Review Article - Imaging in Medicine (2013) Volume 5, Issue 3

Abdominal ultrasound findings in HIV and tuberculosis

Michael Grace Kawooya*Ernest Cook Ultrasound Research & Education Institute (ECUREI), Kampala, Uganda

- Corresponding Author:

- Michael Grace Kawooya

Ernest Cook Ultrasound Research & Education Institute (ECUREI)

Kampala, Uganda

E-mail: kawooyagm@yahoo.co.uk

Abstract

Keywords

HIV/AIDS ▪ tuberculosis ▪ ultrasound

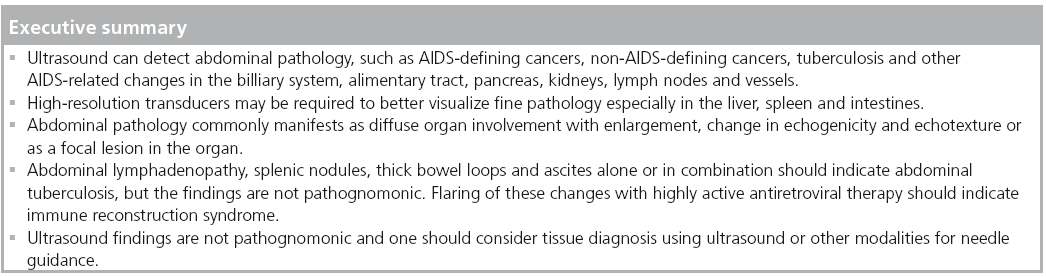

AIDS was first recognized in the early 1980s as a disease entity caused by a virus (HIV) and manifesting as a complex collection of clinical features due to the primary HIV infection plus related comorbidities. Currently with wide application of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the disease pattern has furthermore changed. Ultrasound (US) is often the most available, most accessible and often the initial imaging modality for HIV patients with abdominal symptoms. Over the past two decades, numerous studies, in various parts of the world, have documented the complex, yet informative and clinically useful abdominal US findings in HIV/AIDS. The comorbidities for which US is useful include tumors, infections and vascular pathology resulting from abnormal fat metabolism and inflammatory and degenerative changes. US has proven useful for diagnosis, image-guided interventional procedures, follow-up of patients on specific treatment regimens and screening for early detection of comorbidities. This review article outlines these applications.

Tumors

Tumors affecting HIV patients are divided into AIDS-defining cancers (ADC) and non-ADC. ADC are: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and cervical cancer. Non- ADC include several cancers such as lung and breast cancer. Benign neoplasms also manifest as comorbidities in HIV/AIDS. Common benign neoplasms include liver hemangiomas, and lipomas in different parts of the body. In the USA, the incidence of ADC (NHL and KS) stood at 3.5/1000 person-years in 2005, and the proportion of cancers in HIV/AIDS contributed to by ADC was 25.9% in the same year [1].

■NHL & Hodgkin’s lymphoma

NHL is the most prevalent comorbid tumor in HIV/AIDS. In the USA, there has been a decrease in NHL between 1996 and 2005 from >5/1000 to 1/1000 person-years [1,2].

HIV/AIDS-associated NHL is often of a high grade and with a poor prognosis. Common histological types are lymphoblastic, immunoblastic and Burkitt’s. NHL is often multifocal, involving several organs in the abdomen. In the liver, it may be solitary or multiple and is usually hypoechoic or anechoic, but may also be hyperechoic and, at times, with a target sign [3].

In the spleen, NHL may manifest as splenomegaly with or without focal masses. The masses are usually hypoechoic or anechoic [3,4].

In the kidney, NHL takes on different appearances depending on its location and multiplicity. It may manifest as generalized kidney enlargement or as solitary or multiple parenchymal masses, displacing vessels. The masses may be hypoechoic or anechoic and may not show a malignant pattern of vascularity with Doppler testing. This malignant pattern is characterized by an increase in the number of vessels. These numerous vessels also appear abnormally tortuous and haphazardly distributed. NHL may show subcapsular, perirenal and pararenal extensions [5]. Bowel involvement may be seen as thickening, loss of the normal five-layer structure or hypervascularity on a color Doppler [3,6]. Ovarian involvement in NHL may show as hyperechogenic masses, which may be bilateral [7]. In the testis, NHL may manifest as mixed echogenicity, predominantly hypoechoic mass, with increased flow at Doppler [8].

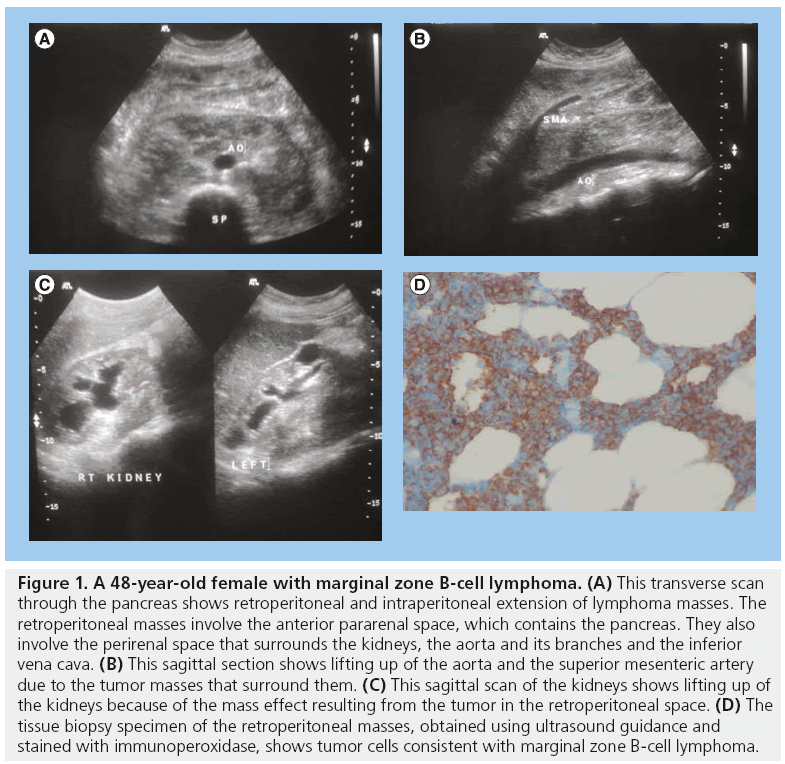

Lymph node involvement in NHL is common. Retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal nodes may be involved. They may be isoechoic or hypoechoic with the surrounding structures. Rarely the lymph nodes may show areas of calcification [3]. Uniform thickening of major abdominal and hepatic vessels due to NHL infiltration has been observed [3]. NHL may extensively extend into the pararenal and perirenal spaces of the abdomen and retroperitoneum, surrounding the major arteries, pancreas and kidney (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A 48-year-old female with marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. (A) This transverse scan through the pancreas shows retroperitoneal and intraperitoneal extension of lymphoma masses. The retroperitoneal masses involve the anterior pararenal space, which contains the pancreas. They also involve the perirenal space that surrounds the kidneys, the aorta and its branches and the inferior vena cava. (B) This sagittal section shows lifting up of the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery due to the tumor masses that surround them. (C) This sagittal scan of the kidneys shows lifting up of the kidneys because of the mass effect resulting from the tumor in the retroperitoneal space. (D) The tissue biopsy specimen of the retroperitoneal masses, obtained using ultrasound guidance and stained with immunoperoxidase, shows tumor cells consistent with marginal zone B-cell lymphoma.

The incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in HIV patients on HAART in one study in the USA was 0.65%. This may manifest as multiple abdominal lymphadenopathy [9].

■Kaposi sarcoma

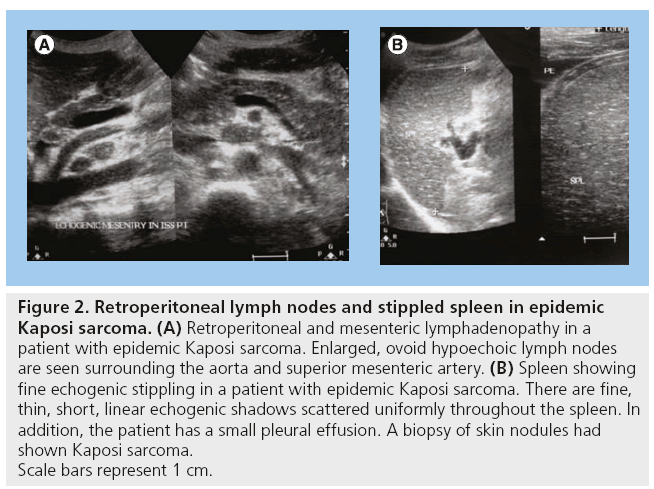

KS is one of the most common malignancies of the abdomen in HIV/AIDS patients. In the USA, there has been a decrease in KS between 1996 and 2005 from 5/1000 to 1/1000 personyears [1,2]. KS may involve the GI tract and other abdominal and retroperitoneal structures. The most common gastrointestinal sites are the small intestines, colon and stomach [10,11]. In the liver, KS may manifest as hepatomegaly or focal hyperechoic masses, which may be adjacent to the portal triad [12]. In the genitourinary system, there may be hydronephrosis, with or without hydroureter. Retroperitoneal masses encasing the aorta and ureters leading to hydronephrosis have been observed. The lymph node enlargement in KS cannot be distinguished from tuberculosis (TB) just by US (Figure 2) [3].

Figure 2: Retroperitoneal lymph nodes and stippled spleen in epidemic

Kaposi sarcoma. (A) Retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymphadenopathy in a

patient with epidemic Kaposi sarcoma. Enlarged, ovoid hypoechoic lymph nodes

are seen surrounding the aorta and superior mesenteric artery. (B) Spleen showing

fine echogenic stippling in a patient with epidemic Kaposi sarcoma. There are fine,

thin, short, linear echogenic shadows scattered uniformly throughout the spleen. In

addition, the patient has a small pleural effusion. A biopsy of skin nodules had

shown Kaposi sarcoma.

Scale bars represent 1 cm.

■Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma has been noted as a comorbidity in HIV/AIDS and its incidence is rising, especially in the context of hepatitis C and B virus coinfections. The reason for the increase is postulated to be either acceleration of hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis by the HIV virus or the increased longevity of HIV/AIDS patients due to HAART, but there is no proof for either. Hepatocellular carcinoma may be solitary or multiple and with varying grades of echogenicity [3,4,13].

■Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma has also been documented in HIV/AIDS patients, and at times in association with AIDS-related cholangitis, but it is not yet proven if its incidence is more than in the seronegative population [14].

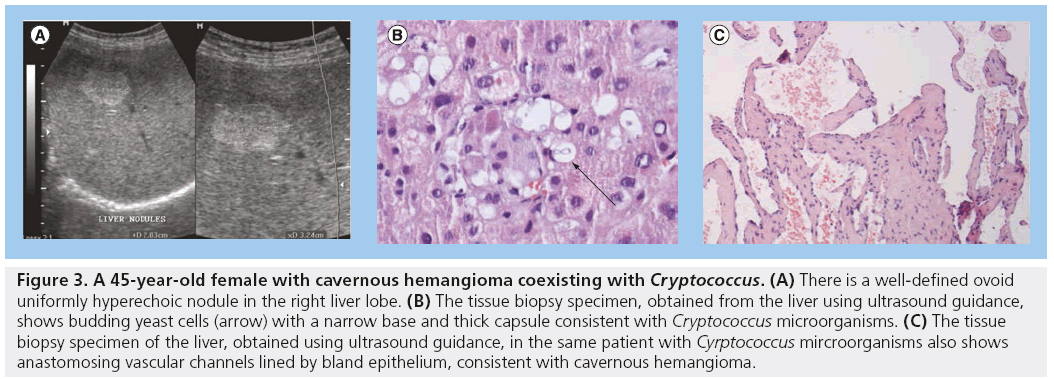

■Hemangiomas

The most frequent histopathological diagnosis for solitary echogenic liver masses in HIV/AIDS patients in Uganda is carvenous hemangioma. In one patient, a coexistence of hemangioma and Cryptococcus microorganisms was documented (Figure 3) [3].

Figure 3: A 45-year-old female with cavernous hemangioma coexisting with Cryptococcus. (A) There is a well-defined ovoid uniformly hyperechoic nodule in the right liver lobe. (B) The tissue biopsy specimen, obtained from the liver using ultrasound guidance, shows budding yeast cells (arrow) with a narrow base and thick capsule consistent with Cryptococcus microorganisms. (C) The tissue biopsy specimen of the liver, obtained using ultrasound guidance, in the same patient with Cyrptococcus mircroorganisms also shows anastomosing vascular channels lined by bland epithelium, consistent with cavernous hemangioma.

Lipomas have been described, especially in patients on HAART treatment. These lipomas may be in subcutaneous tissues of the abdomen. The lipomas usually appear as echogenic masses [15].

Tuberculosis

AIDS remains the strongest risk factor for developing abdominal TB. The incidence of TB among patients varies with CD4 count or WHO stage, and with HAART treatment. In South Africa in 2005, the risk of TB in patients with CD4 of <100 ml and with WHO stages 3–4 was 5.7 and 3.88/100 person-years, respectively [16]. The impaired Th1-type immune response makes HIV/AIDS patients more susceptible to abdominal TB. Abdominal TB prevalence in HIV/AIDS varies depending on the geographical location and the patient’s immunity as per CD4 count [17]. The sonographic appearance of

TB is not pathognomonic, and biopsy with histology and/or staining for acid-fast bacilli is the only method of proof [3,18].

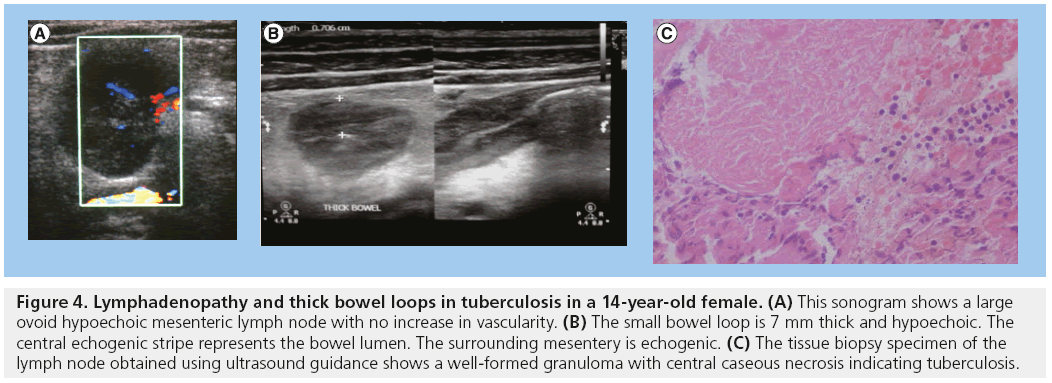

In most studies, the most common sonographic observation in 55.3–96.7% of patients is lymphadenopathy. This may be retroperitoneal and/or mesenteric. The size of lymph nodes varies, but they are commonly hypoechoic or anechoic and avascular, at times with loss of central hilar echogenicity. Sometimes the nodes may coalesce. Aspiration of nodes commonly shows caseation, granulomas and plenty of acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4) [3,18–24].

Figure 4: Lymphadenopathy and thick bowel loops in tuberculosis in a 14-year-old female. (A) This sonogram shows a large ovoid hypoechoic mesenteric lymph node with no increase in vascularity. (B) The small bowel loop is 7 mm thick and hypoechoic. The central echogenic stripe represents the bowel lumen. The surrounding mesentery is echogenic. (C) The tissue biopsy specimen of the lymph node obtained using ultrasound guidance shows a well-formed granuloma with central caseous necrosis indicating tuberculosis.

In one study in India, among non-AIDS patients with abdominal TB, ascites were more common (79%) compared with lymphadenopathy (39%) and in this study, US proved to be more useful in comparison with other imaging modalities for the investigation of TB abdomen [25].

Apart from Mycobacteria tuberculosis, other mycobacteria have been documented in some cases of lymphadenopathy.

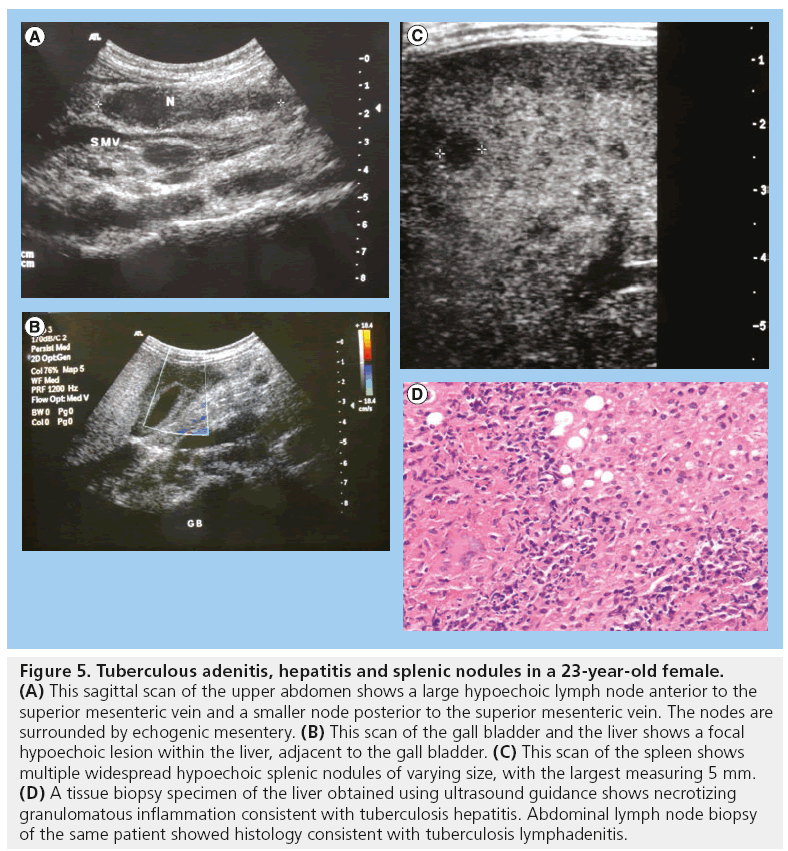

The commonest splenic appearance in abdominal TB is multiple small hypoechoic splenic nodules of size 0.1–1 cm (Figure 5). These are seen in 7.1–89.7% of patients with TB abdomen, and thus high-resolution US is necessary to clearly show these small nodules. Splenomegaly is encountered in 12.9–27.6% of patients with abdominal TB. The spleen may also show small hypoechoic nodules or areas of necrosis [3,20,26,27]. Mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis may also give small hypoechoic splenic nodules.

Figure 5: Tuberculous adenitis, hepatitis and splenic nodules in a 23-year-old female. (A) This sagittal scan of the upper abdomen shows a large hypoechoic lymph node anterior to the superior mesenteric vein and a smaller node posterior to the superior mesenteric vein. The nodes are surrounded by echogenic mesentery. (B) This scan of the gall bladder and the liver shows a focal hypoechoic lesion within the liver, adjacent to the gall bladder. (C) This scan of the spleen shows multiple widespread hypoechoic splenic nodules of varying size, with the largest measuring 5 mm. (D) A tissue biopsy specimen of the liver obtained using ultrasound guidance shows necrotizing granulomatous inflammation consistent with tuberculosis hepatitis. Abdominal lymph node biopsy of the same patient showed histology consistent with tuberculosis lymphadenitis.

The most common liver finding in abdominal TB is hepatomegaly (18.8–20.08%). Other findings are increases in liver echogenicity and hyperechoic nodules, larger hepatic masses or granulomas, and periportal hypoechoic masses coexisting with scattered foci of calcifications (Figure 5) [3,4,20,28].

Ascites are a common manifestation of abdominal TB, and may be seen in 2.9–76% of TB patients. The ascites may be free or loculated, and may have septations. Ascites may also give a lattice-like pattern, and may show small particles or incomplete septa resembling violin strings [3,17,19,20,22,29,30].

Renal involvement in abdominal TB may manifest as multiple hypoechoic lesions, small cortical thick-walled abscesses or small calcified foci in longstanding infections. Hydronephrosis due to obstruction by retroperitoneal masses has been observed and this may resolve with TB therapy. The adrenal glands and urinary bladder wall may also show small hypoechoic nodules [5,26].

Bowel involvement is frequently observed in abdominal TB. The small bowel is most commonly involved, but the stomach, duodenum, jejunum and colon are also involved. The most common portion of the small bowel to be involved is the ileal–cecal junction. The involved bowel is often thickened and the thickening is often uniform, and the wall hypoechoic, with loss of the normal five-layer wall structure, and with no increase in vascularity (Figure 4). The bowel is sometimes matted, and may be associated with intestinal obstruction [3,18,26,31].

Pelvic TB may present with ascites, tuboovarian masses or omental nodules or masses. The sonographic appearance of an ovarian or pelvic mass and ascites may mimic ovarian carcinoma and, furthermore, the carcino–embryonic antigen may also be positive in women with TB pelvis. Laparoscopy and biopsy are necessary for differentiating TB pelvis from ovarian carcinoma [29,32]. The mesentery may be involved in TB abdomen and this may be seen as thickening and hyperechogenicity [23].

Nonspecific adenitis

Nonspecific lymphadenitis is not infrequent in HIV. Some patients may present with significantly large mesenteric or retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy but with no specific histological finding. In some of these patients, the histology report is nonspecific inflammation, nonspecific lymphocyte infiltration with or without background necrosis and cellular debris. US is not able to differentiate nonspecific adenitis from other types of lymphadenopathy which have a specific cause. Special histology stains are necessary to exclude TB and the clinical picture or evidence of TB elsewhere in the body are useful in excluding TB adenitis.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is characterized by the flaring up of already existing comorbid conditions at the onset of HAART treatment. IRIS is due to unregulated restitution of a pathogen-specific immune response. It is observed in 10–25% of patients on HAART [33]. It may occur for a variety of comorbidities, such as M. tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterium, fungi, herpes viruses, cholangiopathy and even tumors. For TB, this may be seen as lymphadenopathy, ascites, splenic nodules and abscesses in different organs. Patients with extrapulmonary TB at initial diagnosis and low lymphocyte counts are more at risk. IRIS may occur from a few weeks to 2 years after initiation of HAART [16,34–38].

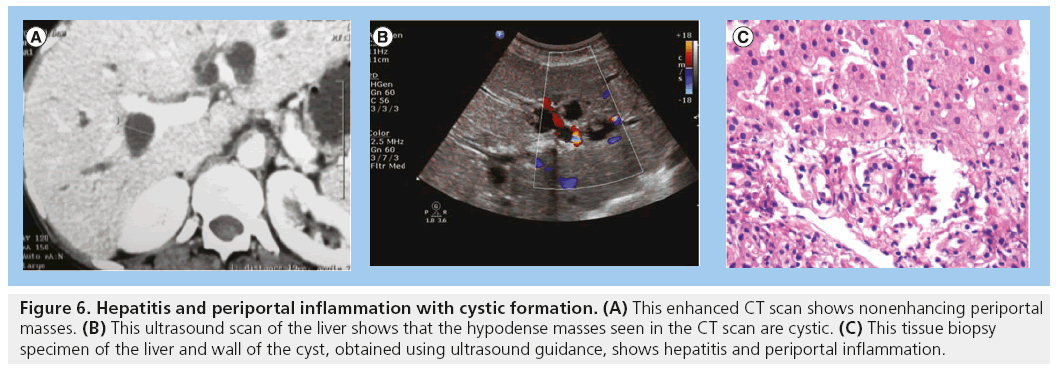

Hepatitis

Hepatitis has been documented as one of the HIV/AIDS comorbidities. The liver may appear normal in size and often shows increased echogenicity. Hepatitis may be viral or TB-related (Figure 5) [3,4]. Irregular thick-walled cystic spaces may accompany the hepatitis (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Hepatitis and periportal inflammation with cystic formation. (A) This enhanced CT scan shows nonenhancing periportal masses. (B) This ultrasound scan of the liver shows that the hypodense masses seen in the CT scan are cystic. (C) This tissue biopsy specimen of the liver and wall of the cyst, obtained using ultrasound guidance, shows hepatitis and periportal inflammation.

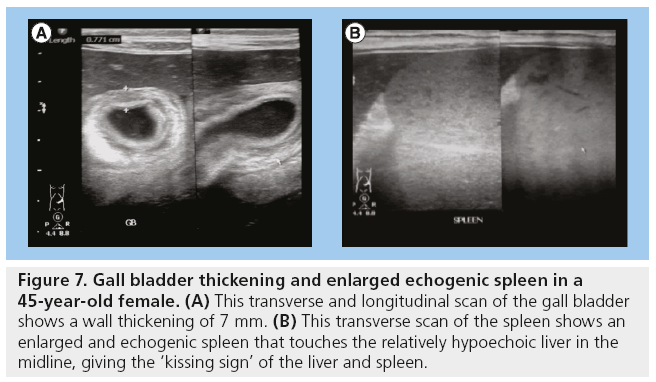

Gall bladder wall thickening & cholangiopathy

Gall bladder wall thickening and HIV-associated cholangiopathy are comorbidities in HIV/AIDS. Gall bladder wall thickening and cholangiopathy often coexist and their pathogenesis is thought to be similar (Figure 7) [3].

Figure 7: Gall bladder thickening and enlarged echogenic spleen in a 45-year-old female. (A) This transverse and longitudinal scan of the gall bladder shows a wall thickening of 7 mm. (B) This transverse scan of the spleen shows an enlarged and echogenic spleen that touches the relatively hypoechoic liver in the midline, giving the ‘kissing sign’ of the liver and spleen.

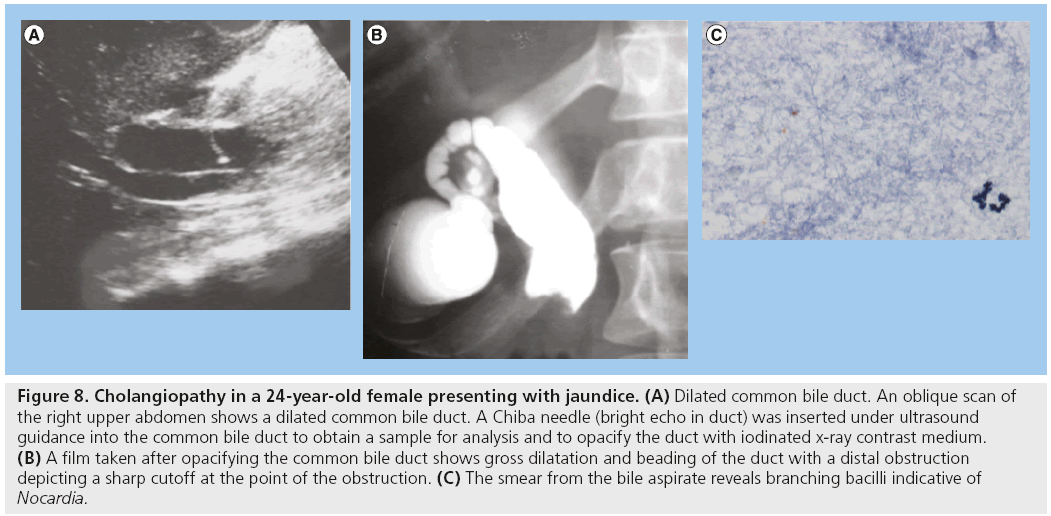

Bile duct abnormalities in HIV/AIDS are observed in 20–49% of patients and the most common is cholangiopathy [3,4,39–41]. Cholangiopathy is seen using US as bile duct thickening, obstruction and dilatation. Various infective agents have been associated with HIV cholangiopathy, namely cryptosporidia, microsporidia, cytomegalo-inclusion virus, mycobateria avium intracellulare and other mycobacteria (Figure 8). Other associated infections are fungus-like Histoplasma capsulatum and viruses. All these have been isolated in the specimens of these patients, but none are yet proven to be the actual causative agent. KS of the billiary ducts may also have been associated with cholangitis [3,42–47]. Patients with cholangiopathy are known to have a poor prognosis, but antiretroviral treatment has improved the prognosis of these patients. Antiparasitic agents against cryptosporidia do not appear to improve prognosis [46,48].

Figure 8: Cholangiopathy in a 24-year-old female presenting with jaundice. (A) Dilated common bile duct. An oblique scan of the right upper abdomen shows a dilated common bile duct. A Chiba needle (bright echo in duct) was inserted under ultrasound guidance into the common bile duct to obtain a sample for analysis and to opacify the duct with iodinated x-ray contrast medium. (B) A film taken after opacifying the common bile duct shows gross dilatation and beading of the duct with a distal obstruction depicting a sharp cutoff at the point of the obstruction. (C) The smear from the bile aspirate reveals branching bacilli indicative of Nocardia.

Pancreatitis

The incidence rate of pancreatitis among HIV-1-infected patients as per one study in the USA in 2006 was 0.61/1000 person-years [49]. Acute and chronic pancreatitis may occur at times with pseudocyst formation. Giant pseudocysts in the pancreas have been documented [3,50]. Some studies have reported an increased incidence of acute pancreatitis for patients in whom hydroxyureas are used to potentiate antiretroviral treatment. The proportion of pancreatitis attributed to antiretroviral treatment in HIV/AIDS patients is uncertain [51]. Pancreatic TB has been documented in patients with immunodeficiency syndrome. It may manifest as well-defined cystic masses, solid masses or pancreatitis. Aspirate of cystic masses is often positive for acid-fast bacilli with Ziehl–Neelsen stain [52,53].

HIV-associated nephropathy & other renal pathologies

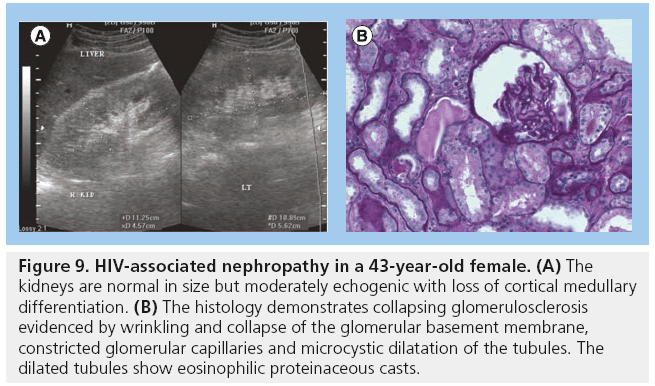

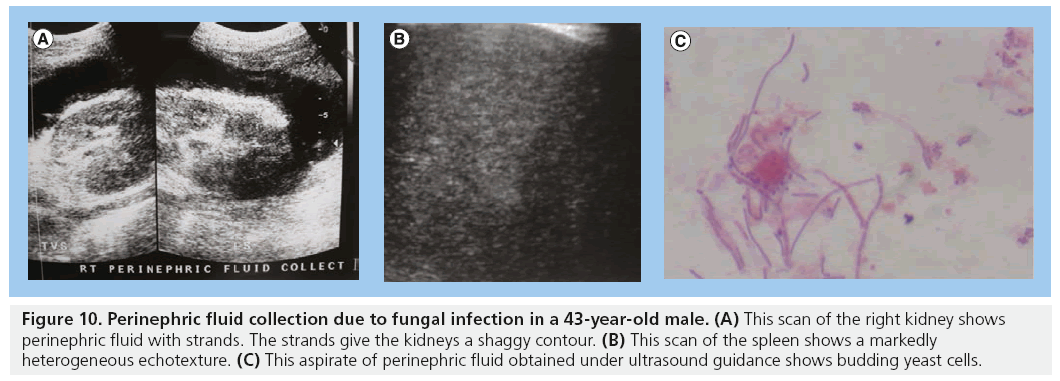

The incidence of HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) among the black population in the USA is 3.5–12% [54]. The most common renal pathology is HIVAN. In the USA, HIVAN has been found to be more prevalent in American men of African origin. This higher prevalence is thought to be genetic and a gene MYH9 is now considered to be a major-effect risk gene for the histopathological changes in HIVAN. HIVAN may present as reduced renal function or renal failure characterized by proteinuria and high creatinine levels. The most common histopathological diagnosis in HIVAN is collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Increased renal echogenicity, equal to or approaching that of the renal sinus fat, has been demonstrated to be statistically significant for HIVAN, occurring in up to 89% of patients. The echogenicity is often associated with loss of corticomedullary differentiation and there may be thick pelvicalyceal system walls. The kidneys in HIVAN are often normal in size but may be enlarged and enlargement is usually globular in the initial stages. HIVAN can only be confirmed by biopsy and histology (Figure 9) [5,55–57]. The perinephric space may be infiltrated by tumor, bacterial or fungal infections (Figure 10).

Figure 9: HIV-associated nephropathy in a 43-year-old female. (A) The kidneys are normal in size but moderately echogenic with loss of cortical medullary differentiation. (B) The histology demonstrates collapsing glomerulosclerosis evidenced by wrinkling and collapse of the glomerular basement membrane, constricted glomerular capillaries and microcystic dilatation of the tubules. The dilated tubules show eosinophilic proteinaceous casts.

Figure 10: Perinephric fluid collection due to fungal infection in a 43-year-old male. (A) This scan of the right kidney shows perinephric fluid with strands. The strands give the kidneys a shaggy contour. (B) This scan of the spleen shows a markedly heterogeneous echotexture. (C) This aspirate of perinephric fluid obtained under ultrasound guidance shows budding yeast cells.

Apart from HIVAN, other pathologies include nephrolithiasis, chronic pyelonephritis, fungal infections (Pneumocystis jiroveci and Candida albicans) and HAART-related nephropathy.

Other HIV/AIDS comorbid infections

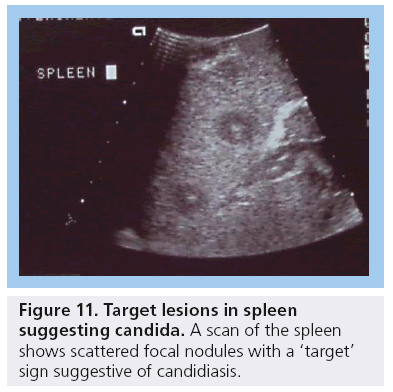

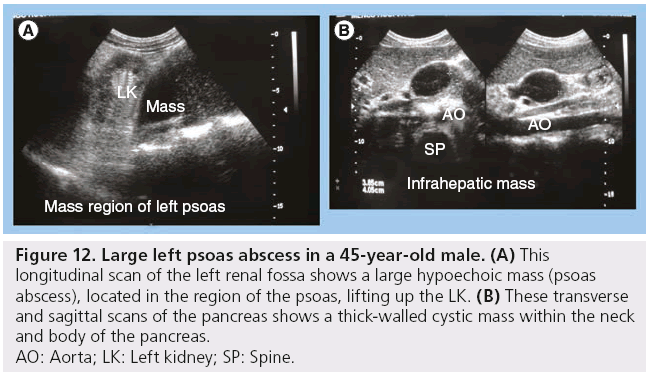

Other infectious HIV comorbidities include pyogenic, fungal and bacterial infections and these may involve all abdominal organs, but more commonly the liver, spleen and kidneys. Candida of the spleen shows as multiple small nodules typically with a target sign (Figure 11) [3,4]. The psoas is the most commonly involved abdominal wall muscle and psoas abscesses have been described (Figure 12) [3].

Figure 12: Large left psoas abscess in a 45-year-old male. (A) This

longitudinal scan of the left renal fossa shows a large hypoechoic mass (psoas

abscess), located in the region of the psoas, lifting up the LK. (B) These transverse

and sagittal scans of the pancreas shows a thick-walled cystic mass within the neck

and body of the pancreas.

AO: Aorta; LK: Left kidney; SP: Spine.

Vascular manifestations

Premature atherosclerosis may occur due to inflammatory action of the HIV virus on the endothelial wall and abnormal fat metabolism. Abnormal fat metabolism is a physiological complication of HIV/AIDS and manifests as high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, especially in patients on HAART. Other vascular complications may be aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms, aortitis, thrombosis and thromboembolism. For patients with pseudoaneurysms, a defect may be visualized in a thickened part of the vessel associated with hyperechoic spotting [58–62].

Conclusion

US is valuable in the assessment of abdominal pathology in HIV/AIDS patients. It is applicable in the evaluation of HIV/AIDS-related tumors, TB, hepatitis, cholangiopathy, pancreatitis, IRIS, nephropathy and vascular system changes. The findings, though not pathognomonic, help in characterizing some of the diseases and in image-guided biopsy procedures. Physicians should exploit this widely available and relatively affordable technology in the management of HIV/AIDS patients with abdominal symptoms.

Future perspective

■Applying results to routine screening before institution of ARVs

It is hoped that nurses, assistant physicians and physicians can be taught basic abdominal US and with the rapidly evolving technology in handheld US scanners they will be able to quickly screen and triage patients with or without pathology, such as TB, which can lead to IRIS.

■Applying tele-US for remote diagnosis of HIV abdominal morbidity

These portable or handheld devices can also be used for tele-US for diagnostic or consultation purposes in cases where US interpretation expertise is lacking.

■Better disease characterization using advances in US technology

With recent advances in US tissue elastography, it is possible that this can be applied to noninvasively distinguish tumors, such as KS and lymphoma, from other masses, such as TB and pyogenic abscesses. This would reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies and increase the yield for positive histology.

Contrast-enhanced US may also aid in localization and characterization, but it is still expensive for developing countries.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

•of interest

• •of considerable interest

- Long LJ, Engels EA, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Incidence and outcomes of malignancy in the HAART era in an urban cohort of HIVinfected individuals. AIDS 22(4), 489–496 (2008).

- Mayor AM, Gomez MA, Rios-Olivares ER, Hunter-Mellado RF. AIDS-defining neoplasm prevalence in a cohort of HIV-infected patient, before and after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ethn. Dis. 18(2 Suppl. 2), 189–194 (2008).

- Kawooya GM, Muyinda Z, Byanyima R, Kiguli-Malwadde E. Abdominal ultrasound findings in HIV patients: a pictorial review. Ultrasound 16(2), 62–72 (2008).

- Tshibwabwa ET, Mwaba P, Bogle-Taylor J, Zumla A. Four-year study of abdominal ultrasound in 900 Central African adults with AIDS referred for diagnostic imaging. Abdom. Imaging 25(3), 290–296 (2000).

- Symeonidou C, Standish R, Sahdev A, Katz RD, Morlese J, Malhotra A. Imaging and histopathologic features of HIV-related renal disease. Radiographics 28(5), 1339–1354 (2008).

- Toma P, Granata C, Rossi A, Garaventa A. Multimodality imaging of Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in children. Radiographics 27(5), 1335–1354 (2007).

- Crawshaw J, Sohaib SA, Wotherspoon A, Shepherd JH. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the ovaries: imaging findings. Br. J. Radiol. 80(956), e155–e158 (2007).

- Surti KM, Ralls PW. Sonographic appearance of plasmablastic lymphoma of the testes. J. Ultrasound Med. 27(6), 965–967 (2008).

- Vichez RA, Finch CJ, Jorgensen JL, Butel JS. The clinical epidemiology of Hodgkins lymphoma in HIV-infected patients in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era. Medicine 82(2), 77–81 (2003).

- Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6(7), 459–462 (2010).

- Hancock S, Pfau PR. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, e463–e464 (2010).

- Restrepo CS, Martinez S, Lemos JA et al. Imaging manifestations of Kaposi sarcoma. Radiographics 26(4), 1169–1185 (2006).

- MacDonald DC, Nelson M, Bower M, Powles T. Hepatocellular carcinoma, human immunodeficiency virus and viral hepatitis in the HAART era. World J. Gastroenterol. 14(11), 1657–1663 (2008).

- Hocqueloux L, Molina JM, Gervais A. Cholangiocarcinoma and AIDS-related sclerosing cholangitis. Ann. Intern. Med. 132(2), 1006–1007 (2000).

- Schambelan M, Benson CA, Carr A et al. Management of metabolic complications associated with antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection: recommendations of an international AIDS society–USA panel. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 31(3), 257–275 (2002).

- Lawn SD, Badri M, Wood R. Tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients receiving HAAR: long term incidence and risk factors in a South African cohort. AIDS 19(18), 2109–2116 (2005).

- Sanai FM, Bzeizi KI. Systematic review: tuberculous peritonitis – presenting features, diagnostic strategies and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 22(8), 685–700 (2005).

- Marjanović H-B, Pecić V, Marjanović G, Marjanović V. Abdominal localisation of tuberculosis and the role of surgery. Med. Biol. 15(2), 51–55 (2008).

- Heller T, Goblirsch S, Wallrauch C, Lessells R, Brunetti E. Abdominal tuberculosis: sonographic diagnosis and treatment response in HIV-positive adults in rural South Africa. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14(6), e108–e112 (2010).

- Patel MN, Beningfield S, Burch V. Abdominal and pericardial ultrasound in suspected extrapulmonary or disseminated tuberculosis. S. Afr. Med. J. 101(1), 39–42 (2011). nn Shows positive statistical correlation of lymphadenopathy and pericardial effusion for the diagnosis of TB by US.

- Sculier D, Vannarith C, Pe R et al. Performance of abdominal ultrasound for diagnosis of tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons living in Cambodia. J. Acquir. Immune Syndr. 55(4), 500–502 (2010).

- Sinkala E, Sylvia G, Isaac Z et al. Clinical and ultrasonographic features of abdominal tuberculosis in HIV positive adults in Zambia. BMC Infect. Dis. 9, 44 (2009).

- Diagnosis of TB was confirmed by smear of the aspirate or by tissue biopsy and histology. This paper outlines a diagnostic algorithm for abdominal TB.

- Jain R, Sawhney S, Bhargava DK, Berry M. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: sonographic findings in patients with early disease. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 165(6), 1391–1395 (1995).

- Monill-Serra JM, Matinez-Noguera A, Montserrat E, Maidue J, Sebate JM. Abdominal ultrasound findings of disseminated tuberculosis in AIDS. J. Clin. Ultrasound 25(1), 1–6 (1997).

- Khan R, Abid S, Jafri W, Abbas Z, Hameed K, Ahmad Z. Diagnostic dilemma of abdominal tuberculosis in non-HIV patients: an ongoing challenge for physicians. World J. Gastroenterol. 12(39), 6371–6375 (2006).

- Agarwal D, Narayan S, Chakravarty J, Sundar S. Ultrasonography for diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis in HIV- infected people. Indian J. Med. Res. 132, 77–80 (2010).

- Porcel-Martin A, Rendon-Unceta P, Bascunana-Quirell A et al. Focal splenic lesions in patients with AIDS: sonographic findings. Abdom. Imaging 23(2), 196–200 (1998).

- Hosaka A, Masak IY, Yamasaki K, Aoki F. Isolated periportal tuberculosis: characteristic findings of clinical imaging. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 12(4), 779–781 (2008).

- Tongsong T, Sukpan S, Wanapirak W, Sirichotiyakul S, Tongprasert F. Sonographic features of female pelvic tuberculous peritonitis. J. Ultrasound Med. 26(1), 77–82 (2007).

- Uygur-Bayramiçli O, Dabak G, Dabak R. A clinical dilemma: abdominal tuberculosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 9(5), 1098–1101 (2003).

- Collado C, Stirnemann J, Ganne N et al. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis: 17 cases collected in 4 hospitals in the northeastern suburb of Paris. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 29(4), 419–424 (2005).

- Wang D, Zhang JJ, Huang HF, Shen K, Cui QC, Xiang Y. Comparison between peritoneal tuberculosis and primary peritoneal carcinoma: a 16-year, single-center experience. Chin. Med. J. 125(18), 3256–3260 (2012).

- Ratnam I, Chiu C, Kandala NB, Easterbrook PJ. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstruction inflammatory syndrome in an ethnically diverse HIV Type 1-infected cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(3), 418–427 (2003).

- Colebunders R, John L, Huyst V, Kambugu A, Scano F, Lynen L. Tuberculosis immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in countries with limited resources. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 10(9), 946–953 (2006).

- Dhasmana DJ, Dheda K, Ravn P, Wilkinson RJ, Meintjes G. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and management. Drugs 68(2), 191–208 (2008).

- Cheng VC, Yam WC, Woo PC et al. Risk factors for development of paradoxical response during antituberculosis therapy in HIV-negative patient. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 22(10), 597–602 (2003).

- Seyler C, Toure S, Messou E, Bonard D, Gabillard D, Anglaret X. Risk factors for active tuberculosis after antiretroviral treatment initiation in Abidjan. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172(1), 123–127 (2005).

- Yannick B, Claude F, Marc G, Valéry L. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome following cryptosporidial cholangitis. AIDS 25(4), 1801–1803 (2011).

- Kawooya MG. The role of ultrasound in the management of abdominal tuberculosis – HIV influence. J. Jpn Radiol. Soc. 56, 113 (1996).

- Kawooya MG, Muyinda Z, Byanyima RB, Busagwa BN. Abdominal sonographic findings in HIV/AIDS patients at Mengo hospital. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 32, 188–189 (2006).

- Smith FJ, Matheison JR, Cooperberg PL. Radiology abdominal sonography in AIDS: detection at US in a large population. Radiology 192(3), 691–695 (1994).

- Gao Y, Chin K, Mishriki YY. AIDS cholangiopathy in an asymptomatic, previously undiagnosed late-stage HIVpositive patient from Kenya. Int. J. Hepatol. 2011, 465895 (2011).

- Daly CA, Padley SP. Sonographic prediction of a normal or abnormal ERCP in suspected AIDS related sclerosing cholangitis. Clin. Radiol. 51(9), 618–621 (1996).

- Bouche H, Housset C, Dumont JL et al. AIDS-related cholangitis: diagnostic features and course in 15 patients. J. Hepatol. 17(1), 34–39 (1993).

- Miller FH, Gore RM, Nemcek AA, Fitzgerald SW. Pancreaticobiliary manifestations of AIDS. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 166(6), 1269–1274 (1996).

- Sharma A, Dugga L, Jain N, Gupta S. AIDS cholangiopathy. J. Indian Acad. Clin. Med. 7(1), 49–52 (2006).

- Kapelusznik L, Arumugam V, Caplivski D, Bottone EJ. Disseminated histoplasmosis presenting as AIDS cholangiopathy. Mycoses 54(3), 262–264 (2011).

- Ko WF, Cello JP, Roger SJ, Lecours A. Prognostic factors for the survival of patients with AIDS cholangiopathy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98(10), 2176–2181 (2003).

- Reisler RB, Murphy RL, Redfield RR, Parker RA. Incidence of pancreatitis in HIV-1-infected individuals enrolled in 20 adult AIDS clinical trials group studies. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 39(2), 159–166 (2005).

- De Socio GV, Vispi M, Fischer MJ, Baldelli F. A giant pancreatic pseudocyst in a patient with HIV infection. J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care (Chic.) 11(4), 227–229 (2012).

- Moore RD, Keruly JC, Chaisson RE. Incidence of pancreatitis in HIV-infected patients receiving nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor drugs. AIDS 15(5), 617–620 (2001).

- Meesiri S. Pancreatic tuberculosis with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a case report and systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 18(7), 720–726 (2012).

- Suárez-Moreno RM, Hernández-Ramírez DA, Madrazo-Navarro M, Salazar-Lozano CR, García-Álvarez KG, Espinoza-Álvarez A. Tuberculosis of the pancreas: an unsuspected cause of abdominal pain and fever. Cir. Cir. 78(4), 346–350 (2010).

- Ross MJ, Klotman PE. Recent progress in HIV-associated nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13(12), 2997–3004 (2002).

- Di Fiori JL, Rodrigue D, Kaptein EM, Ralls PW. Diagnostic sonography of HIVassociated nephropathy: new observations and clinical correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 171(3), 713–716 (1998).

- Pouria S, Neild GH. Renal failure with large echogenic kidneys. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 12(3), 610–611 (1997).

- Atta MG, Longenecker JC, Fine DM. Sonography as a predictor of human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy. J. Ultrasound Med. 23(5), 603–610 (2004).

- Restrepo CS, Ocazionez D, Suri R, Vargas D. Aortitis: imaging spectrum of the infectious and inflammatory conditions of the aorta. Radiographics 31(2), 435–451 (2011).

- Restrepo CS, Diethelm L, Lemos JA et al. Cardiovascular complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Radiographics 26(1), 213–223 (2006).

- Woolgar JD, Ray R, Maharaj K, Robbs JV. Color Doppler and grey scale ultrasound features of HIV-related vascular aneurysms. Br. J. Radiol. 75(899), 884–888 (2002).

- van Leuven SI, Sankatsing RR, Vermeulen JN, Kastelein JJ, Reiss P, Stroes ES. Atherosclerotic vascular disease in HIV: it is not just antiretroviral therapy that hurts the heart! Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2(4), 324–331 (2007).

• • Compares the ultrasound (US) findings in 900 HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals, thus defining the impact of HIV on sonopathology.

• • This study is strong in sample size (120 patients). The authors also attempt to confirm the US results by correlating them with the clinical and laboratory findings. The patients in the study are followed-up to ascertain resolution of the pathology after tuberculosis (TB) treatment.

• The presence of multiple enlarged abdominal lymph nodes increased the post-test probability for TB, thus emphasizing the usefulness of US.

• • Diagnosis of TB was confirmed by smear of the aspirate or by tissue biopsy and histology. This paper outlines a diagnostic algorithm for abdominal TB.

• Out of 278 HIV-positive patients who had US, 22 had focal splenic lesions, and of these, 86% were due to TB, thus illustrating the high likelihood of TB for HIV patients with splenic nodules.

• Strength of this study lies in the statistical correlation of echogenicity of the kidneys to the grade of HIV-associated nephropathy. The images are of good quality and very informative.

• One of the few original articles on Doppler US of HIV-related vascular disease. 61 Triant VA, Grinspoon SK. Vascular dysfunction and cardiovascular complications. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2(4), 299–304 (2007).