and in autistic children, even if in 22q11DS it is less severe. Finally, children with 22q11DS and those with autism show a similar higher predisposition to psychopathology [4,22-25].

Indeed, disturbances of emotion, attention, activity, thought, and associated behavioral problems occur in children with autism of all ages. Regarding this, in Leyfer [25] were reported high frequency for anxiety disorders (44%, especially specific phobia), obsessive compulsive disorders (37%), mood disorders (14%) and behavioural disorders (7%).

Overall, although phenotypes of 22q11DS and autism overlapping, few studies investigated the clinical significance of autism spectrum disorders in children with 22q11DS.

For example, different authors suggest that the presence of autistic symptoms like the social communication deficits and the repetitive behaviors detected in 22q11DS children may be early prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia [15,26-28].

Based on this, we firstly carried out a review to summarize the evidence in literature on the prevalence and clinical significance of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in children and adolescents with 22q11DS. Subsequently, we investigate the association between autism spectrum disorders and onset of psychotic symptoms in this clinical population.

Materials and Methods

▪ Study design

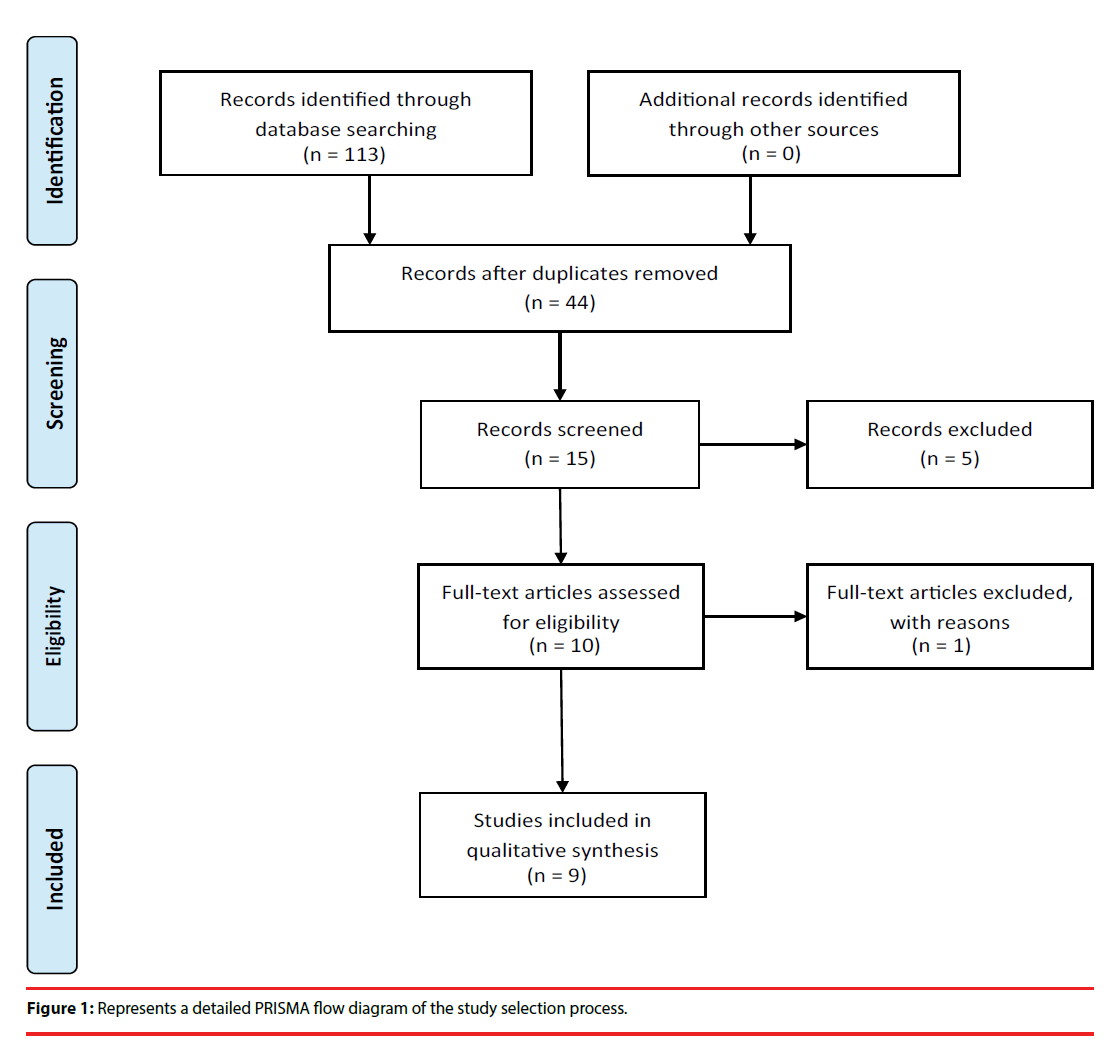

This paper includes a systematic review of the literature published from 1970 to March 2018. The authors followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [29].

▪ Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search of the PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINHAL), PsycINFO, ClinicalTrial. gov databases was conducted. A search algorithm based on a combination of these terms was used: (DiGeorge syndrome OR Velocardiofacial syndrome OR 22q11.2 deletion syndrome) AND (Autism spectrum disorders OR Autism spectrum OR Autism OR Autistic Disorders) AND (Schizophrenia OR Early Onset Psychosis OR Early Onset of Psychosis Symptoms). The last update of the search was done at the beginning of March 2018.

▪ Selection criteria

Studies were included if they investigated the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in children and adolescents with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Consequently, we included only studies where the autism spectrum disorders in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome were assessed using any psychometrical validated scale [30-33] and were diagnosed using any recognized diagnostic criteria [34-36].

Articles not in the area of interest of this review were excluded (e.g. review articles, editorials or letters, comments, conference proceedings and studies on treatments). No language limits or study design limits were used.

▪ Selection procedure, data extraction and data management

OS, MCT and FD analysed singularly the complete literature present on the theme, also screened the bibliographies of the most relevant publish articles. Data on efficacy, acceptability and tolerability were extracted by two authors independently (SG e PG). Disagreements were resolved in a consensus meeting by other reviewers (MP, SV and RA). The search algorithm resulted in 44 articles, of which 15 referred to potentially eligible studies. Of these, 6 articles were non-empirical studies, reviews and commentaries. In terms of evidence-based medicine, the quality of these studies was moderate (Figure 1).

▪ Data synthesis

We found a total pool of nine studies on autism in children and adolescents with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Due to the low number of included studies, we proposed a narrative synthesis. The narrative synthesis required describing, organizing, exploring and interpreting the study findings, examining their methodology adequacy. Where particular patterns of findings have emerged, we have presented possible explanations for these findings.

Results

To 1970 from March 2018, nine studies have been conducted, proving results about the prevalence and the clinical significance of autistic spectrum disorders in children and adolescents with 22q11DS. Details on the methodologies and results of the studies are shown in Table 1.

| Study | Sample | Methods | Criteria for diagnosis | Measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine et al. [9] | N=98 Range age: 2-12 |

Experimental study |

DSM-IV ICD -10 |

ADI-R [48] M-CHAT SCQ VABS |

Over 20% of children (n = 22) were exhibiting significant levels of autism spectrum symptoms based on the M-CHAT and SCQ. Of these, 14% met criteria for an ASD diagnosis based on ADI-R. |

| Angkustsiri et al. [38] | N=29 Mean age: 10.7 SD:2.1 Mean IQ: 74.6 N=100 Mean age: 10.7 SD: 2.4 Mean IQ: 75.6 |

Experimental study |

ADOS SCQ BASC-2 PRS |

ADOS SCQ BASC-2 PRS WISC IV [62] |

18 % of 29 children scored in the elevated range on the ADOS. Only 2 (7 %) of the 29 had SCQ scores above the cut-off of 15. No child had both SCQ and ADOS scores in the elevated range. 44% of 100 children with 22q11.2DS screened positive based on an atypicality T score; 51 % had elevated withdrawal T scores; 68 % had elevated T scores on the Developmental Social Disorders scale. 80% of the first study participants with positive ADOS (n = 4) had also elevated BASC-2 PRS anxiety and/or somatization scores. |

| Niklasson et al. [40] | N=100 ASD=52 Non ASD=37 Range age: 84<16 |

Experimental Study | DSM IV criteria | WPPSI-R [63] WISC-III [61] WAIS-R GMDS [52] VABS ASSQ BPRS CBCL FTF [50] |

21% of the subjects received a diagnosis of ADHD, 14% of ASD and 9% of the sample presented a combination of ADHD and ASD. Within the 23% of ASD presence, 5% presented an Autistic Disorder, 17% an Autistic Like Condition and only 1% Asperger Syndrome (p<0.02). |

| Antshel et al. [3] | N=41 Range age: 6.5-15-8 Mean Age: 10.6 SD=2.4 |

Experimental Study | ADI-R VABS WISC-III SB-IV [55] |

ADI-R K-SADS-PL YMRS-PV [57] CBCL VABS BASC WISC-III VST [56] WCST GDS [51] |

94% of children with 22Q11DS + ASD had a comorbid psychiatric diagnoses in comparison to 60% of children with 22Q11DS (p = 0.026). The sample of 22Q112DS+ASD exhibited more odd/repetitive behaviors on the BASC-2 PRS (p = 0.018), less socialization as indexed on the VABS Socialization scale (p = 0.004) and had more social difficulties on the CBCL (p = 0.002). For Executive Functioning Profile made more non perseverative errors (p = 0.008). |

| Kates et al. [3] |

N=41 Range Age: 6.5-15.8 Mean Age: 10.6 SD=2.4 |

Experimental Study | ADI-R VABS WISC-III SB-IV |

ADI-R VABS WISC-III SB-IV |

Degree of communication deficits and idiosyncratic speech in VCFS+autism was less severe than those with idiopathic autism(p<0.001). 22q11DS+autism comparing with the sample had less make-believe play and more repetitive/stereotyped interested (p<0.001). |

| Mc Cabe et al. [43] | N=65 ASD group N=14 Range Age: 11-20 22q112DS group N=20 Range Age: 8-21 Control group N=31 Range Age: 11-22 |

Experimental Study | DSM IV -TR SCQ SDQ SCID [53] |

K-SADS-PL WASI [59] SCQ SDQ [54] FERT WSRT |

22q11DS sample and ASD sample had lower intellectual functioning (p<0.001) compared to TD sample. FERT: ASD and 22q11DS groups had fewer fixations across emotion stimuli (ASD: p=0.003; 22q11DS: p=0.01) but did not differ from each other in terms of number of fixations (p>0.05). WSRT: ASD group showed fewer fixations to stimuli compared to the TD group (p=0.04). The 22q11DS group differed in recognition accuracy compared to both group (ASD/TD: p=0.001; 22q11DS/TD: p=0.0001) |

| Fiksinki et al. [44] | N=89 ASD=52 Non ASD=37 Mean age: 14.3 SD: 1.9 |

Longitudinal study |

DSM IV criteria | K-SADS PL ADI-R WISC-III WISC-R [60] WAIS-III [58] |

No significant difference in the proportions of patients who developed psychotic symptoms between ASD-group and non-ASD group (p =0.963). |

| Vorstman et al. [12] | N=60 23 males 37 females Mean age= 13.7 SD= 2.7 IQ= 65.2 SD = 13.9 |

Longitudinal study |

DSM IV criteria | K-SADS PL WISC III WISC-R WAIS-III ADI-R CPRS [49] CTRS CBCL Teacher Rating Form CBCL Parent Form |

High rates of autism spectrum disorders (30 of 60, 50.0%) and psychotic symptoms (16 of 60, 26.7%) were found in this sample. In 7 of 60 (11.7%), the psychotic symptoms interfered with behavior and caused considerable distress. Difference was detected between children with and without a psychotic disorder (p = 0.046), while no differences were found comparing subgroups with and without any psychiatric disorder (p = 0.477). |

| Vorstman et al. [46] | N=77 with 22Q11DS 36=psychotic disorder Mean age: 36.6, Mean IQ: 69.7, 47.2% male 41= no history of a psychotic illness Mean age: 28.5, Mean IQ: 75.7, 53.7% male |

Longitudinal study |

DSM IV criteria | SRS SCQ |

Two groups did not differ on SRS and SCQ. These findings indicate that autistic features in childhood cannot be used as a marker that can predict the development of schizophrenia in 22q11.2DS. |

Table 1: Results of included studies.

▪ Autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents with 22q11DS: Prevalence and clinical significance

From 1970 to March 2018, six studies have been conducted, with results proving the prevalence and the clinical significance of ASD in children and adolescents with 22q11DS.

Fine [9] investigated the presence of autism spectrum disorder in a sample of 98 children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (range age: 2-12 years). ASD was assessed through caregivers report using firstly M-CHAT or SCQ depending on the age of the child and VABS [37]. Secondly, ADI-R has been given to parents of children who obtained significant results in the first assessment or had a previous diagnosis of autism. The results showed that over 20% of 22q11DS (n=22) were exhibiting significant levels of autism spectrum symptoms based on M-CHAT and SCQ. Of these, 14% (range age: 3.24-11.53; 85.7% male) met criteria for an ASD diagnosis based on ADI-R. Indeed, their caregivers reported behaviors that exceeded the cut-off points in several domains of scale (e.g. communication, social relatedness, and repetitive or stereotyped patterns of behavior), which qualified presence of ASD.

The aim of Angkustsiri was to investigate the prevalence of ASD in a sample of children with 22q11.DS through two different studies [38].

In the first, 29 children with 22q11DS (mean age: 10.7 ± 2.1 years; mean IQ: 74.6) were assessed with ADOS and SCQ with the aim of formulate an ASD diagnosis based on clinical diagnostic criteria. Results showed that 7% of the sample (n=2) had significant results in SCQ, 15% (n=4) could be classified as ASD in ADOS and 3% (n=1) could be classified as autism in ADOS. No one had positive score in both SCQ and ADOS. Through ADOS the authors classified strengths and weakness of participants. In particular, 22q11DS with positive ADOS presented social communication as a strength and communication area as a weakness point, in particularly in conversation, gestures, insight and imagination.

In the second study, ASD diagnosis was based on BASC-2 PRS [39], a parental report questionnaire.

The sample was composed of 100 children with 22q11DS (mean age: 10.7 ± 2.4 years; mean IQ: 75.6), including the 29 of the first study. Results showed that 44% of the sample had significant scores in atipicality, 51% had elevated withdrawal scores and 68% had elevated scores on the Developmental Social Disorders scale. In addition, 80% of participants of the first study with positive ADOS (n=4) had also elevated BASC-2 PRS anxiety and/or somatization scores.

The aim of Niklasson was to estimate the prevalence of ASD and the other neuropsychiatric comorbidities in one-hundred consecutively referred children, adolescent and young adults with 22q11.2DS (age range: 1–35 years) [40].

Participants underwent a depth neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological evaluation to collect information about physical health, infant psychomotor and speech development, social skills, familiar history, cognitive ability and other unusual behaviors.

The results showed that in this cohort, 21% of the subjects received a diagnosis of ADHD, 14% of ASD and 9% of the sample presented a combination of ADHD and ASD. Within the 23% of ASD presence, only 5% presented an Autistic disorder, 17% Autistic Like Condition and only 1% Asperger syndrome (p<0.02).

Antshel [23] examined the cognitive, behavioural and neuroanatomical differences between two groups: the first group was composed of 17 children with 22q11DS+ ASD (mean age: 10.4 ± 1.9, 59% male) [41] the second group was composed of 24 children with 22q11DS only (mean age: 10.8 ± 2.7, 46% male). Autism spectrum disorder was assessed by the ADI-R and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans were acquired for measure the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and cerebellum.

Results showed that the first group of children with 22q11DS + ASD presented also more odd/ repetitive behaviours (BASC-2 PRS: A typicality scale, F (1, 39)=9.57, P=0.004), less socialization (VABS: Socialization scale, F (1, 39)=6.15, P=0.018) and had more social difficulties with their peers (CBCL: Social Problems, F (1, 39)=11.59, P=0.002) (Child Behavior Checklist) compared to the second group with 22q11DS only [42]. For executive functions, children with 22q11DS + ASD made more non perseverative errors (WCST, F (1, 39)=7.85, P=0.008) [42]. Regarding neuroanatomical differences between groups, there were not brain volume differences between the two groups (F (1, 39)=1.79, P=0.192), but the children with 22Q11DS + ASD had a larger right amygdala volumes than children with 22Q11DS (F (1, 39)=9.21, P=0.005).

Regarding the psychiatric diagnosis associated, results of Antshel showed that the 94% of children with 22q11DS + ASD had a comorbid psychiatric disorder in comparison to the 60% in children with 22q11DS only (p=0.026) [5]. ADHD was the most frequently psychiatric disorder in both groups, but it was present twice as often in the first group of children with 22q11DS + ASD (80%, p=0.020). In addition, these children presented also more specific phobias (60%, p=0.08) and mania symptoms (F (1, 39)=8.23; p=0.007).

The aim of Kates was to examine the behavioral phenotype in children and adolescents with idiopathic autism and in children and adolescents with 22q11DS+autism [3].

Five groups of children and adolescents were included in this study: 33 with 22Q11DS (mean age: 10.6 ± 2.4 years; mean IQ: 77.2); 8 with 22Q11DS+autism (mean age: 10.7 ± 2.5 years; mean IQ: 68.1); 14 with idiopathic autism (mean age: 8.8 ± 2.6 years; mean IQ: 72.0); 14 community control (mean age: 10.8 ± 2.9 years; mean IQ: 99.2); 12 sibling control (mean age: 12.0 ± 2.2 years; mean IQ: 105.4). Siblings were included to control familial/shared environmental effects on the cognitive and behavioral phenotype of sample with 22Q11DS.

Autism diagnoses were based on ADI-R and adaptive behavior was analyzed through VABS. The results showed that relative to the non-autistic 22q11DS group, the siblings and the community controls, the two autism groups (children with autism idiopathic and 22q11DS+autism) had higher levels of parent reported reciprocal social interaction deficits, communication deficits and stereotyped behaviors. Although the two autism groups did not differ in degree of deficit in either reciprocal social interaction or stereotyped behaviors, post-hoc analyses revealed that degree of communication deficits (F (12, 193)=12.52, P<0.001) and idiosyncratic speech (F (16,211)=7.56, P<0.001) in children with 22q11DS + autism tended to be less severe than those with idiopathic autism. Comparing instead the sample with only 22Q11DS and the sample with 22Q11DS+autism, the children with 22Q11DS+autism had less make-believe play (F (16,211)=7.56, P<0.001) and more repetitive/ stereotyped interested (F (16,217)=7.19, P<0.001).

Finally, McCabe examined whether people with ASD and 22q11DS show the same pattern of scanpaths and emotion recognition deficits to facial displays of emotion [43].

The sample consisted of three groups: 14 adolescents with ASD (mean age: 14.71 ± 2.87 years; mean IQ: 92.5, 85.7% male); 20 adolescents with 22q11DS (mean age: 16.75 ± 3.71 years; mean IQ: 73.75, 35% male) and 31 typically developing (TD) adolescents (mean age: 16.55 ± 3.33 years; mean IQ: 107.73, 45.2% male). No participants with 22q11DS were diagnosed with ASD.

Participants underwent a depth neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological evaluation. In particular, Face Emotion Recognition Task (FERT) and the Weather Scene Recognition Task (WSRT) were used to explore visual scan path strategy and concurrent recognition accuracy.

Results firstly showed that 22Q11DS sample and ASD sample had lower intellectual functioning (F (2,63)=29.0, p<0.001) compared to TD sample. Analyzing FERT results, ASD and 22q11DS groups had fewer fixations across emotion stimuli (ASD: F (1,44)=10.7, p=0.003; 22q11DS: F(1,50)=9.03, p=0.01), but did not differ from each other in terms of the number of fixations (p>0.05). Moreover, the 22q11DS group paid significantly less attention to combined feature regions (eyes, nose, mouth) (F (2,61)=5.14, p=0.009) and well time to feature regions was influenced by the emotion content of the stimuli (F(6,56)=2.45, p=0.04). ASD group and 22q11DS group did not differ in accuracy (F (1,32)=2.2, p=0.15) but this two groups were significantly less accurate compared to the TD controls (ASD/TD: F(1,43)=6.7, p=0.03; 22q11DS/TD:F(1,48)=29.1, p=0.0001). Analyzing WSRT results, only the ASD group showed significantly fewer fixations to stimuli compared to the TD group (F(1,43) =4.49, p=0.04). The duration of fixation did not differ between the three groups (p>0.05). The 22q11DS group differed in recognition accuracy compared to both groups (ASD/tipically developing adolescents: F (1,32)=10.9, p=0.001; 22q11DS/TD: F(1,48)=17.9, p=0.0001).

▪ Autism spectrum disorders and onset of psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents with 22q11DS

From 1970 to March 2018, three studies had been conducted, that examined the association between autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents with 22q11DS and onset of psychotic symptoms.

Fiksinki, in a prospective longitudinal study, investigated the possible development of a psychotic disorder in children with 22q11DS and a diagnosis and/or symptoms of ASD [44]. The sample consisted in 89 children (mean age: 14.3 ± 1.9) with 22q11DS that were divided in two groups based on the presence or not presence of ASD. Every group was evaluated at baseline and after 3-4 years for follow-up. At baseline, there were 52 (58.4%) participants in the ASD and 37 (41.6%) in the non-ASD group.

Assessment comprehended ADI-R, used to assess ASD and evaluating both current and early childhood autistic behaviors and K-SADS-PL, used to determine development of a psychotic disorder or psychotic symptoms [45].

The results revealed no significant predictive effects of a diagnosis of ASD on the subsequent development of a psychotic disorder (p=0.270). The findings remained similar when age, gender and Full scale of IQ were added to the regression model (p=0.235). In fact, in the ASD group the proportion of individuals who developed a psychotic disorder (17.3%, n=9) was lower than in the non-ASD group (27%, n=10) (p=0.963).

Subsequently, Fiksinki investigated the association between the severity of autistic symptoms and the subsequent development of psychotic disorders, regardless the presence or not of a formal ASD diagnosis [44]. Results demonstrated no predictive effect of autistic symptom severity in the domains of social interaction, communication and repetitive behaviors in the development of subsequent psychotic disorder. In particular, there were no significant results in comparison between ASD symptoms severity at baseline and both the group with psychotic symptoms (mean: 22.8 ± 15.6) and the group without psychotic symptoms (mean: 23.9 ± 12.7) (p=0.835). Use of psychopharmacological medications and antipsychotics during the interval time was similar between two groups (baseline: 30.8% ASD vs. 16.2% non-ASD, p=0.117; follow-up: 19.2% ASD and 13.5% non-ASD, p=0.478).

Vorstman [12] examined the relationship between ASD and 22q11DS in a cross-sectional study that is part of a prospective longitudinal research that wanted to examine the question if the psychiatric disorders reported in children with 22q11DS should be considered as independent phenomena or, alternatively, as markers of an increased vulnerability for schizophrenia in adulthood. The sample (n=60) consisted of 23 males and 37 females (mean age: 13.7 ± 2.7 years, mean IQ: 65.2) with 22q11DS. Assessment was based on semistructured interview and standardized questionnaires (e.g. K-SADS-PL and ADI-R) to collect information by child, caregivers and teacher about presence of autistic features, unusual behavior and cognitive ability.

High rates of autism spectrum disorders (30 of 60 patients, 50.0%) and psychotic symptoms (16 of 60 patients, 26.7%; mean age: 14.2 ± 2.4 years) were found in this sample. Regarding autism symptomatology, 27 children were diagnosed pervasive development disorder not otherwise specified and 3 with autism. Observing ADI-R scores, 33.3% of the patients obtained significant scores in three domains (social interaction, communication and stereotyped behaviors), 11.7% in two domains and 20% in one domain. Regarding psychotic symptomatology, instead, 16 patients (26.7%) presented hallucinations and/or delusions. In 7 of 60 (11.7%), the psychotic symptoms interfered with behavior and caused considerable distress. In these cases, the diagnosis of a psychotic disorder was applied. A significant difference was detected comparing mean intelligence level between children with and without a psychotic disorder (p=0.046), suggesting that a low IQ could be a risk factor for psychosis in children and adolescent with 22q11DS. No differences were found comparing subgroups with and without any psychiatric disorder (p=0.477). Examining correlation between IQ level and severity of autistic symptoms and psychotic symptoms, no relevant correlations were found (IQ level and autistic symptoms: r=- 0.093, p=0.486; IQ level and psychotic symptoms: r=-0.060, p=0.656).

Vorstman examined the relation between autism and schizophrenia in patients sharing the same copy number variants (CNV) to determinate if autistic symptoms during childhood were associated with psychosis in adulthood [46]. 77 adults with 22Q11DS were divided in two groups: 36 formed the schizophrenia group (mean age: 36.6, mean IQ: 69.7, 47.2% male) and 41 with no history of a psychotic illness formed the comparison group (mean age: 28.5, mean IQ: 75.7, 53.7% male). To analyze autistic behaviors in childhood, parents were asked to complete SRS and SCQ, using a “reference age” to complete the assessment (schizophrenia group: mean age 5.9 ± 2.0; comparison group: mean age: 6.4 ± 2.0; p=0.217) [47]. Results showed that the two groups did not differ on score in both parent report questionnaire. In particular, based on SRS, 75% of subject in schizophrenia group and 78% of comparison group could be classified as probable ASD (p=0.75). Based on SCQ cut-off 12, 36.1% of subject in schizophrenia group and 34.1% of comparison group could be classified as probable ASD (p=0.86), whereas based on SCQ cut-off 15, 8.3% of subject in schizophrenia group and 16.9% of comparison group could be classified as probable ASD (p=0.06).

Discussion

The first goal of this systematic review was to contribute to summarize the evidence in literature on the prevalence and clinical significance of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in children and adolescents with 22q11DS.

Four of the nine studies included reported elevated (10–40%) rates of autism spectrum disorders, including autism [23,9,12,40]. Despite this elevated rates, high ADI-R scores in at least two domains were present in only 14% of the largest sample (N=98) of Fine in 21% of 41 children with 22q11DS examined by Antshel and in 45% of 60 children with 22q11DS examined by Vorstmann [9,12,23].

In addition, reports by Niklasson rated ASD at 20-40% with autism present in only 3-5% of participants. Based on our review of this literature, it seems possible that differences between study design and especially diagnostic procedure is the reason for the discrepancy on prevalence of ASD in 22q11DS reported by different studies. Indeed, Antshel, Fine and Vorstmann used ADI-R for ASD diagnosis in 22q11DS rather than a more comprehensive diagnostic procedure that include also a direct observation based on ADOS. Indeed, as proposed by Angkutsiri [38] the only parental report based on ADI-R or SCQ could tend to overestimate ASD compared with more comprehensive clinical assessment that also incorporate direct behavioral observation conducted by experts clinicians [9,12,23,38]. To date, Angkutsiri is the first and only study that calculate ASD prevalence in 22q11ds using a combination of the ADOS and parental report measured with SCQ [38]. The results showed that not one child with 22q11DS in the sample examined met strict diagnostic criteria using both the ADOS and SCQ. In addition, 80% of participants with positive ADOS had also elevated BASC-2 PRS scores for anxiety and/or somatization dimensions. This finding suggest that using a clinical procedure including history reported by parents (SCQ) and a standardized observation measure (ADOS) the prevalence of ASD in 22q11DS is not as high as reported in Fine, Antshel and Vorstmann. If the results of the study of Angkutsiri will be replicated, this could indicate that impairments in social behavior reported in previous studies are not really ASD symptoms but deficit in social skills associated to behavioral phenotype of syndrome. About this, Kates and McCabe reported qualitative differences in social impairments of 22q11DS compared with idiophatic ASD [3,43]. In Kates, children with autism idiopathic and children with 22q11DS and autism not differ in degree of deficit in either reciprocal social interaction or stereotyped behaviors; however, degree of communication deficits and idiosyncratic speech in children with 22q11DS and autism tended to be less severe than those with idiopathic autism. McCabe found that in a tasks comparing scanpath patterns the ASD and 22q11DS groups displayed a similarly reduced number of fixations to face emotion stimuli compared to controls. When McCabe examined where participants allocated their attention, the ASD group did not differ compared to the controls whilst the 22q11DS group spent significantly less time viewing salient regions overall [3,43].

The authors conclude that if 22q11DS group could be characterized by a generalized processing deficit, the ASD group could be present a susceptibility to the unique complexity of faces, rather than particular difficulty with object discrimination tasks.

Regarding the relationship between ASD and onset of psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents with 22q11DS, all three studies included in our review show no association between ASD and the subsequent development of psychosis in 22q11DS [12,44,46]. In the prospective study of Fiksinki early childhood autistic features (both ASD diagnosis and only presence of autistic symptoms) are not predictive of subsequent onset of psychotic symptoms [44]. These findings replicate those of previous retrospective study conducted by Vorstmann in which the subgroup of 22q11DS with probable ASD during childhood did not show an increased risk for psychosis in adulthood. Finally, in Vorstmann no correlation was found between autistic symptoms and onset of psychotic symptoms.

Overall, all these three studies indicate that ASD and psychotic disorders should be considered as relatively independent neuropsychiatric characteristics of 22q11DS and that in these clinical population autistic features in childhood cannot be used as a marker that can predict the development of psychosis in 22q11.2DS.

▪ Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review that critically analyzes the question, existing in the literature, about the role of ASD in 22q11DS in terms of prevalence, clinical manifestations and relationship with onset of psychotic symptoms.

Some limitations should be considered in our review. Firstly, the number of included studies is low. Secondly, there is a discordance of study design and measures for clinical assessment between the included studies. Both these limitations do not allow a quantitative analysis of the results.

▪ Research and clinical implications

Based on findings of this review, ASD-like behaviors are present in children and adolescents with 22q11DS and they are similar at the symptom level of idiopathic ASD; however, the social impairments in 22q11DS and idiopathic ASD could be expression of different neuropsychiatric picture. Future studies should be conducted to clarify this. For example, the true prevalence of ASD in 22q11DS could be investigated integrating multiple sources of information (Clinical direct observation, parental report). Using these multiple source for the assessment could be clarifying also the qualitative differences between ASD-like behaviors in 22q11DS and idiophatic ASD. This last point would be relevant for the planning of treatment of social impairments in 22q11DS.

References

- Goldenberg PC, Calkins ME, Richard J, et al. Computerized neurocognitive profile in young people with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome compared to youths with schizophrenia and at-risk for psychosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet 159(1), 87-93 (2012).

- Oskarsdóttir S, Vujic M, Fasth A. Incidence and prevalence of the 22q11 deletion syndrome: a population-based study in Western Sweden. Arch. Dis. Child 89(2), 148-151 (2004).

- Kates WR, Antshel KM, Fremont WP, et al. Comparing phenotypes in patients with idiopathic autism to patients with velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11 DS) with and without autism. Am. J. Med. Genet 143(22), 2642-2650 (2007).

- Swillen A, Devriendt K, Legius E, et al. Intelligence and psychosocial adjustment in velocardiofacial syndrome: a study of 37 children and adolescents with VCFS. J. Med. Genet 34(6), 453-458 (1997).

- Antshel KM1, Kates WR, Roizen N, et al. 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome: Genetics, neuroanatomy and cognitive/behavioral features. Child. Neuropsychol 11(1), 5-19 (2005).

- Schneider M, Debbané M, Bassett AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders from childhood to adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: results from the International Consortium on Brain and Behavior in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 171(2), 627-639 (2014).

- Tang SX, Yi JJ, Calkins ME, et al. Psychiatric disorders in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome are prevalent but undertreated. Psychol. Med 44(6), 1267-1277 (2014).

- Chudley AE, Gutierrez E, Jocelyn LJ, et al. Outcomes of genetic evaluation in children with pervasive developmental disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr 19(1), 321-325 (1988).

- Fine SE, Weissman A, Gerdes M, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and symptoms in children with molecularly confirmed 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord 35, 461-470 (2005).

- Niklasson L, Rasmussen P, Oskarsdóttir S, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders in the 22q11 deletion syndrome. Genet. Med 3(1), 79-84 (2001).

- Roubertie A, Semprino M, Chaze AM, et al. Neurological presentation of three patients with 22q11 deletion (CATCH 22 syndrome). Brain. Dev 23, 810-814 (2001).

- Vorstman JA, Morcus ME, Duijff SN, et al. The 22q11.2 Deletion in Children. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 45(9), 1104-1113 (2006).

- Ogilvie CM1, Moore J, Daker M, et al. 2000. Chromosome 22q11 deletions are not found in autistic patients identified using strict diagnostic criteria. IMGSAC. International Molecular Genetics Study of Autism Consortium. Am. J. Med. Genet 96(1), 15-17 (2000).

- Eliez, S., Blasey, C.M., Schmitt, E.J., et al. Velocardiofacial syndrome: are structural changes in the temporal and mesial temporal regions related to schizophrenia? Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 447-453 (2001).

- van Amelsvoort T, Daly E, Henry J, et al. 2004. Brain anatomy in adults with velocardiofacial syndrome with and without schizophrenia: preliminary results of a structural magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61(11), 1085-1096 (2004).

- Kates WR, Miller AM, Abdulsabur N, et al. Temporal lobe anatomy and psychiatric symptoms in velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 45(2), 587-595 (2006).

- Bearden CE, Jawad AF, Lynch DR, et al. 2004. Effects of a functional COMT polymorphism on prefrontal cognitive function in patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 161(1), 1700-1702 (2004).

- Hill EL. Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends Cogn. Sci 8(1), 26-32 (2004).

- Ozonoff S, Pennington BF, Rogers SJ. Executive function deficits in high-functioning autistic individuals: relationship to theory of mind. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 32(1), 1081-1105 (1991).

- Pennington BF, Ozonoff S. Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 37, 51-87 (1996).

- Glaser B, Mumme DL, Blasey C, et al. Language skills in children with velocardiofacial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2). J. Pediatr 140, 753-758 (2002).

- Antshel KM, Fremont W, Roizen NJ, et al. 2006. ADHD, Major Depressive Disorder, and Simple Phobias Are Prevalent Psychiatric Conditions in Youth With Velocardiofacial Syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 45(5), 596-603 (2006).

- Antshel, K.M., Aneja, A., Strunge, L., et al. Autistic spectrum disorders in velo-cardio facial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion). J. Autism Dev. Disord 37, 1776-1786 (2007).

- Gerdes M, Solot C, Wang PP, et al. Cognitive and behavior profile of preschool children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion. Am. J. Med. Genet 85(, 127-133 (1999).)

- Leyfer OT, Folstein SE, Bacalman S, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: interview development and rates of disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord 36, 849-861 (2006).

- Crespi B, Badcock C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behav. Brain. Sci 31, 241-320 (2008).

- Eliez S. Autism in Children with 22Q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 46, 433-434 (2007).

- Karayiorgou M, Simon TJ, Gogos JA. 22q11.2 microdeletions: linking DNA structural variation to brain dysfunction and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 11, 402-416 (2010).

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS. Med 6, e1000097 (2009).

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, et al. Autism diagnostic observation schedule-WPS (ADOS-WPS). Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles, CA (1999).

- Ehlers S, Gillberg C, Wing L. A screening questionnaire for Asperger syndrome and other high-functioning autism spectrum disorders in school age children. J. Autism Dev Disord. 29, 129-141 (1999).

- Robins DL, Fein D, Barton ML, et al. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: an initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord 31, 131-144 (2001).

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord, C. The social communication questionnaire: Manual. Western Psychological Services, Los Angels, CA (2003).

- World Health Organization, The ICD-10. Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland (1993).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. APA, Arlington, VA (2013).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision. APA, Washington, DC (2000).

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cichetti DV. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. AGS, Circle Pines, MN (1983).

- Angkustsiri K, Goodlin-Jones B, Deprey L et al. Social impairments in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS): Autism spectrum disorder or a different endophenotype? J. Autism Dev. Disord 44, 739-746 (2014).

- Volker MA, Lopata C, Smerbeck, et al. BASC-2 PRS profiles for students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord 40, 188-199 (2010).

- Niklasson L, Rasmussen P, Óskarsdóttir S, et al. Autism, ADHD, mental retardation and behavior problems in 100 individuals with 22q11 deletion syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil 30, 763-773 (2009).

- Achenbach T. Child behavior checklist. ASEBA, Burlington, VT (1991).

- Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, et al. Wisconsin card sort test manual: Revised and expanded. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc, Odessa, FL (1993).

- McCabe KL, Melville JL, Rich D, et al. 2013. Divergent patterns of social cognition performance in autism and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS). J. Autism Dev. Disord 43, 1926-1934 (2013).

- Fiksinski AM, Breetvelt EJ, Duijff SN, et al. Autism Spectrum and psychosis risk in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Findings from a prospective longitudinal study. Schizophr. Res 188, 59-62 (2017).

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36 (2), 980-988 (1997).

- Vorstman JAS, Breetvelt EJ, Thode KI, et al. Expression of autism spectrum and schizophrenia in patients with a 22q11.2 deletion. Schizophr. Res 143(1), 55-59 (2013).

- Constantino JN, Gruber C. The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). Manual Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles (2005).

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord 24, 659-685 (1994).

- Conners CK. Conners Rating Scales-Revised. Multi-Health Systems Publishing, North Tonawanda, NY (1997).

- Kadesjo B, Janols LO, Korkman, M, et al. The FTF (Five to Fifteen): the development of a parent questionnaire for the assessment of ADHD and comorbid conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 13, 3-13(2004).

- Gordon M, McClure FD, Aylward GP. Gordon diagnostic system. Gordon Diagnostic Systems,Dewitt, NY (1989).

- Ahlin-Akerman B, Nordberg L. Griffiths Utvecklinsskalor. Psykologiforlaget AB, Stockholm (1980).

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for dsm-iv-tr axis i disorders, research version, patient edition with psychotic screen (scid-i/pw/psy screen). Biometrics Research, New York (2002).

- Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons, H, et al. Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. Br. J. Psychiatry 177, 534-539 (2000).

- Thorndike RL, Hagen EP SJ. Stanford-Binet intelligence scale, 4th ed. Riverside Publishing, Itasca, IL (1986).

- Davis HR. Colorado assessment tests- visual span test. Colorado Assessment Tests, Boulder, CO (1998).

- Gracious BL, Youngstrom EA., Findling RL, et al. Discriminative validity of a parent version ofthe Young Mania Rating Scale. JAACAP 41, 1350–1359 (2002).

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III Administration and scoring manual. The Psychological Association., San Antonio, TX (1997).

- Wechsler D. Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. The Psychological Corporation., San Antonio, TX (1999).

- Wechsler D., 1974. Wechsler intelligence scale for children-Revised. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX.

- Wechsler D.Wechsler intelligence scale for children, 3rd ed. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX (1991).

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 4th ed. The Psychological Corporation., San Antonio, TX (2003).

- Wechsler D. Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence scale-Revised.Psychological Corporation, New York (1989).