Research Article - Neuropsychiatry (2018) Volume 8, Issue 4

Anti-Dementia Drugs and Risk of Cardiovascular Events-A Nationwide Cohort Study in Taiwan

- Corresponding Author:

- Nian-Sheng Tzeng, MD

Assistant Professor, Attending Psychiatrist

Director of Community Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry, Tri-Service General Hospital

National Defense Medical Center, 325, Chung-Gung Rd

Sec 2, Nei-Hu District 114, Tapei, Taiwan, ROC

Tel: +886-2-87927299, +886-2-87923311, ext-13674 or 17484

Abstract

Objectives

Previous studies have reported that anti-dementia drugs could be associated with a lower risk of heart diseases and death. This retrospective cohort study is to investigate the association between the long-term effects of the anti-dementia drugs (ADD) usage and the cardiovascular adverse events (CVE’s).

Methods

Subjects were conducted from January 1, 2000, through December 31, 2013, using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). We enrolled a total of 45,020 subjects, and identified 22,510 patients with ADD usage and randomly selected the propensity scorematched controls without ADD usage in a ratio of 1:1. The Fine and Gray’s survival analysis was used to evaluate the risk of developing CVE in the ADD usage cohort.

Results

A risk reduction of angina pectoris in an ADD usage cohort was found: crude hazard ratio (HR)=0.705 (95% CI: 0.631-0.788, p<0.001) and adjusted HR=0.766 (95% CI: 0.683—0.858, p<0.001), in the 13 years of follow up. However, only the short-term, within one year, associations between the individual cholinesterase inhibitors usage and a lower risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, without the same effects of long-term follow up. No association between the ADD usage and the lower risk of death.

Conclusion

The usage of the ADD was associated with a decreased risk of angina pectoris, but not other CVE’s such as myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, or death, in such a long-term follow up study.

Keywords

Anti-dementia drugs, National health insurance Research database, Cardiovascular adverse events, Cohort study

Introduction

Dementia of Alzheimer type, or Alzheimer dementia (AD), is the most prevalent cause of dementia, with a progressive neurodegenerative disorder which gradually impairs the patient’s cognitive and self-care function and eventually causes death [1,2]. The incidence of the disease doubles every five years in those aged over 65 years [3], and the prevalence of AD is around 2%- 5% in the elderly [4-6]. For the family members and caregivers of patients with AD, it is therefore considered as a heavy burden to the caregivers and the society of these patients [7-10]. Anti-dementia drugs (ADD), including acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) and memantine, could be used in the patients with AD to improve their cognitive functions. AChEI, such as donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine are efficacious and safe for mild to moderate AD [11,12]. Donepezil and memantine are also effective in treating moderate-severe to severe AD [13].

Previous studies have shown that AChEI usage was associated with a decreased risk of mortality and myocardial infarction, with a mean interval of usage of 1-2 years: A Swedish study has shown that AChEI usage, with a mean interval of ADD usage of 495 days, was associated with a reduced risk of MI and death in a nationwide cohort of subjects diagnosed with AD [14], and another Taiwan study found that an AD cohort with a usage of AChEI of two to three years was associated with a lower risk of mortality in comparison to the cohort with AChEI usage shorter than one year [15]. Furthermore, a study on AChEI reported that the usage of AChEI was associated with a decreased risk of ischemic stroke [16]. However, a study in a Danish cohort reported that the memantine treatment was associated with fatal outcomes and other cardiovascular events, which might well result from the selection of more ailing individuals for memantine therapy [17]. We thus hypothesize that ADD usage has been effective in the reduced risk of CVE’s, including angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and over-all mortality, and these effects might well change in the long term follow up after the ADD usage has been discontinued. Therefore, we conducted this population-based, cohort study to examine the associations between ADD, CVE’s, and mortality.

Methods

▪ Data sources

In this study, we used the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID), a subset of two million randomly sampled patients from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan, over a 13-year period (2000-2013). In 1995, the National Health Insurance (NHI) Program was launched in Taiwan, and had contracts with 97% of the medical providers and enrolled more than 99% of the 23 million populations as of June 2009 [18]. The details of the program have been documented in previous studies [10,19-23]. The diagnostic codes used in the NHIRD follow the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) [24].

The treatment for dementia with ADD, either AChEI or memantine, is covered by the NHI, but with strict payment regulations since 2000. Subjects using ADD must be the patients of confirmed AD after complete case studies of clinical symptoms and signs, blood tests, cognitive tests, and neuro-image work-ups. Each diagnosis of AD was made by a board-certified psychiatrist or neurologist, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV), and its Text-revised edition (DSM-IV-TR), or the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorder Association (NINDS-ADRDA), with a history of dementia for more than six months. The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score must be between 10 and 26 and a clinical dementia rating (CDR) grade of either 1 or 2, while memantine and donepezil as an exception for patients, who were ambulatory, with severe AD of MMSE as 5-10 with a CDR grade of 3 [25-27]. The requested blood tests include venereal disease research laboratory, thyroid function, complete blood count, fasting sugar, glutamic–oxaloacetic transaminase, glutamic– pyruvic transaminase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum cobalamin, and folic acid levels. Aside from the clinical presentation, cognition tests, and blood tests, all of the patients must have neuro-image studies, with either a brain computerized tomography or a magnetic resonance image. Patients with old vascular insults, hydrocephalus, brain tumor, or any other potential cause of dementia other than AD noted in these neuro-images were excluded. The diagnostic work-up must be performed and confirmed by a certificated neurologist or psychiatrist [15,25,28]. The NHI Administration hires external experts to review the records of the ambulatory care visits, and the in-patient claims to verify the accuracy of the diagnoses [28]. Therefore, it is suitable to use the NHIRD to examine the association between ASD usage and the potential attenuation of the risk of CVE’s in a long term follow up.

▪ Study design and sampled participants

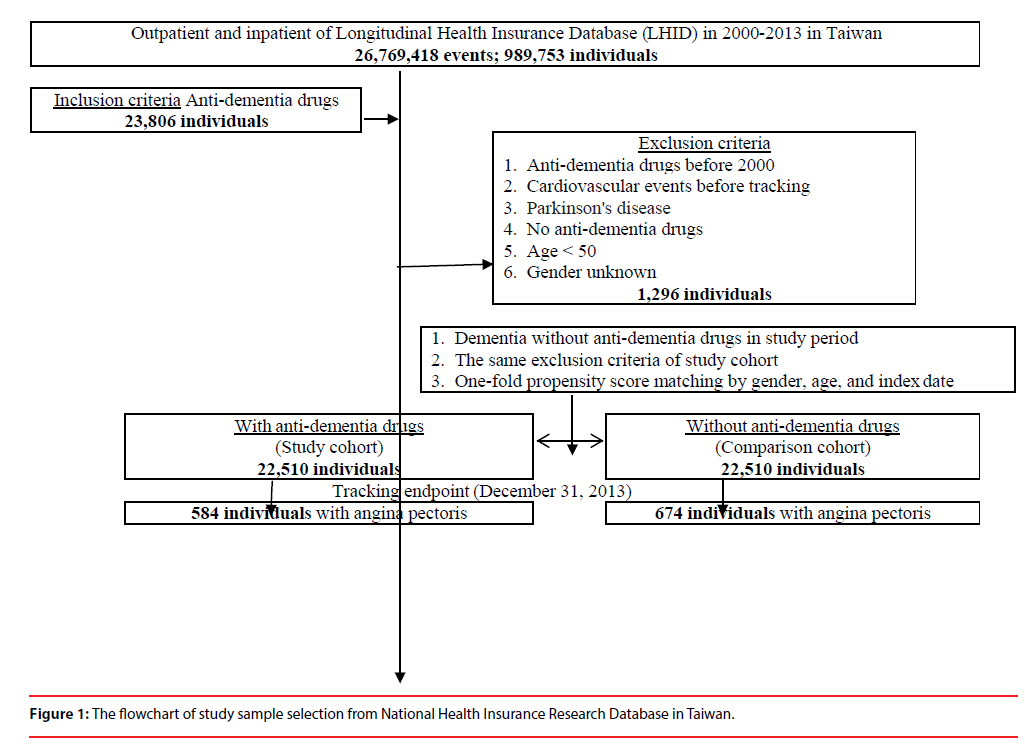

This study was of a retrospective propensity score-matched cohort design, by age, gender, and comorbidity. The inclusion criteria of patients with AD using ADD were patients, as aforementioned in the Data sources, who first started to use ADD between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2013, were identified. This cohort of ADD usage was the propensity matched with a comparison cohort, which consisted of the AD patients who had never been treated with ADD, randomly sampled from the remaining subjects of the LHID data set, and matched (1:1) on the basis of the propensity score, including age, gender, index year, comorbidities. The exclusion criteria were patients using ADD before 2000, those diagnosed with dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and CVE’s before 2000, and those aged <50 years. For the control group of AD without ADD treatment, they were required to have made at least three outpatient visits within one-year of the study period for AD according to these ICD-9-CM codes of 290 (excluding 290.4), and 331.0. In addition, several Taiwan studies have demonstrated the high accuracy and validity of the diagnoses in the NHIRD (Figure 1) [29-31].

Figure 1: The flowchart of study sample selection from National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan.

▪ Covariates

Covariates included gender, age group (50-64, ≥ 65), geographical area of residence (northern, central, southern, and eastern Taiwan), seasons, urbanization level (levels 1 to 4 as described below), level of hospitals, and monthly insured premiums (in New Taiwan dollars (NT$): <18,000, 18,000-34,999 ≥ 35,000). The urbanization of a patients’ residence was defined by the population and indicators of the area’s level of development. Level 1 urbanization was defined as a population >1,250,000 people and a specific status of political, economic, cultural, and metropolitan development. Level 2 was defined as a population between 500,000, and 1,250,000, and an important role in Taiwan’s political system, economy, and culture. Urbanization levels 3 and 4 were defined as having a population between 150,000 and 500,000, and less than 150,000, respectively. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) is the one that is most widely used [32,33]. There are 22 conditions in the CCI [34], and three of these conditions are risk factors for AD: diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and hemiplegia (stroke) [35]. Comorbidities were assessed using the CCI, which categorizes the comorbidities using the ICD- 9-CM codes, scores each comorbidity category, and combines all the scores to calculate a single comorbidity score. A score of zero indicates that no comorbidities were found, and higher scores indicate higher comorbidity burdens [36]. The usage of anti-diabetic medications, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihypertensive drugs, and benzodiazepines were also recorded as covariates. The data of the defined daily dosage (DDD) were obtained from the WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology [37], and the duration of the usage of ADD medications was calculated by dividing the cumulative doses by the DDD of the AChEI or memantine.

For the analysis of the angina pectoris, the risk factors of a coronary artery disease, such as diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM 250), hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401.1, 401.9, 402.10, 402.90, 404.10, 404.90, 405.1, 405.9), and hyperlipidaemia (ICD-9-CM 272.X), [38,39], were also recorded.

▪ Outcome measures

All of the study participants were followed from the index date until the onset of CVE’s, death, withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2013. The CVE’s included myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM code: 410), angina pectoris (ICD- 9-CM code: 413), coronary artery disease (CAD, ICD-9-CM code 410-414), ischemic stroke (ICD- 9-CM code: 434.91), and all-cause mortality. The diagnosis of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, CAD, and ischemic stroket was required to have made at least three outpatient visits within the 1-year study period according to these ICD-9-CM codes, similar to the ways in defining diagnosis in previous studies [19-23].

▪ Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SPSS software version 22.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). χ2 and t tests were used to evaluate the distributions of the categorical and continuous variables between the patients who did and did not use ADD. The Fisher exact test for categorical variables was used to statistically examine the differences between the two cohorts. Fine and Gray’s survival analysis was used to determine the risk of dementia, and the results were presented as a hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Differences in the risk of dementia between the two groups were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. A 2-tailed p value< 0.05 was statistically significant.

▪ Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). The Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital approved this study and waived the need for individual written informed consent (IRB No. 1-104-05-145).

Results

▪ Sample characteristics

A total of 22,510 patients who used ADD were enrolled, and another 1:1 ratio, propensity score matched control group of 22,510 patients without the use of ADD were enrolled. In the baseline characteristics in the matched cohorts as shown in Table 1, there were only marginal differences in comorbidity, location and urbanization level of residence, and medical care level, in the baseline variables between the subjects using and not using ADD, as expected after the propensity scorematching. The study cohort consisted of 45,020 patients with a mean age of 72.96 ± 7.42 (range 65.54–90.38) years at the baseline.

| Anti-dementia drugs | With | Without | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 22,510 | 50.00 | 22,510 | 50.00 | |

| Sex | 0.999 | ||||

| Male | 11,897 | 52.85 | 11,897 | 52.85 | |

| Female | 10,613 | 47.15 | 10,613 | 47.15 | |

| Age (years) | 72.91 ± 7.30 | 73.01 ± 7.54 | 0.152 | ||

| Age group (years) | 0.999 | ||||

| 50-64 | 1,265 | 5.62 | 1,265 | 5.62 | |

| =65 | 21,245 | 94.38 | 21,245 | 94.38 | |

| Insured premium (NT$) | 0.117 | ||||

| < 18,000 | 18,875 | 83.85 | 18,779 | 83.43 | |

| 18,000-34,999 | 2,268 | 10.08 | 2,257 | 10.03 | |

| = 35,000 | 1,367 | 6.07 | 1,474 | 6.55 | |

| CCI_R | 1.90 ± 1.60 | 1.92 ± 1.30 | 0.147 | ||

| Antidiabetic drugs | 0.725 | ||||

| Without | 19,635 | 87.23 | 19,609 | 87.11 | |

| With | 2,875 | 12.77 | 2,901 | 12.89 | |

| Antidepressants | 0.352 | ||||

| Without | 17,198 | 76.40 | 17,113 | 76.02 | |

| With | 5,312 | 23.60 | 5,397 | 23.98 | |

| Antipsychotics | 0.451 | ||||

| Without | 16,393 | 72.83 | 16,465 | 73.15 | |

| With | 6,117 | 27.17 | 6,045 | 26.85 | |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 0.857 | ||||

| Without | 19,999 | 88.84 | 20,012 | 88.90 | |

| With | 2,511 | 11.16 | 2,498 | 11.10 | |

| Benzodiazepines | 0.940 | ||||

| Without | 20,066 | 89.14 | 20,072 | 89.17 | |

| With | 2,444 | 10.86 | 2,438 | 10.83 | |

| Season | 0.127 | ||||

| Spring (March-May) | 5,563 | 24.71 | 5,769 | 25.63 | |

| Summer (June-August) | 5,778 | 25.67 | 5,690 | 25.28 | |

| Autumn (September-November) | 5,617 | 24.95 | 5,498 | 24.42 | |

| Winter (December-February) | 5,552 | 24.66 | 5,553 | 24.67 | |

| Location | < 0.001 | ||||

| Northern Taiwan | 8,290 | 36.83 | 8,052 | 35.77 | |

| Middle Taiwan | 6,987 | 31.04 | 6,763 | 30.04 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 6,085 | 27.03 | 5,341 | 23.73 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 1,095 | 4.86 | 2,221 | 9.87 | |

| Outlets islands | 53 | 0.24 | 133 | 0.59 | |

| Urbanization level | < 0.001 | ||||

| 1 (The highest) | 6,920 | 30.74 | 5,292 | 23.51 | |

| 2 | 9,851 | 43.76 | 9,019 | 40.07 | |

| 3 | 2,309 | 10.26 | 1,964 | 8.73 | |

| 4 (The lowest) | 3,430 | 15.24 | 6,235 | 27.70 | |

| Level of care | <0.001 | ||||

| Medical center | 12,385 | 55.02 | 8,067 | 35.84 | |

| Regional hospital | 8,230 | 36.56 | 9,028 | 40.11 | |

| Local hospital | 1,895 | 8.42 | 5,415 | 24.06 | |

CCI_R: Charlson comorbidity index removed dementia and angina pectoris

Table 1: Characteristics of study at the baseline.

▪ The mean intervals of ADD usage

The mean interval between the first and last time ADD usage was 392.37 (SD=471.24) days, in which the AChEI mean interval was 403.56 (SD=484.77) days, and the memantine was 366.45 (SD=437.26) days (Supplemental Table 1). The mean follow-up years for the ADD usage cohort and non-ADD usage cohort were 11.36 (SD=16.35) and 12.10 (SD=16.58) years, respectively (Supplemental Table 2).

▪ Hazard ratios analysis of ADD effects in the AD patients

Table 2 shows the anti-dementia drugs that were associated with a decreased risk of angina pectoris in the whole follow up period, far longer than the mean interval of the ADD usage. AChEI usage was associated with maxima two years of a lower risk of MI or Ischemic stroke. Memantine usage was only associated with a decreased risk of angina pectoris, but not other CVE’s.

| Events | Angina pectoris | Myocardial infarction | Ischemic stroke | Mortality | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-dementia drugs (With vs. Without) | Competing risk in the model | Competing risk in the model | Competing risk in the model | Non-competing risk in the model | ||||||||||||

| Drug subgroups | Tracking interval (years) | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI |

| Total | Total | 0.761 | 0.679 | 0.853 | < 0.001 | 0.890 | 0.637 | 1.101 | 0.655 | 0.835 | 0.513 | 1.652 | 0.211 | 0.983 | 0.731 | 1.233 |

| = 1 | 0.746 | 0.665 | 0.839 | < 0.001 | 0.820 | 0.618 | 0.972 | 0.039 | 0.811 | 0.501 | 0.933 | 0.020 | 0.914 | 0.708 | 1.099 | |

| > 1, = 3 | 0.773 | 0.690 | 0.871 | 0.002 | 0.888 | 0.632 | 1.004 | 0.265 | 0.840 | 0.514 | 1.025 | 0.136 | 0.988 | 0.722 | 1.145 | |

| > 3, = 5 | 0.825 | 0.733 | 0.935 | 0.016 | 0.899 | 0.701 | 1.020 | 0.362 | 0.924 | 0.618 | 1.140 | 0.224 | 1.021 | 0.808 | 1.196 | |

| > 5, = 10 | 0.888 | 0.762 | 1.001 | 0.051 | 0.951 | 0.728 | 1.289 | 0.430 | 0.967 | 0.665 | 1.542 | 0.388 | 1.104 | 0.844 | 1.498 | |

| > 10 | 0.953 | 0.851 | 1.099 | 0.117 | 0.996 | 0.835 | 1.512 | 0.513 | 1.006 | 0.712 | 2.101 | 0.427 | 1.178 | 0.979 | 1.875 | |

| AChEI | Total | 0.741 | 0.660 | 0.831 | < 0.001 | 0.831 | 0.597 | 1.062 | 0.620 | 0.826 | 0.483 | 1.599 | 0.201 | 0.920 | 0.688 | 1.178 |

| = 1 | 0.726 | 0.646 | 0.817 | < 0.001 | 0.766 | 0.579 | 0.948 | 0.021 | 0.802 | 0.472 | 0.903 | 0.007 | 0.856 | 0.668 | 1.054 | |

| > 1, = 3 | 0.753 | 0.671 | 0.850 | < 0.001 | 0.829 | 0.592 | 1.067 | 0.113 | 0.831 | 0.484 | 0.995 | 0.048 | 0.924 | 0.689 | 1.183 | |

| > 3, = 5 | 0.803 | 0.711 | 0.911 | 0.020 | 0.839 | 0.657 | 1.189 | 0.227 | 0.914 | 0.582 | 1.103 | 0.209 | 0.954 | 0.751 | 1.334 | |

| > 5, = 10 | 0.865 | 0.741 | 0.995 | 0.047 | 0.889 | 0.682 | 1.243 | 0.312 | 0.957 | 0.626 | 1.493 | 0.312 | 1.032 | 0.791 | 1.439 | |

| > 10 | 0.928 | 0.827 | 1.071 | 0.228 | 0.930 | 0.783 | 1.458 | 0.468 | 0.996 | 0.670 | 2.030 | 0.454 | 1.099 | 0.911 | 1.717 | |

| Donepezil | Total | 0.762 | 0.672 | 0.859 | < 0.001 | 0.862 | 0.621 | 1.099 | 0.583 | 0.814 | 0.462 | 1.498 | 0.193 | 0.956 | 0.717 | 1.222 |

| = 1 | 0.747 | 0.655 | 0.845 | 0.001 | 0.795 | 0.602 | 0.970 | 0.020 | 0.791 | 0.451 | 0.849 | 0.006 | 0.889 | 0.695 | 1.098 | |

| > 1, = 3 | 0.774 | 0.683 | 0.879 | 0.008 | 0.860 | 0.611 | 1.002 | 0.053 | 0.819 | 0.463 | 1.029 | 0.298 | 0.960 | 0.704 | 1.146 | |

| > 3, = 5 | 0.826 | 0.724 | 0.946 | 0.031 | 0.874 | 0.686 | 1.018 | 0.120 | 0.901 | 0.557 | 1.044 | 0.372 | 0.981 | 0.793 | 1.191 | |

| > 5, = 10 | 0.891 | 0.753 | 1.031 | 0.113 | 0.921 | 0.712 | 1.287 | 0.243 | 0.945 | 0.599 | 1.398 | 0.498 | 1.073 | 0.812 | 1.501 | |

| >10 | 0.955 | 0.840 | 1.112 | 0.264 | 0.966 | 0.814 | 1.509 | 0.266 | 0.988 | 0.641 | 1.945 | 0.501 | 1.144 | 0.945 | 1.814 | |

| Rivastigmine | Total | 0.721 | 0.641 | 0.819 | < 0.001 | 0.809 | 0.538 | 1.052 | 0.652 | 0.829 | 0.489 | 1.602 | 0.205 | 0.892 | 0.635 | 1.155 |

| = 1 | 0.521 | 0.938 | 0.020 | 0.804 | 0.485 | 0.905 | 0.016 | 0.832 | 0.615 | 1.056 | ||||||

| > 1, = 3 | 0.707 | 0.325 | 0.801 | 0.001 | 0.747 | 1.004 | 0.199 | 0.896 | 0.650 | 1.125 | ||||||

| > 3, = 5 | 0.782 | 0.691 | 0.902 | 0.022 | 0.829 | 0.732 | 0.651 | 0.835 | 0.007 | 0.807 | 1.129 | 0.298 | 0.931 | 0.701 | 1.309 | |

| > 5, = 10 | 0.843 | 0.718 | 0.980 | 0.040 | 0.864 | 0.615 | 1.232 | 0.381 | 0.960 | 0.672 | 1.498 | 0.341 | 1.001 | 0.722 | 1.418 | |

| > 10 | 0.904 | 0.801 | 1.066 | 0.184 | 0.905 | 0.701 | 1.449 | 0.435 | 0.999 | 0.698 | 2.454 | 0.245 | 1.063 | 0.834 | 1.712 | |

| Galantamine | Total | 0.736 | 0.653 | 0.827 | < 0.001 | 0.826 | 0.595 | 1.063 | 0.604 | 0.847 | 0.505 | 1.789 | 0.237 | 0.913 | 0.686 | 1.172 |

| = 1 | 0.722 | 0.631 | 0.819 | < 0.001 | 0.760 | 0.575 | 0.958 | 0.018 | 0.823 | 0.493 | 1.010 | 0.135 | 0.849 | 0.661 | 1.057 | |

| > 1, = 3 | 0.747 | 0.662 | 0.846 | 0.002 | 0.824 | 0.591 | 1.069 | 0.295 | 0.852 | 0.506 | 1.111 | 0.295 | 0.916 | 0.685 | 1.184 | |

| > 3, = 5 | 0.798 | 0.703 | 0.911 | 0.008 | 0.835 | 0.655 | 1.182 | 0.301 | 0.947 | 0.601 | 1.234 | 0.366 | 0.947 | 0.752 | 1.326 | |

| >5, = 10 | 0.860 | 0.731 | 0.999 | 0.049 | 0.885 | 0.680 | 1.295 | 0.425 | 0.988 | 0.655 | 1.684 | 0.571 | 1.029 | 0.781 | 1.465 | |

| > 10 | 0.923 | 0.816 | 1.098 | 0.133 | 0.921 | 0.780 | 1.461 | 0.511 | 1.020 | 0.701 | 2.795 | 0.498 | 1.089 | 0.910 | 1.742 | |

| Memantine | Total | 0.810 | 0.720 | 0.918 | 0.001 | 0.898 | 0.650 | 1.177 | 0.696 | 0.900 | 0.576 | 1.845 | 0.269 | 1.014 | 0.727 | 1.339 |

| = 1 | 0.795 | 0.696 | 0.911 | 0.003 | 0.828 | 0.632 | 1.038 | 0.097 | 0.874 | 0.563 | 1.049 | 0.165 | 0.948 | 0.732 | 1.198 | |

| > 1, = 3 | 0.822 | 0.730 | 0.939 | 0.017 | 0.897 | 0.645 | 1.077 | 0.168 | 0.905 | 0.571 | 1.148 | 0.284 | 1.108 | 0.759 | 1.268 | |

| > 3, = 5 | 0.878 | 0.775 | 1.011 | 0.184 | 0.914 | 0.718 | 1.090 | 0.285 | 1.006 | 0.692 | 1.297 | 0.341 | 1.097 | 0.836 | 1.315 | |

| > 5, = 10 | 0.946 | 0.805 | 1.109 | 0.288 | 0.965 | 0.733 | 1.342 | 0.345 | 1.048 | 0.744 | 1.782 | 0.187 | 1.145 | 0.884 | 1.635 | |

| >10 | 1.016 | 0.900 | 1.219 | 0.425 | 1.003 | 0.820 | 1.616 | 0.619 | 1.086 | 0.779 | 2.366 | 0.298 | 1.215 | 0.998 | 2.027 | |

Table 2: Factors of events among different drugs and tracking interval by using Cox regression and Fine & Gray’s competing risk model.

▪ Usage of ADD and the risk of angina pectoris

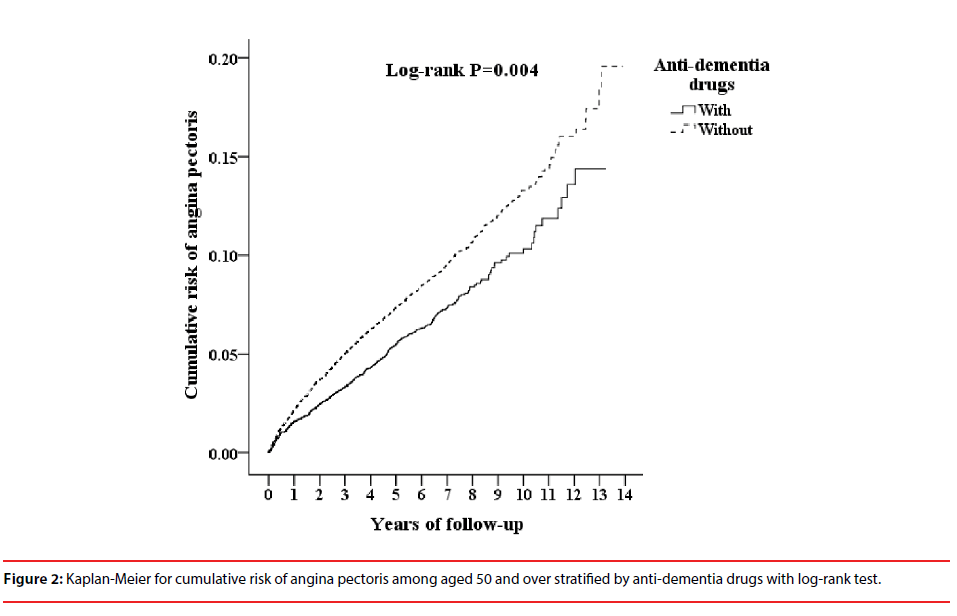

Table 3 shows that ADD usage was associated with a decreased risk of angina pectoris with the follow up period. The cumulative incidence of angina pectoris in the ADD usage cohort and the non-ADD usage cohort, and the differences between the two groups were significant (logrank test=0.004, Figure 2).

| Model | Competing risk in the model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Crude HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | P |

| Anti-dementia drugs | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 0.705 | 0.631 | 0.788 | < 0.001 | 0.761 | 0.679 | 0.853 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 0.988 | 0.885 | 1.103 | 0.829 | 0.967 | 0.865 | 1.081 | 0.557 |

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 50-64 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| = 65 | 1.231 | 0.911 | 1.662 | 0.176 | 1.295 | 0.958 | 1.751 | 0.093 |

| Insured premium (NT$) | ||||||||

| <18,000 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 18,000-34,999 | 1.116 | 0.616 | 2.020 | 0.717 | 1.056 | 0.583 | 1.914 | 0.856 |

| = 35,000 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.977 | 0.000 | - | - | 0.935 |

| CCI_R | 1.401 | 1.072 | 1.852 | < 0.001 | 1.404 | 1.065 | 1.846 | < 0.001 |

| Antidiabetic drugs | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 1.008 | 0.711 | 1.806 | 0.617 | 0.835 | 0.221 | 1.349 | 0.275 |

| Antidepressants | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 0.971 | 0.452 | 1.298 | 0.538 | 0.897 | 0.297 | 1.612 | 0.546 |

| Antipsychotics | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 0.986 | 0.311 | 1.420 | 0.622 | 0.911 | 0.534 | 1.601 | 0.495 |

| Antihypertensive drugs | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 1.213 | 0.454 | 1.975 | 0.497 | 0.875 | 0.654 | 1.457 | 0.775 |

| Benzodiazepines | ||||||||

| Without | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| With | 0.995 | 0.531 | 1.598 | 0.339 | 0.898 | 0.501 | 1.882 | 0.299 |

| Season | ||||||||

| Spring | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Summer | 0.527 | 0.450 | 0.617 | < 0.001 | 0.520 | 0.444 | 0.608 | <0.001 |

| Autumn | 0.695 | 0.593 | 0.814 | < 0.001 | 0.683 | 0.583 | 0.801 | <0.001 |

| Winter | 0.850 | 0.733 | 0.985 | 0.031 | 0.844 | 0.728 | 0.979 | 0.025 |

| Location | ||||||||

| Northern Taiwan | Reference | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | ||||||

| Middle Taiwan | 1.313 | 1.142 | 1.509 | < 0.001 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Southern Taiwan | 1.335 | 1.153 | 1.546 | < 0.001 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Eastern Taiwan | 1.887 | 0.959 | 1.469 | 0.116 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Outlets islands | 0.480 | 0.120 | 1.926 | 0.300 | Multicollinearity with urbanization level | |||

| Urbanization level | ||||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 0.530 | 0.451 | 0.623 | < 0.001 | 0.661 | 0.555 | 0.788 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 0.725 | 0.566 | 0.928 | 0.011 | 0.752 | 0.587 | 0.963 | 0.024 |

| 3 | 0.763 | 0.669 | 0.870 | < 0.001 | 0.929 | 0.807 | 1.070 | 0.308 |

| 4 (The lowest) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Level of care | ||||||||

| Medical center | 0.538 | 0.463 | 0.625 | < 0.001 | 0.637 | 0.538 | 0.754 | <0.001 |

| Regional hospital | 0.643 | 0.568 | 0.727 | < 0.001 | 0.668 | 0.588 | 0.760 | <0.001 |

| Local hospital | Reference | Reference | ||||||

Table 3: Factors of angina pectoris by using Cox regression and Fine & Gray’s competing risk model.

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier for cumulative risk of angina pectoris among aged 50 and over stratified by anti-dementia drugs with log-rank test.

Discussion

In this study, we found that ADD usage was associated with short durations, less than one or two years of a decreased risk of CVE’s, even though the mean interval of usage of the AChEI or memantine was similar to, or slightly shorter, than other studies [14,15,25]. Usage of ADD was associated with a decreased risk of angina pectoris in the follow up period. This is the longest study, 13 years, for the topic on the association between ADD usage and CVE’s risk. Many more modest results have been found in comparison to the previous studies [14,15].

Few previous studies have reported on the impacts on the CVE’s after the discontinuation of ADD usage. In our study, the mean duration of ADD usage was 392.37 (SD=471.24) days, in which the AChEI mean interval was 403.56 (SD=484.77) days, and the memantine was 366.45 (SD=437.26) days. The duration of usage of the AChEI was close to the finding in one previous study in Taiwan, with a mean of 432 days of AChEi usage [25]. Therefore, most of the ADD usage spanned within two years. In addition, our study also showed that the AChEI usage was associated with maxima two years of a lower risk of MI or Ischemic stroke. This finding supports that the AChEI usage was associated with a lower risk of some CVE’s during the treatment time, in a cohort study. However, when the ADD treatment stopped, the benefits gradually vanished, therefore a new study might well be needed to evaluate as to whether the long-term ADD treatment, for example, more than 10 years, is in association with the decreased risk of the CVE’s.

In our study, we examined the lower risk for a specific period of ADD usage, for the CVE’s in MI, ischemic stroke, and angina pectoris in a long-term cohort study. However, several studies have reported the increased risk of syncope, atrioventricular block, and bradycardia, in association with the AChEI’s usage [40,41]. In a comparison study using datasets in the United States Medicare and the Danish healthcare system, memantine was found to be associated with the increased risk of hospitalizations for myocardial infarctions, cardia mortality, and all-cause mortality, especially in the more ailing population [17]. A further study might well be needed to investigate the risk and benefit of ADD usage.

The vagotonic of the AChEI [42,43], and the anti-inflammatory effects of the AChEI and memantine [44-47], which might ameliorate atherosclerosis, could be associated with the effects of the cardiovascular events (CVE’s), including myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke. However, the underlying mechanisms are not clear for ADD usage in either the short-term or longer associations with the decreased risk of CVE’s. We speculate that the vagotonic action dilated cardiac microcirculatory vessels might be associated with the decreased risk of angina pectoris [48]. The reason why only angina pectoris seemed to benefit from the usage of ADD, even long after the mean duration of usage, as aforementioned, remains unclear.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, patients with AD could be identified from using their insurance claims data. However, data on the severity, stage, or impact on their caregivers were not available, and in such a study based on a claims dataset. We could only estimate the treatment durations of each anti-dementia, anti-diabetic, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihypertensive drugs, and benzodiazepines medications by dividing the cumulative doses of the individual medications by DDD. The NHIRD does not contain the image of the coronary angiography or other image findings for myocardial infraction, angina pectoris, CAD and ischemic stroke, either. These CVE’s were defined by the criteria as at least three outpatient visits within the 1-year study period according to these ICD-9-CM codes as aforementioned. Second, other residual confounding factors, such as education, genetics, or dietary factors, are also not included in the NHIRD. Since there is no imaging findings or other laboratory data included in the NHIRD, we could only rely on the professional diagnosis of dementia by the aforementioned board-certified psychiatrists or neurologists. However, since the usage of the ADD must be reviewed by the external reviewers with an expertise in neurology or psychiatry, and with a confirmed diagnosis of AD made after the complete case studies of clinical symptoms and signs, blood tests, cognitive tests and neuro-image work-ups. Third, we could only include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia in the analysis due to the lack of data such as lifestyle, body mass index, or smoking in the NHIRD, a claims database.

Conclusion

The ADD usage was associated with a decreased risk of angina pectoris, but not other CVE’s such as myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, or death, in such a long-term follow up study.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Tri-Service Hospital Research Foundation (TSGH-C105-130, TSGH-C106-002, and TSGH-C107-004), and the sponsor has no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Cummings JL, Cole G. Alzheimer Disease. JAMA 287(18), 2335-2338 (2002).

- Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, et al. Alzheimer's Disease. Lancet 388(10043), 505-517 (2016).

- Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, et al. How Common Are the "Common" Neurologic Disorders? Neurology 685(5), 326-337 (2007).

- Katz MJ, Lipton RB, Hall CB, et al. Age-Specific and Sex-Specific Prevalence and Incidence of Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia, and Alzheimer Dementia in Blacks and Whites: A Report from the Einstein Aging Study. Alzheimer. Dis. Assoc. Disord 26(4), 335-343 (2012).

- Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Forms of Dementia in China, 1990-2010: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Lancet 381(9882), 2016-2023 (2013).

- Kim YJ, Han JW, So YS, et al. Prevalence and Trends of Dementia in Korea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Korean. Med. Sci 29(7), 903-912 (2014).

- Tzeng NS, Chang CW, Hsu JY, et al. Caregiver Burden for Patients with Dementia with or without Hiring Foreign Health Aides: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Northern Taiwan Memory Clinic. J. Med. Sci 35(6), 239-24 (2015).

- Fuh JL, Wang SJ. Dementia in Taiwan: Past, Present, and Future. Acta. Neurol. Taiwan 17(3), 153-161 (2008).

- Tzeng NS, Chiang WS, Chen SY, et al. The Impact of Pharmacological Treatments on Cognitive Function and Severity of Behavioral Symptoms in Geriatric Elder Patients with Dementia. Taiwanese. J. Psychiatry 31(1), 69-79 (2017).

- Chao PC, Chien WC, Chung CH, et al. Cognitive Enhancers Associated with Decreased Risk of Injury in Patients with Dementia: A Nationwide Cohort Study in Taiwan. J. Investig. Med 66(3), 684-692 (2017) .

- Birks J. Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer's Disease. Cochrane. Database. Syst. Rev CD005593(1), 1-107 (2006).

- Mohammad D, Chan P, Bradley J, et al. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for Treating Dementia Symptoms - a Safety Evaluation. Expert. Opin. Drug. Saf 16(9), 1009-1019 (2017).

- Molino I, Colucci L, Fasanaro AM, et al. Efficacy of Memantine, Donepezil, or Their Association in Moderate-Severe Alzheimer's Disease: A Review of Clinical Trials. Scientific. World. J 925702(1), 1-8 (2013).

- Nordstrom P, Religa D, Wimo A, et al. The Use of Cholinesterase Inhibitors and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Death: A Nationwide Cohort Study in Subjects with Alzheimer's Disease. Eur. Heart. J 34(33), 2585-2591 (2013).

- Ku LE, Li CY, Sun Y. Can Persistence with Cholinesterase Inhibitor Treatment Lower Mortality and Health-Care Costs among Patients with Alzheimer's Disease? A Population-Based Study in Taiwan. Am. J. Alzheimers. Dis. Other. Demen 33(2), 86-92 (2018).

- Lin YT, Wu PH, Chen CS, et al. Association between Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Risk of Stroke in Patients with Dementia. Sci. Rep 29266(6), 1 (2016).

- Fosbol EL, Peterson ED, Holm E, et al. Comparative Cardiovascular Safety of Dementia Medications: A Cross-National Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 60(12), 2283-2289 (2012).

- Ho Chan WS. Taiwan's Healthcare Report 2010. EPMA. J 1(4), 563-585 (2010).

- Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Yeh CB, et al. Are Chronic Periodontitis and Gingivitis Associated with Dementia? A Nationwide, Retrospective, Matched-Cohort Study in Taiwan. Neuroepidemiology 47(2), 82-93 (2016).

- Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Lin FH, et al. Headaches and Risk of Dementia. Am. J. Med. Sci 353(3), 197-206 (2017).

- Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Lin FH, et al. Risk of Dementia in Adults with Adhd: A Nationwide, Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan. J. Atten. Disord (2017).

- Chien WC, Chung CH, Lin FH, et al. Is Weight Control Surgery Associated with Increased Risk of Newly Onset Psychiatric Disorders? A Population-Based, Matched Cohort Study in Taiwan. J. Med. Sci 37(4), 137-149 (2017).

- Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Lin FH, et al. Magnesium Oxide Use and Reduced Risk of Dementia: A Retrospective, Nationwide Cohort Study in Taiwan. Curr. Med. Res. Opin 34(1), 163-169 (2018).

- Chinese Hospital Association. Icd-9-Cm English-Chinese Dictionary. Taipei, Taiwan: Chinese Hospital Association Press (2000).

- Sun Y, Lai MS, Lu CJ, et al. How Long Can Patients with Mild or Moderate Alzheimer's Dementia Maintain Both the Cognition and the Therapy of Cholinesterase Inhibitors: A National Population-Based Study. Eur. J. Neurol 15(3), 278-283 (2008).

- Dominguez E, Chin TY, Chen CP, et al. Management of Moderate to Severe Alzheimer's Disease: Focus on Memantine. Taiwan. J Obstet. Gynecol 50(4), 415-423 (2011).

- National Health Insurance Administration. National Health Insurance Reimbursement Audit Guidelines and Notes, for Medications in Neurological Diseases (2015).

- Ministry of Justice. National Health Insurance Reimbursement Regulations (2014)

- Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, et al. Validation of the National Health Insurance Research Database with Ischemic Stroke Cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug. Saf 20(3), 236-242 (2011).

- Chou IC, Lin HC, Lin CC, et al. Tourette Syndrome and Risk of Depression: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr 34(3), 181-185 (2013).

- Liang JA, Sun LM, Muo CH, et al. The Analysis of Depression and Subsequent Cancer Risk in Taiwan. Cancer. Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev 20(3), 473-475 (2011).

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. J. Chronic. Dis 40(5), 373-383 (1987).

- de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, et al. How to Measure Comorbidity. A Critical Review of Available Methods. J. Clin. Epidemiol 56(3), 221-229 (2003).

- Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a Combined Comorbidity Index. J. Clin. Epidemiol 47(11), 1245-1251 (1994).

- Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer Disease. Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Med 2(8), a006239 (2012).

- Needham DM, Scales DC, Laupacis A, et al. A Systematic Review of the Charlson Comorbidity Index Using Canadian Administrative Databases: A Perspective on Risk Adjustment in Critical Care Research. J. Crit. Care 20(1), 12-19 (2005).

- World Health Organization. Who Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology.

- Medalie JH, Goldbourt U. Angina Pectoris among 10,000 Men Ii Psychosocial and Other Risk Factors as Evidenced by a Multivariate Analysis of a Five Year Incidence Study. Am. J. Med 60(6), 910-921 (1976).

- Mack M, Gopal A. Epidemiology, Traditional and Novel Risk Factors in Coronary Artery Disease. Heart. Fail. Clin 12(1), 1-10 (2016).

- Babai S, Auriche P, Le-Louet H. Comparison of Adverse Drug Reactions with Donepezil Versus Memantine: Analysis of the French Pharmacovigilance Database. Therapie 65(3), 255-259 (2010).

- Kroger E, Berkers M, Carmichael PH, et al. Use of Rivastigmine or Galantamine and Risk of Adverse Cardiac Events: A Database Study from the Netherlands. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother 10(6), 373-380 (2012).

- Handa T, Katare RG, Kakinuma Y, et al. Anti-Alzheimer's Drug, Donepezil, Markedly Improves Long-Term Survival after Chronic Heart Failure in Mice. J. Card. Fail 15(9), 805-811 (2009).

- Li M, Zheng C, Sato T, et al. Vagal Nerve Stimulation Markedly Improves Long-Term Survival after Chronic Heart Failure in Rats. Circulation 109(1), 120-124 (2004).

- Jiang Y, Zou Y, Chen S, et al. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Donepezil on Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in C57 Bl/6 Mice. Neuropharmacology 73(1), 415-424 (2013).

- Parmar HS, Assaiya A, Agrawal R, et al. Inhibition of aβ(1-42)Oligomerization, Fibrillization and Acetylcholinesterase Activity by Some Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: An in Vitro Study. Antiinflamm. Antiallergy. Agents. Med. Chem 15(3), 191-203 (2017).

- Pavlov VA, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, et al. Brain Acetylcholinesterase Activity Controls Systemic Cytokine Levels through the Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. Brain. Behav. Immun 23(1), 41-45 (2009).

- Wu HM, Tzeng NS, Qian L, et al. Novel Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Memantine: Increase in Neurotrophic Factor Release from Astroglia and Anti-Inflammation by Preventing Microglial Activation. Neuropsychopharmacology 34(10), 2344-2357 (2009).

- Zamotrinsky AV, Kondratiev B, de Jong JW. Vagal Neurostimulation in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Auton. Neurosci 88(1-2), 109-116 (2001).