Research Article - Interventional Cardiology (2017) Volume 9, Issue 3

Acetylcholine coronary spasm provocation testing: Revaluation in the real clinical practice

- Corresponding Author:

- Shozo Sueda

Department of Cardiology, Ehime Niihama Prefectural Hospital

Hongou 3 choume 1-1, Niihama City, Ehime 7920042, Japan

Tel: +81897436161

Fax: +81897412900

E-mail: EZF03146@nifty.com

Submitted: April 15, 2017; Accepted: May 03, 2017; Published online: May 08, 2017

Abstract

Background: Japanese Circulation Society guidelines for coronary spastic angina recommended the step-by-step bolus administration of acetylcholine (ACh) dose on both coronary arteries (left coronary artery (LCA): 20/50/100 µg, right coronary artery (RCA): 20/50 µg). Our routine practice employed the maximal 80 µg ACh into the RCA and 200 µg ACh into the LCA not to misdiagnose the patients with coronary spasm. At least from five to seven times procedures are necessary during ACh spasm provocation tests. Radiation exposure and the adverse effect of contrast medium is one of the problems. Objectives: We investigated the procedures of the ACh administration on both coronary arteries in the real clinical practice retrospectively. Methods: We analyzed the consecutive 150 patients who had maximal ACh dose of 200 µg into the LCA. We compared clinical issues with and without saving ACh dose. Positive spasm was defined as a transient >90% narrowing and usual chest symptom or ischemic ECG changes. Results: Among 150 patients, 63 patients (42.0%) had positive provoked spasm. Patients with step-by-step ACh dose into the LCA were significantly higher than those with step-by-step ACh dose into the RCA. Saving of ACh 20 µg, 50 µg, and 100 µg into the LCA was observed in 59 patients, 18 patients, and one patient, respectively. Saving of 20 µg ACh and 50 µg ACh into the RCA was found in 98 patients and 60 patients, respectively. Positive spasm frequency was not different between the patients with and without saving ACh procedures. Radiation exposure time/dose and total used amount of contrast medium in saving ACh tests were significantly lower than those in step-by-step ACh tests. No serious irreversible complications were found. Conclusions: We should reconsider the saving ACh spasm provocation tests in the real clinical practice.

Keywords

Acetylcholine spasm provocation test, Incremental dose, Saving, Radiation exposure, Contrast medium

Introduction

As a pharmacological spasm provocation test, Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) guideline for coronary spastic angina recommended that acetylcholine (ACh) was injected in step-by-step bolus dose of 20/50/100 μg into the left coronary artery (LCA) and 20/50 μg into the right coronary artery (RCA) over 20 seconds with at least a 3-minute interval between each injection [1]. Moreover, our routine practice in Ehime Prefectural Niihama Hospital employed the maximal 80 μg ACh into the RCA and maximal 200 μg ACh into the LCA in the real clinical practice to document coronary spasm in the cardiac catheterization laboratory [2,3]. Five times angiography was necessary to complete the ACh spasm provocation testing according to the JCS guidelines, whereas we had seven times angiography in our routine method. Radiation exposure and renal dysfunction due to contrast medium was one of the clinical problems. We sometimes experienced severe complications during ACh spasm provocation tests [4,5]. Pharmacological spasm provocation testing should be performed without irreversible complications. In the clinic, if we could perform the saving ACh spasm provocation tests without complications, we could decrease the adverse effect of radiation exposure and contrast medium. In this article, we investigated the saving ACh spasm provocation tests in the real clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

Study population

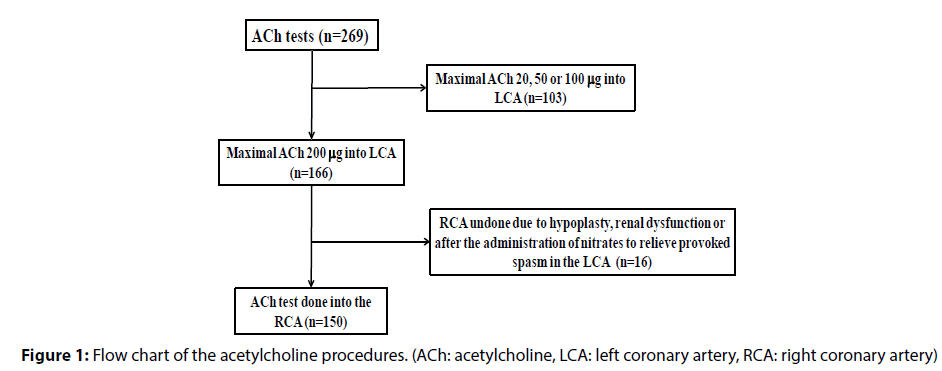

From August 2012 to April 2016, we performed the ACh spasm provocation tests in 269 patients. As shown in Figure 1, among these 269 patients, we performed the maximal ACh dose of 200 μg into the LCA in 166 patients. In 16 patients among 166 patients, we could not perform the ACh tests in the RCA because of hypoplasty, renal dysfunction or after the administration of nitrates to relieve provoked spasm in the LCA. Final study subjects were 150 patients (mean age of 66.9±11.5 years). Male was observed in 108 patients (72.0%). Significant organic stenosis was found in 5 patients (3.3%). Ischemic heart disease was found in 100 patients including 44 patients with rest angina, 9 patients with effort angina, 7 patients with rest and effort angina and 40 patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), while non-ischemic heart disease was recognized in the remaining 50 patients consisting of 18 patients with atypical chest pain, 10 patients with cardiomyopathy and 22 patients with other. A history of smoking was observed in 102 patients (68.0%) and hypertension was recognized in 88 patients (58.7%). Dyslipidemia was also found in 89 patients (59.3%), while diabetes mellitus was observed in 55 patients (36.7%) as shown in Table 1. We also investigated the radiation exposure time (min)/ dose (mGy) and the total used amount of contrast medium in all 150 patients. Among 150 patients, we performed the left ventriculography in 19 patients and percutaneous coronary intervention in 11 patients. Abdominal angiography was performed in 4 patients and elelctrophysiological testing was done in 2 patients.

| Number | 150 |

|---|---|

| Male (%) | 108 (72.0%) |

| Age (year) | 66.9±11.5 |

| Organic stenosis | 5 (3.3%) |

| IHD | 100 (66.7%) |

| Rest angina | 44 (29.3%) |

| Effort angina | 9 (6.0%) |

| Rest & Effort angina | 7 (4.7%) |

| Post PCI | 40 (26.7%) |

| Non-IHD | 50 (33.3%) |

| Smoking | 102 (68.0%) |

| Hypertension | 88 (58.7%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 89 (59.3%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (36.7%) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 185±34 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 132±90 |

| Low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 111±29 |

| High-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 51±13 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dl) | 113±25 |

| Glycohemoglobin (%) | 6.1±0.9 |

| Mean CAG number of ACh testing | 5.2±1.3 |

| Contrast medium (ml) | 142±36 |

| Radiation exposure time (min) | 9.7±5.3 |

| Radiation exposure dose (mGy) | 2256±802 |

Table 1: Patients’ clinical characteristics.

The definition of positive spasm

Positive spasm was defined as ≥90% transient stenosis and usual chest symptoms or ischemic electrocardiogram (ECG) changes. We considered ECG changes to be positive when ST-segment elevation of >0.1 mV and/or ST-segment depression of 0.1 mV were evident 80 msec after the J point in at least two contiguous leads in standard 12-lead ECG during and/ or after the ACh test. We also considered a negative U wave as an ischemic ECG change and positive test result.

Pharmacological spasm provocation test

All drugs except for nitroglycerine were discontinued for >24 hours before the study and nitroglycerine was also discontinued >4 hours before the study. Cardiac catheterization was performed between 9:00 am and 4:00 pm in the fasting state, as previously reported [6-9]. We attempted to perform the pharmacological spasm provocation tests in the morning whenever possible. Before testing baseline coronary arteriograms were obtained of the LCA in the right anterior oblique with caudal projection and of the RCA in the left anterior oblique with cranial projection by injection of 8-10 mL of contrast medium.

Provocation of a coronary artery spasm was performed with an intracoronary injection of ACh, as previously reported [10,11]. ACh chloride (Neucholin-A, 30 mg/2 mL; Zeria Seiyaku, Tokyo, Japan) was injected in incremental doses of 20, 50 100 and 200 μg into the LCA and of 20, 50 and 80 μg into the RCA over 20 seconds with at least a 3-minute interval between each injection. During these periods, the saving ACh spasm provocation tests were recognized as physicians’ own decisions. According to the JCS guidelines, we first performed the ACh spasm provocation tests in the LCA and next in the RCA. Coronary arteriography was performed when ST-segment changes and/or chest pain occurred, or 1-2 minutes after the completion of each injection. When an induced coronary spasm did not resolve spontaneously within 3 minutes after the completion of ACh injections or when hemodynamic instability occurred as the result of coronary spasm, 2.5 to 5.0 mg of nitrate was injected into the involved vessel. A standard 12-lead electrocardiogram was recorded every 30 seconds.

During the study, arterial blood pressure and ECG were continuously monitored on an oscilloscope with Nihon- Kohden polygraphy. In the present study, coronary arteriograms were analyzed separately by 2 independent observers. The percent luminal diameter narrowing of coronary arteries was measured by an automatic edge-counter detection computer analysis system. The size of the coronary catheter was used to calibrate the images in millimeters with the measurement performed in the same projection of coronary angiography at each stage. Focal spasm was defined as a discrete transient vessel narrowing of 90% or more localized in the major coronary artery, whereas diffuse spasm was diagnosed when transient vessel narrowing of 90% or more, compared with baseline coronary angiography, was observed from the proximal to distal segment in the 3 major coronary arteries. Patients with catheter-induced spasms were excluded from this study. Significant organic stenosis was defined as >70 percent luminal narrowing according to the AHA classification [12].

The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the study, and the study protocol complied with the guidelines of the ethical committee at our institution.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as the mean ±1 SD. Clinical characteristics between patients with and without saving procedures were analyzed by the χ2 test with correction. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Incremental procedures

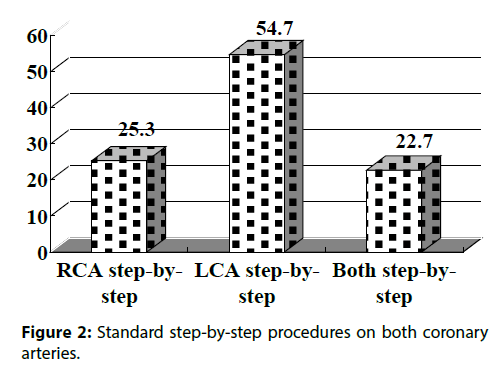

As shown in Figure 2, the step-by-step procedures without saving ACh in the LCA were observed in 54.7% of all patients, whereas those in the RCA were found in 25.3%. As a result, just 34 patients (22.7%) had the step-by-step dose up procedures on both coronary arteries.

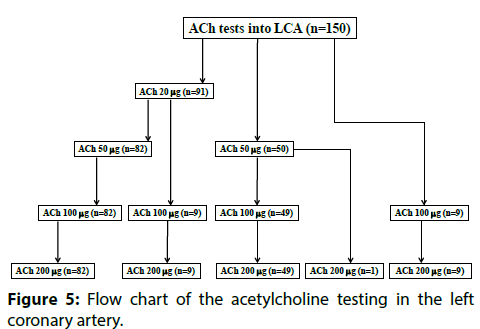

Saving dose of Ach

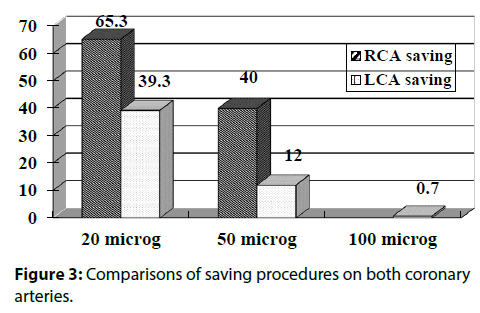

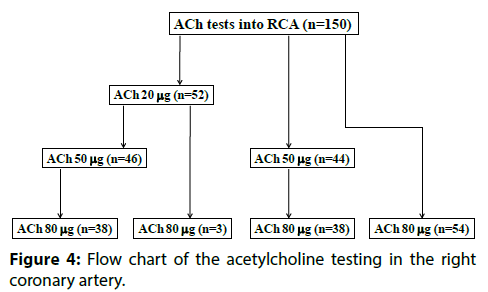

Figure 3 showed that the saving of ACh 20 μg and ACh 50 μg in the RCA were recognized in 98 patients (65.3%) and 60 patients (40%), respectively. In contrast, in the LCA, the saving of ACh 20 μg and ACh 50 μg were observed in 59 patients (39.3%) and 18 patients (12.0%). Only one patient had an ACh 100 μg saving in the LCA. We showed the precise flow chart of ACh procedures in Figure 4 (RCA) & Figure 5 (LCA).

Comparisons of clinical characteristics between the step-by-step and saving ACh procedures in the RCA

As shown in Table 2, positive provoked spasm in patients with and without saving procedures was not different. The mean coronary angiography (CAG) number of ACh testing, the radiation exposure time/ dose and the used amount of contrast medium were significantly higher in patients with step-by-step RCA procedures than in those with saving RCA procedures.

| RCA step-by-step | RCA saving | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| number | 38 (25.3%) | 112 (74.7%) | |

| Male (%) | 29 (76.3%) | 79 (70.5%) | ns |

| Age (year) | 67.8±10.8 | 66.5±11.8 | ns |

| Organic stenosis | 1 (2.6%) | 4 (3.6%) | ns |

| IHD | 20 (52.6%) | 80 (71.4%) | P<0.05 |

| Rest angina | 9 (23.7%) | 35 (31.3%) | ns |

| Effort angina | 1 (2.6%) | 8 (7.1%) | ns |

| Rest & Effort angina | 2 (5.3%) | 5 (4.5%) | ns |

| Post PCI | 8 (21.1%) | 32 (28.6%) | ns |

| Non-IHD | 18 (47.4%) | 32 (28.6%) | P<0.05 |

| Smoking | 27 (71.1%) | 75 (67.0%) | ns |

| Hypertension | 23 (60.5%) | 65 (58.0%) | ns |

| Dyslipidemia | 22 (57.9%) | 67 (59.8%) | ns |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 (39.5%) | 40 (35.7%) | ns |

| Provoked positive spasm | 23 (60.5%) | 64 (57.1%) | ns |

| in the RCA | 17 (44.7%) | 46 (41.1%) | ns |

| in the LCA | 15 (39.5%) | 42 (37.5%) | ns |

| Mean CAG number of ACh testing | 6.9±0.45 | 4.8±0.9 | P<0.01 |

| Contrast medium (ml) | 150±39 | 139±35 | P<0.01 |

| Radiation exposure time (min) | 10.6±5.2 | 9.1±5.5 | P<0.05 |

| Radiation exposure dose (mGy) | 2449±819 | 1931±653 | P<0.01 |

Table 2: Comparisons of clinical characteristics between standard step-by-step and saving procedures in the right coronary artery.

Comparisons of clinical characteristics between step-by-step and saving ACh procedure in the LCA

Table 3 showed that rest angina was significantly higher in LCA incremental procedures than in LCA saving procedures (40.2% vs. 16.2%, p<0.01). In contrast, patients with after PCI was significantly higher in LCA saving procedures than LCA step-by-step procedures (35.3% vs. 19.5%, p<0.05). Although provoked positive spasm was not different between step-by-step and saving ACh procedures (64.6% vs. 50.0%, ns), RCA provoked spasm in patients with LCA step-by-step procedures was significantly higher than that in those with LCA saving procedures (52.4% vs. 29.4%, p<0.01). The radiation exposure time was not different between the two groups, whereas the mean CAG number during the ACh tests, the used amount of contrast medium and radiation exposure dose were significantly lower in patients with LCA saving procedures than in those with LCA step-by-step procedures

| LCA step-by-step | LCA saving | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| number | 82 (54.7%) | 68 (45.3%) | |

| Male (%) | 57 (69.5%) | 51 (75.0%) | ns |

| Age (year) | 66.0±11.4 | 67.9±11.7 | ns |

| Organic stenosis | 2 (2.4%) | 3 (4.4%) | ns |

| IHD | 58 (70.7%) | 42 (61.8%) | ns |

| Rest angina | 33 (40.2%) | 11 (16.2%) | P<0.01 |

| Effort angina | 3 (3.7%) | 6 (8.8%) | ns |

| Rest & Effort angina | 6 (7.3%) | 1 (1.5%) | ns |

| Post PCI | 16 (19.5%) | 24 (35.3%) | P<0.05 |

| Non-IHD | 24 (29.3%) | 26 (38.2%) | ns |

| Smoking | 55 (67.1%) | 47 (69.1%) | ns |

| Hypertension | 52 (63.4%) | 36 (52.9%) | ns |

| Dyslipidemia | 48 (58.5%) | 41 (60.3%) | ns |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29 (35.4%) | 26 (38.2%) | ns |

| Provoked positive spasm | 53 (64.6%) | 34 (50.0%) | ns |

| in the RCA | 43 (52.4%) | 20 (29.4%) | P<0.01 |

| in the LCA | 30 (36.7%) | 27 (39.7%) | ns |

| Mean CAG number of ACh testing | 6.2±0.9 | 4.3±0.8 | P<0.01 |

| Contrast medium (ml) | 151±35 | 129±33 | P<0.01 |

| Radiation exposure time (min) | 9.1±4.3 | 9.9±5.6 | ns |

| Radiation exposure dose (mGy) | 2328±750 | 2154±666 | P<0.01 |

Table 3: Comparisons of clinical characteristics between standard step-by-step and saving procedures in the left coronary artery.

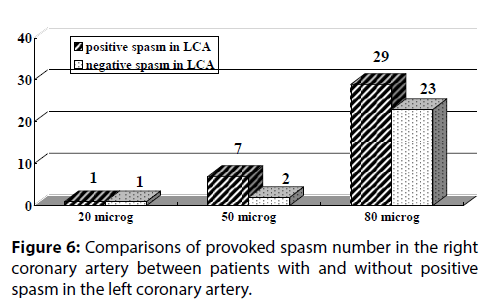

Comparisons of provoked spasm number in the RCA between patients with and without spasm in the LCA

As shown in Figure 6, in patients without positive spasm in the LCA, intracoronary injection of 20 μg, 50 μg and 80 μg ACh into the RCA provoked spasm in one patient, two patients and 23 patients, respectively. Intracoronary administration of 80 μg ACh into the RCA induced positive spasm in 23 (88.5%) of 26 patients. In contrast, in patients with positive spasm in the LCA, intracoronary injection of 20 μg, 50 μg and 80 μg ACh into the RCA disclosed spasm in one patient, 7 patients and 29 patients, respectively. In 29 (78.4%) of 37 patients, intracoronary administration of 80 μg ACh provoked spasm in the RCA.

Figure 6: Comparisons of provoked spasm number in the right coronary artery between patients with and without positive spasm in the left coronary artery.

Complications during ACh spasm provocation tests

No serious irreversible complications were found in all 150 patients during the ACh spasm provocation tests in the LCA. Hypotension was observed in two patients during the ACh spasm provocation tests in the RCA. After the rapid infusions of saline for a few minutes, their blood pressure was gradually returned to baseline level.

Discussion

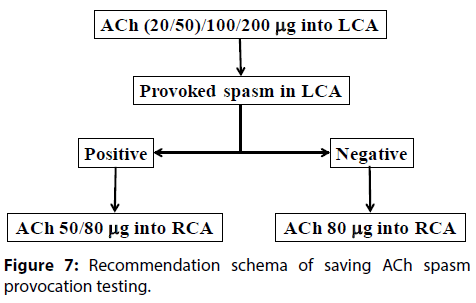

In this article, we reported the real clinical practices of ACh spasm provocation tests. We performed the standard step-by-step ACh spasm provocation testing in just 22.7% patients. Less than half patient had saving procedures in the LCA, whereas third-quarter patients had abridgement procedures in the RCA. We first performed the ACh spasm provocation tests in the LCA and next in the RCA. We may be able to omit the ACh 20 μg or ACh 50 μg procedures in the RCA under the temporary pace maker insertion. We recommend the step-by-step bolus administration of 50 and 80 μg ACh into the RCA in patients with provoked spasm in the LCA and ACh 80 μg single injection into the RCA especially in patients without provoked spasm in the LCA. The radiation exposure time/dose and total used amount of contrast medium were lower in patients with saving procedures than in those with standard step-by-step procedures.

Necessity of saving ACh procedure

Pharmacological spasm provocation tests should be performed in the clinic without irreversible complications. Step-by-step procedures of ACh spasm provocation tests were not always necessary for all patients. We should make an arrangement of standard step-by-step ACh spasm provocation procedure in the clinic. If patients had chronic kidney diseases, we should select the saving procedures not to aggravate the renal dysfunction.

Recommendation for saving ACh spasm provocation tests

As shown in Figure 7, we recommend that the standard step-by-step administration ACh dose of LCA was (20/50), 100 and 200 μg and ACh dose of RCA was 50/80 μg. If patients had provoked positive spasm in the LCA testing, we recommend the step-by-step dose of 50 and 80 μg ACh in the RCA, because intracoronary administration of ACh 20 μg into the RCA provoked spasm in just one (2.7%) of 37 patients. When patients had negative spasm after the LCA testing, we recommend the 80 μg ACh in the RCA, because intracoronary injection of ACh 80 μg into the RCA induced spasm in 23 (88.5%) of 26 patients. However, if patients had been strongly suspected of coronary spasm in the RCA, we should start the ACh 20 μg in the RCA and dose up 50/80 μg when positive spasm was not obtained after the administration of ACh 20 μg.

Implications of saving ACh procedures

Also in the future, we should perform the pharmacological spasm provocation tests without major complications. We also should perform these tests with less burdens for patients and as much as possible for short time. Saving ACh procedures for cardiologists are important knowledge. In the cardiac catheterization laboratory, cardiologists should make an effort to lessen the excessive radiation exposure time/dose and the excessive use of contrast medium.

Limitation of this study

This was a retrospective study and sample size was too small. Our study subjects were just 150 patients who had all ACh 200 μg into the LCA. The second limitation was that just ACh spasm provocation tests were performed in 114 patients (76%) and the remaining 36 patients (24%) had the optional procedures. Radiation exposure time/dose and total used amount of contrast medium in our study was higher than the single ACh spasm provocation test. Further study is necessary to investigate the saving ACh spasm provocation procedures.

Conclusion

In the real clinical practice, we performed the standard step-by-step ACh spasm provocation tests in just 22.7% of patients. The radiation exposure time and dose were lower in patients with saving procedures than in those with standard step-by-step procedures as well as total used amount of contrast medium. We recommend the saving RCA procedures (ACh 50/80 or ACh 80 μg) because of the decrease of radiation exposure time/dose and used amount of contrast medium.

References

- JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment for patients with vasospastic angina (coronary spastic angina) (JCS 2013): Digest version. Circ. J. 74: 2779-2801 (2014).

- Sueda S, Kohno H, Miyoshi T, Sakaue T, Sasaki Y, Habara H. Maximal acetylcholine dose of 200 µg into the left coronary artery as a spasm provocation test: comparison with 100 µg of acetylcholine. Heart. Vessels. 30: 771-778 (2015).

- Sueda S, Mineoi K, Kondo T, et al. Absence of induced spasm by intracoronary injection of 50 µg acetylcholine in the right coronary artery: usefulness of 80 µg of acetylcholine as a spasm provocation test. J. Cardiol. 32: 155-161 (1998).

- Sueda S, Saeki H, Otani T, et al. Major complications during spasm provocation tests with an intracoronary injection of acetylcholine. Am. J. Cardiol. 85: 391-394 (2000).

- Sueda S, Kohno H. Overview of complications during pharmacological spasm provocation tests. J. Cardiol. 68: 1-6 (2016).

- Sueda S, Ochi N, Kawada H, et al. Frequency of provoked coronary vasospasm in patients undergoing coronary arteriography with spasm provocation test of acetylcholine. Am. J. Cardiol. 83: 1186-1190 (1999).

- Sueda S, Kohno H, Fukuda H, et al. Clinical impact of selective spasm provocation tests: comparisons between acetylcholine and ergonovine in 1508 examinations. Coron. Artery. Dis. 15: 491-497 (2004).

- Sueda S, Miyoshi T, Sasaki Y, Sakaue T, Habara H, Kohno H. One of six patients with non-ischemic heart disease exhibit provoked coronary spasms: non-ischemic heart disease associated with ischemia? Intern. Med. 54(3): 281-286 (2014).

- Sueda S, Miyoshi T, Sasaki Y, Sakaue T, Habara H, Kohno H. Complications of pharmacological spasm provocation tests. Angiol. 3: 145 (2015).

- Sueda S, Kohno H, Ochi T, Uraoka T. Overview of the acetylcholine spasm provocation test. Clin. Cardiol. 38: 430-438 (2015).

- Sueda S, Fukuda H, Watanabe K, et al. Clinical characteristics and possible mechanism of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation induced by intracoronary injection of acetylcholine. Am. J. Cardio. 88: 570-573 (2001).

- Scanlon PJ, Faxon DP, Audet AM, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary angiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Coronary Angiography). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 33: 1756-1824 (1999).