Review Article - Interventional Cardiology (2014) Volume 6, Issue 3

Cardiac MRI catheterization: a 10-year single institution experience and review

- Corresponding Author:

- Reza

Razavi

King’s College London BHF Centre, Division of Imaging Sciences

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Tel: +44 207 188 5440

Fax: +44 207 188 5442

E-mail: reza.razavi@kcl.ac.uk

Abstract

Improved surgical and interventional techniques have improved outcomes for congenital heart disease, adding to the number and complexity of lesions needing serial monitoring or treatment. The role of MRI in the assessment of cardiac anatomy and function in congenital heart disease is well established and has the potential to replace diagnostic cardiac catheterization in selected cases. However, x-ray-guided cardiac catheterization is still necessary for invasive hemodynamic data and cardiac interventions.Keywords

cardiac catheterization, catheter interventions, congenital heart disease, dobutamine stress, MRI, pulmonary vascular resistance

Improved surgical and interventional techniques have improved outcomes for congenital heart disease [1], adding to the number and complexity of lesions needing serial monitoring or treatment. The role of MRI in the assessment of cardiac anatomy and function in congenital heart disease is well established and has the potential to replace diagnostic cardiac catheterization in selected cases [2–7]. However, x-ray-guided cardiac catheterization is still necessary for invasive hemodynamic data and cardiac interventions.

Role of MRI- & combined x-ray & MRI-guided catheterization

There has been interest in developing MRI as an alternative to x-ray for guiding cardiac catheterization because of three key drawbacks of x-rays. The risk of tumor formation from repeated x-ray catheterization is well established [8–12]. The difficulty of visualizing the key cardiovascular structures during the manipulation of catheters and devices without multiple injections of iodine x-ray contrast agents is also particularly an issue in patients with congenital/structural abnormalities. Finally, being able to measure key physiological parameters such as pulmonary blood flow and ventricular volumes during cardiac catheterization is often important, but difficult under x-ray guidance.

MRI-guided and combined x-ray and MRI (XMR) catheterizations were first introduced into the clinical forum a decade ago [6] out of the need to address these drawbacks. MRI can be considered as an adjunct or an alternative to x-ray during catheterization procedures. Where invasive pressure measurements are required, MRI-guided and XMR cardiac catheterization has been proven to reduce the screening time and radiation dose [6,13]. Fluoroscopic screening is limited to guiding catheter positioning with the use of guide wires that are not MRI safe due to concerns around heating. Catheter manipulation under MRI has the advantage of soft tissue visualization not seen on conventional x-ray-guided catheterization. Additionally, MRI allows for easy manipulation of imaging planes, thus reducing the need for multiple fluoroscopic projections to identify the area of interest. MRI also allows accurate quantification of ventricular volumes, cardiac output and flow within vessels, such as accurate quantification of pulmonary blood flow. This can be used in combination with an invasive catheter transpulmonary pressure gradient to measure pulmonary vascular resistance accurately.

MRI catheterization in clinical practice

We reported the first clinical experience of MRI- and XMR-guided cardiac catheterizations at our institution [6,14]. MRI-guided and XMR catheterizations were subsequently validated against standard cardiac catheterization for the clinical assessment of pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) [6,13,15]. In the past few years, the indications have widened to include assessment of anatomy and function, cardiac output and hemodynamic measurements during pharmacological stress [2,7,16]. This has included successful MRI-guided catheterization without the need for x-ray [6,13–15,17]. We have also described an initial clinical experience of MRI-guided structural cardiac interventions using an MRI-compatible guide wire [18]. MRI catheterization has been described in the clinical setting, but this continues to be in a limited number of centers and in small numbers [2,6,13–15,17–23]. In fact, the total number of patients described in the literature combining all of these clinical studies and reports to date only equates to 142.

Single institution experience of clinical MRI-guided & XMR catheterization

We report a large 10-year experience of clinical MRIguided and XMR catheterization in patients at our institution, review the developments in clinical MRIguided and XMR catheterization and discuss future perspectives. This includes further results from our clinical trial on MRI-guided cardiac interventions.

MRI techniques

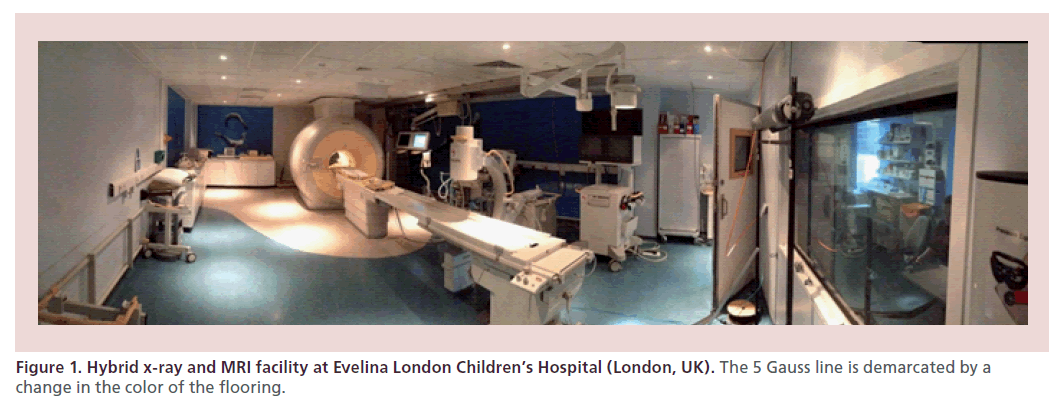

The techniques of MRI-guided and XMR catheterization have been previously described [6,13,17,18,24,25]. The imaging requirements from MRI for the purpose of catheterization have also been extensively described [6,24,25]. MRI-guided and XMR catheterizations take place in a specifically designed catheterization laboratory with combined x-ray and MRI facilities (Figure 1). In our laboratory, we use a 1.5 T magnetic resonance (MR) scanner (Achieva, Philips, Best, The Netherlands) and a Philips BV Pulsera cardiac x-ray unit. In-room monitor and controls display MRI images and hemodynamic pressure traces. The table-top design allows patients to be moved from one modality to the other in a very short time. MRI-compatible patient monitoring and anesthetic equipment is used. A comprehensive standard operating procedure is in place, which has been extensive described by Tzifa et al. [24], with a particular focus on safety within the MRI environment. All procedures are performed under general anesthesia. A heparin bolus of 50 IU/kg is given with activated clotting time monitoring once vascular access is obtained.

The ECG system employed during cardiac catheterization is a commercial hemodynamic tracer system EP Tracer 102 (CardioTek BV, Maastricht, The Netherlands). The invasive pressure component of the system is used throughout the procedure. However, the ECG component is not MRI compatible and removed prior to transfer into the MRI bore. While in the MRI bore, the patient monitoring system used by the anesthetic team (Datex Ohmeda, GE, CT, USA), which is MRI compatible, is used for monitoring.

MRI protocols

In all patients, a similar MRI protocol is followed as described below to assess anatomy, ventricular function and vascular flow. A free-breathing, dual-phase respiratory-gated and ECG-triggered 3D steady-state free precision (SSFP) scan of the heart and great vessels and 3D contrast-enhanced MR angiography is performed to elucidate intracardiac and vascular anatomy. The 3D SSFP image is acquired in a sagittal orientation (repetition time (TR): 3.4 ms; echo time (TE): 1.7 ms; flip angle: 90°; isotropic resolution: 1–1.5 mm3;acquisition window: 60–75 ms; respiratory gating window: 3–5 mm). Contrast-enhanced MRI angiography was acquired with first-pass 3D angiography using 0.2 ml/kg bodyweight gadoterate meglumine (Dotarem, Guerbet, Villepinte, France).

To calculate ventricular volumes and function, short axis cuts of the ventricle(s) are obtained using retrospective ECG-gated SSFP 2D cine sequences (TR: 3.1–3.6 ms; TE: 1.6–1.8 ms; acceleration factor [SENSE acquisition]: 2; flip angle: 60°; field of view: 200–320 mm; slice thickness: 4–8 mm; in plane resolution: 1.3–2.0 mm; acquired temporal resolution: 30–40 phases; phase percentage: 80–100; breath-hold duration: 11–15 s; 10–14 slices).

To obtain blood flow measurements in major vessels, through plane velocities are measured by means of through plane phase-contrast gradient-echo sequences perpendicular to the long axis planes of the vessel with either breath-hold or free-breathing flow-sensitive segmented k-space fast-field echo sequence (approximate echo time: 3 ms; approximate repetition time: 5 ms; matrix: 128 × 256; field of view: 250–350 mm; flip angle: 15°; three signal averages for free-breathing sequences; retrospective gating; 40 acquired phases).

XMR-guided catheterization

For XMR catheterization procedures, catheters are positioned in the appropriate vessels and chambers using guide wires where necessary under x-ray guidance. Once right and/or left heart catheterization is complete, MRI-compatible catheters (Wedge catheter, Arrow, PA, USA) are left in place for continuous hemodynamic pressure monitoring and the patient is transferred to the MRI scanner on the sliding table. Cardiac MRI is performed to measure ventricular volumes, function and phase-contrast flows, as above, with simultaneous pressure measurements.

MRI-guided catheterization

Following an initial reference scan, an interactive sequence is used for determining and saving reference planes for catheter guidance. For example, for right heart catheterization, the following views are stored: sagittal and coronal views of the superior vena cava/inferior vena cava, four-chamber, right ventricular outflow tract, right heart two-chamber view, pulmonary artery (PA) bifurcation, left PA sagittal and right PA coronal views.

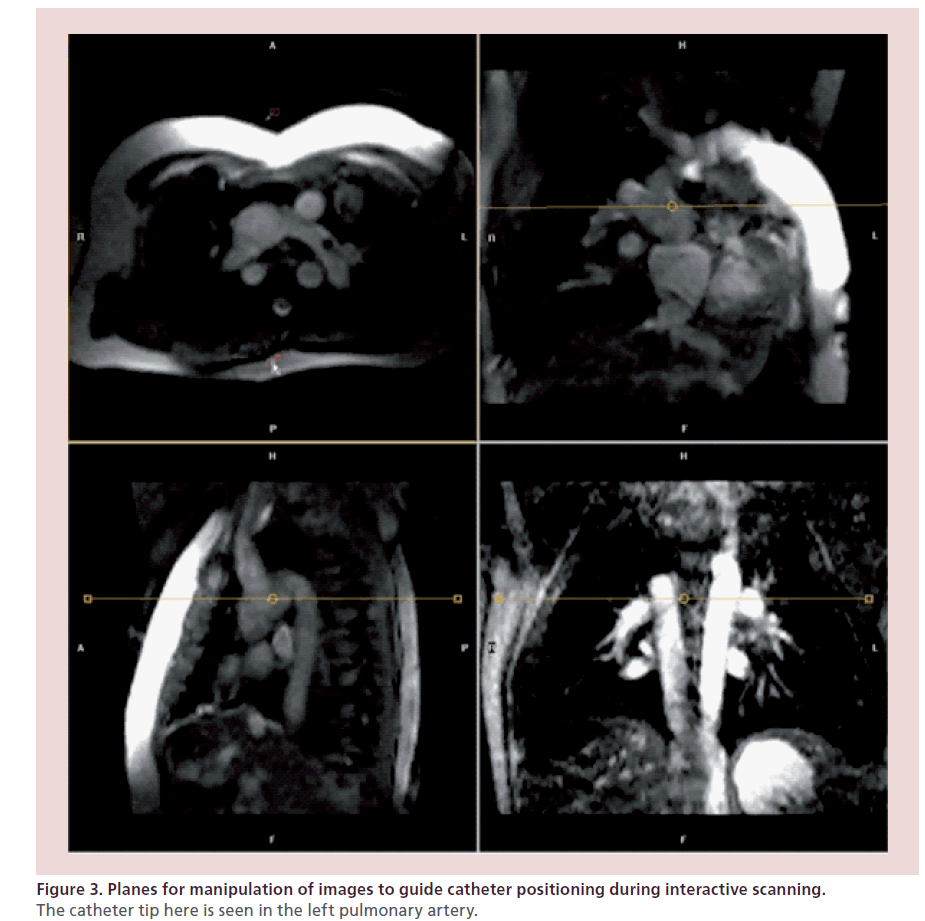

During passive catheter tracking, a 2D SSFP sequence; balanced fast field echo; TE: 1.45 ms; TR: 2.9 ms; matrix: 128 × 128), with a temporal resolution of 10–14 frames per second is used, in which the catheter tip is seen filling the angiographic balloon with 1 ml of carbon dioxide (Figure 2) [6,14]. The interactive mode also allows manipulation of the slice plane and other variables during scanning to follow the catheter manipulation (Figure 3). The operators can start and stop the MRI scan independently, switch between the four imaging planes displayed on an in-room console and move the imaging plane in either through plane direction using foot pedals that control the scanner console. Once catheters are in place, MRI imaging is performed to measure ventricular volumes, function and phase-contrast flows as above with simultaneous pressure measurements.

Physiological measurements

The following physiological measurements with values indexed to body surface area are calculated during the MRI-guided and XMR catheterization:

• The quantity and ratio of pulmonary and systemic blood flow is measured by phase contrast through plane imaging of the major vessels supplying the systemic and pulmonary circulation. In patients with multiple sources of pulmonary blood flow, each source is calculated separately. Where it was not possible to measure the blood flow from a particular source (e.g., Blalock–Taussig shunt), this is inferred by measuring flow in the branch pulmonary arteries, or by measuring flow in major vessels on either side of the source or by measuring the difference between the superior vena cava and descending aortic flow.

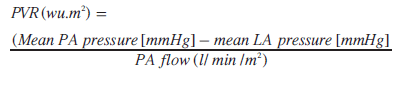

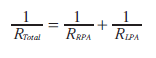

• PVR:

Left atrial pressure is either measured directly or obtained from a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure accepting that pulmonary capillary wedge pressure only remains a reliable measure of left atrial pressure at values <15 mmHg. Units are expressed as woods units (wu) indexed to body surface area (wu.m2). Mean PA pressure is either measured in the main PA or branch PAs. Where branch PA flows and pressures are used, we measured individual lung PVR and calculated a total PVR.

Clinical protocols

Invasive pressure and phase-contrast flow are measured simultaneously and repeated under different physiological conditions. Throughout, we aimed for hemodynamic stability in the patient and normocarbia (PaCO2:4–5 kPa). Structured protocols used are described below and employed for both MRI-guided and XMR catheterization:

• PVR studies: baseline measurements are made in 30% inspired oxygen. Patients undergoing reversibility studies have repeat measurements 20 min after administration of inhaled nitric oxide at 20 ppm and 100% inspired oxygen;

• Dobutamine stress studies: these studies involved measurements of cardiac output and invasive pressures at baseline and repeated with dobutamine infused at a rate of 10 μg/kg/min for 10 min or once a stable heart rate or blood pressure rise had been observed and repeated at 20 μg/kg/min;

• Isoprenaline stress studies involved measurement of aortic blood flow and pressure gradients across the site of aortic coarctation at baseline and with isoprenaline (isoprenaline sulfate) at a dose of 0.02 μg/kg/min increasing to a maximum of 0.7 μg/kg/min. The dose is titrated upwards until the heart rate increased by ≥50% from baseline and maintained once a stress steady state was achieved.

Single institution results

A total of 214 studies were performed in 187 patients from a retrospective analysis of pediatric and adult patients who underwent MRI-guided and XMR cardiac catheterizations in our institution between February 2002 and February 2012. In total, 134 of the 187 patients had previous surgical or catheter interventions; 21 patients had a single repeat MRI-guided and XMR study and three patients had two repeat MRIguided and XMR studies. Median age and weight was 4.5 years (4 days–64.7 years) and 15.4 kg (2.3–106 kg), respectively. Furthermore, 189 were XMR catheterizations; 25 were solely MRI-guided cardiac catheterizations, of which seven were part of the first-in-man clinical trial on MRI-guided cardiac interventions. A total of 110 studies led to a cardiac intervention and ten liver transplants at a median interval of 47 days (0–763 days) based wholly or in part on the XMR data. Median radiation dose for MRI-guided and XMR was 3.78 Gy cm2 (0.75 mSv; range: 0–57.5 Gy cm2), with a median screening time of 11.0 min (range: 0–66.5 min). Details of the procedures are listed in order of: PVR; pharmacological stress studies; hybrid x-ray and MRI-guided interventions; and solely MRI-guided interventions.

PVR

PVR was assessed in 175 of 214 studies where there was a suspicion of raised PA pressures based on echocardiographic or clinical findings. Median age was 3.6 years (6 days–67 years) and weight 13.8 kg (2.3–122 kg). We and others [6,13,15] have previously shown that PVR calculated during MRI-guided and XMR catheterization is more accurate than the standard Fick technique, particularly following pulmonary vasodilation. It is institutional practice to base surgical decision-making for these patients on clinical findings, echocardiography and MRI data without routine diagnostic catheterization [7]. Patients progressing along the path of surgical single ventricle palliation undergo an MRI with simultaneous measurement of central venous pressure. Therefore, patients referred for MRIguided and XMR evaluation were of a cohort with a high suspicion of abnormal anatomy or hemodynamics requiring more thorough evaluation.

Pharmacological stress studies

In total, 46 patients underwent 54 MRI-guided and XMR catheterization studies to assess the hemodynamic response to pharmacological stress. Three categories were defined:

• Preliver transplant assessments in patients with liver disease. Dobutamine stress studies were performed to assess right ventricular pressure and cardiac output response to stress in line with the criteria for assessment previously described [24,26];

• Patients with a functionally univentricular circulation and coexisting resultant morbidity (proteinlosing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, exercise intolerance (New York Heart Association class ≥2), in whom complete hemodynamic assessment combined with cardiac output studies were performed at rest and with dobutamine stress;

• Patients with borderline coarctation of the aorta undergoing pharmacological stress with isoprenaline to assess the need for intervention.

Dobutamine stress studies in children and adults have been utilized safely [26–30]. It is our experience that given the correct monitoring, dobutamine at up to a dose of 20 μg/kg/min can be administered safely in children and adults during MRI-guided and XMR catheterization. Pharmacological stress studies using MRI-guided and XMR catheterization was applied in the assessment of patients with liver disease or functionally univentricular hearts, where accurate assessment of changes in the cardiac output and simultaneous recording of hemodynamic data is very helpful.

It is known that patients with fixed right heart obstruction are unable to raise their cardiac output at stress and this is relevant in the immediate postliver transplantation period where a substantial rise in cardiac output is observed and, if not possible, can lead to poor outcomes [31–34]. It is therefore important to identify the presence and significance of any hemodynamic obstructions in order to deal with them prior to the transplantation [2–5,16,26,35]. MRI-guided and XMR provides both anatomical and hemodynamic information in one sitting, and we were able to identify patients who require interventions to relieve right ventricular outflow tract obstruction and were able to restudy them postintervention to confirm a reduction in right ventricular pressure to values of less than half of systemic systolic pressures and increase in cardiac output of at least 40% with dobutamine stress who can then be put before forward for successful liver transplantation.

Isoprenaline stress studies in aortic coarctation provided an assessment of arch anatomy and invasive gradients in patients deemed to have a borderline substrate for intervention at initial assessment. It unmasks important gradients across the coarctation site not seen under resting conditions, thus providing further diagnostic information to plan management.

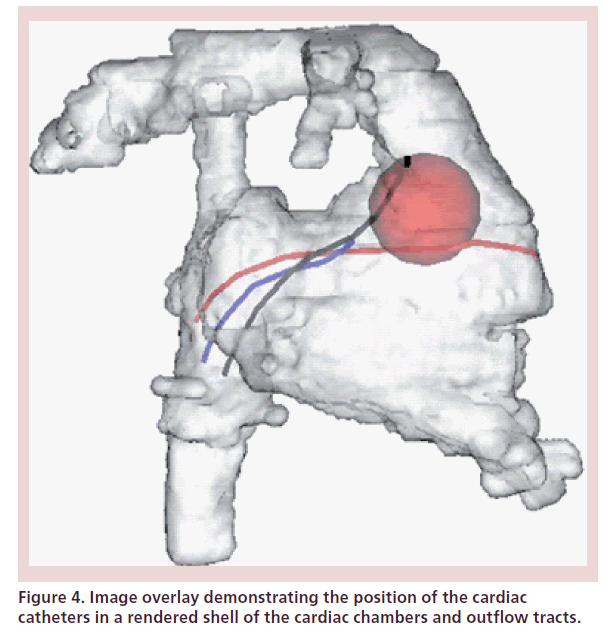

Combined x-ray & MRI-guided interventions

Combined x-ray-guided interventions and MRI imaging were performed in the early series of our clinical experience. This included one atrial septal defect closure, one device occlusion of a hemi-Fontan baffle leak and two coarctation stents. We were able to use the 3D anatomy acquired during the MRI as an anatomical model to guide the x-ray fluoroscopic intervention, which would have not been possible under MRI guidance alone because of the risk of heating of the guided wire or delivery devices used. The registration technique between the 3D MRI anatomy and real-time fluoroscopy images has been previously described by our group [36,37] and that of Lederman et al. [38,39]. All of these interventions were performed under complete fluoroscopic guidance in the XMR suite and the patients were then transferred immediately back to the MRI to assess the results of the intervention. This type of technology [36], where preacquired 3D anatomy from MRI or computed tomography (CT) is used to guide fluoroscopic interventions is now more widely available as a product from the imaging vendors in the standard x-ray fluoroscopic catheter laboratory setting (Figure 4).

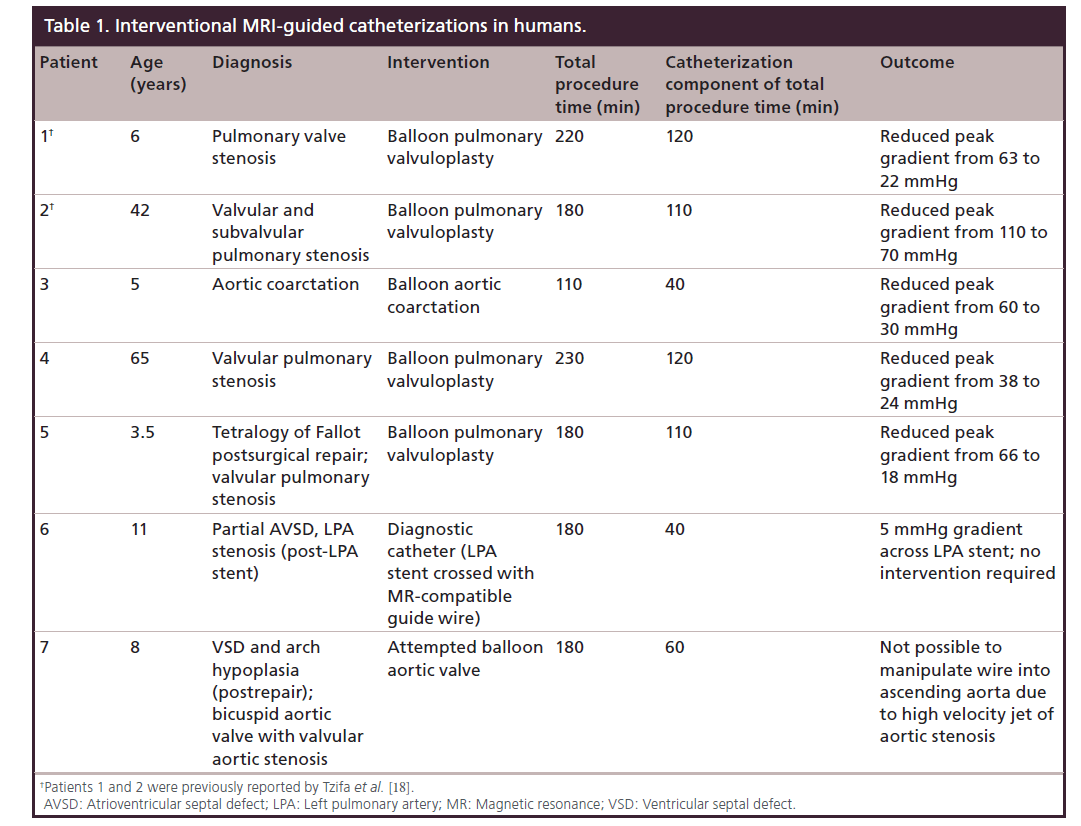

Solely MRI-guided interventions

Seven patients aged 3–64 years were recruited in the clinical trial of MRI-guided interventions using a novel MR-compatible fiberglass guide wire [18]. Details of the first two patients in this group have been previously published [18]. Details of the patients and procedures are listed in Table 1. Median procedure and catheterization times were 180 and 110 min, respectively. Five patients underwent successful interventions for pulmonary valve stenosis (n = 4) and native aortic coarctation (n = 1). One patient with a left PA stent underwent right heart catheterization using the MRI-compatible wire, but the gradient across the stent was only 5 mmHg, hence no intervention was required. The last patient with severe aortic stenosis had an unsuccessful attempt at ballooning the aortic valve. This was due to the inability to direct the guide wire or catheter into the ascending aorta against the high velocity jet of aortic stenosis.

All but the last patient were discharged home the day after the procedure with >50% reduction of the stenosis gradient in all five patients who had an intervention with no procedural complications. The last patient with an unsuccessful attempt at crossing the aortic valve returned to the catheterization laboratory for fluoroscopic-guided valvuloplasty a few weeks later. During initial screening, it became clear that a segment of the MRI-compatible guide wire had fractured during the MRI-guided procedure and was now left in the body, but could not be retrieved by snaring and a conservative approach was taken as it appeared well embedded in the vascular wall. The patient had a successful fluoroscopy-guided aortic valve balloon valvuloplasty. The patient subsequently had the wire surgically removed uneventfully with no further incidents. The clinical trial was discontinued at that point and the adverse event was reported to the Regulatory Authority.

Complications

There are no reported complications related to MRIguided and XMR catheterizations, which may in part be due to the nature of the few small series published to date. However, we know from larger series of combined conventional diagnostic and interventional pediatric cardiac catheterizations, the actual total complication rate is approximately 8.8%, with the majority of these being minor complications [40,41]. Mortality remains low at 0.14 [40] to 0.28% [42]. In our large cohort, there were three immediate complications, one late complication and no procedural deaths. One patient had a pulmonary hemorrhage during cardiac catheterization requiring an additional day of ventilation on intensive care. The second immediate complication related to the fractured MRI-compatible wire as described above. The third patient had end-stage liver disease and experienced transient ventricular tachycardia without loss of cardiac output during administration of dobutamine at 20 μg/kg/min. This was noted immediately and resolved on discontinuation of the dobutamine infusion with no active intervention required. The late complication was in an adult who was readmitted from the community having suffered from a deep vein thrombosis 4 days after the MRIguided catheterization. A CT angiogram confirmed multiple small pulmonary emboli. The patient was treated with standard anticoagulation therapy and made a full recovery.

Radiation

Despite the need for x-ray fluoroscopy, the radiation doses in MRI-guided and XMR catheterization remain low. The median radiation exposure of 0.75 mSv over 10 years compares favorably against conventional fluoroscopic diagnostic catheterization in contemporary literature of 10.8 mSv [43]. Our findings therefore support the argument that MRI-guided and XMR catheterization reduces radiation exposure for congenital patients as reported previously [6].

Challenges in MRI catheterization

The developments in MRI catheterization have been subject to several reviews [25,27–29,44–47] and editorials [31–34,48], with an enthusiasm for the technique stressing the excellent potential of this technique within routine clinical practice. However, MRI catheterization has been slow to develop over the past decade and its current use remains limited to a few centers.

The challenges to this development have remained fairly similar in that time, with recent advances outlined below. These relate to the MRI environment, scanning capabilities and the availability of MRI-compatible guide wires, catheters and devices.

MRI environment

Most of the centers practicing XMR/MRI catheterization have purpose-built XMR/MRI laboratories, which are expensive and require a skilled multidisciplinary team, which includes clinicians with expertise in MRI and cardiac catheterization supported by MRI physicists and other technical specialists to establish a successful clinical program. Where this is not available, centers can employ a combination of x-ray-guided catheterization in a separate laboratory, with subsequent transfer of the patient to the MRI suite with MRI-compatible catheters in situ for diagnostic studies provided patient safety is not compromised. Access to the patient during catheterization has also been limited by the bore size of the scanner, but this is less of an issue with the newer generation of MRI scanners with a wider bore. Additionally, improved MRI-compatible hardware is being developed for hemodynamic monitoring of patients [49].

Catheter tracking

Visualization of the catheters under MRI guidance has also been challenging. We employed passive catheter tracking in our unit, using the susceptibility artefact and resultant signal void from the carbon dioxide-filled balloon catheter balloon tips to track the catheter tip for manipulation [14]. Other groups have advocated using gadolinium-filled balloon tips in place of carbon dioxide for improved catheter tip visualization and steering [17]. Passive catheter tracking, however, lacks the ability to visualize the entire shaft of the catheter, which makes it susceptible to unrecognized coiling and twisting of the catheter. The alternative is active catheter tracking where the device is electrically connected to the MRI scanner and has a coil or antenna that is able to transmit or transmit and receive. Ratnayaka et al. [25] have summarized the key aspects of comparison between active and passive catheter tracking. Active catheter tracking offers the best prospect for improved dynamic visualization and with new technology, that addresses safety issues, should become much more widely used in the future [17,50,51].

MRI-guided interventions

In the past MR-guided interventions have only been performed in animals due to lack of MR compatible and safe interventional equipment. These have included atrial septal defect device closure [52,53], transeptal puncture [54], stenting of aortic coarctation [55] and percutaneous implantation of aortic valve [56]. However, the lack of appropriate hardware has limited its application in humans where MRI remained an adjunct to x-ray guidance [19]. The availability of a new MR-compatible and safe fiberglass passive guide wire [57] led to a successful preclinical trial of solely MR-guided interventions leading to a first-in-man intervention performed by our group and applied to several other patients as described above [18]. Although we were able to demonstrate the feasibility of performing solely MR-guided diagnostic cardiac catheterizations, the prototype guide wire did not have adequate mechanical properties for safe application despite satisfactory preclinical testing.

Catheter & guidewire development

There needs to be further developments in MRguided catheter steering, which can be achieved either by using guide wires as mentioned previously or catheter development. Recent catheter developments [58] to aid steering and visualization in the MRI environment include catheter tip ferromagnetic beads [59,60], catheter tip microcoils [61] and microfluidic hydraulic catheters. The imaging of the latter is dependent on the nature of the hydraulic fluid. Smart material actuators [62] in catheter development provide better steering without the benefit of improved visualization.

Further developments in this field are ongoing and new devices are being developed with improved mechanical properties. Once these devices have obtained regulatory approval then solely MRIguided cardiac catheterization both for diagnostic and interventional purposes will become much more feasible.

Image registration & overlay

The increasingly complex nature of procedures will ultimately benefit from integrating a wide range of imaging modalities to impart a comprehensive view of the cardiac structures for the interventionists. It is crucial to consistently maintain correct alignment of the images from the different modalities being used. Image registration techniques are constantly improving to allow overlay of echocardiographic, MRI or CT images and fluoroscopy into the same image with improved alignment and minimal motion artefact from respiration [36,63–66].

Other applications

Progress has been made since the first clinical application of MRI electrophysiology [20], with advances in its use limited to animals [67,68]. Newer catheters with full diagnostic electrophysiology functionality with active tracking [51] have been developed. Sommer et al. [23] recently published the first series of patients with realtime MRI-guided placement of multiple catheters with subsequent performance of stimulation maneuvers in five adult patients. These developments are highly relevant to patients with congenital heart following complex surgery where there is a recognized burden of arrhythmia [69]. Additionally, intramyocardial stem cell [70,71] or gene treatments [72] with MRI-guided and XMR catheterization has been shown to be technically possible in previous animal models and offers promising potential for due to the advantages in soft tissue visualization.

Conclusion

MRI-guided and XMR catheterization is a safe and useful clinical tool, but requires specialist hardware and a skilled multidisciplinary team. There are clear developments to be made in the field, which rely heavily on hardware development before we see MRI-guided and XMR catheterization being widely employed in routine clinical practice. Continued developments require the support of industry both for scanner and catheter or device development.

Future perspective

MRI-guided and XMR catheterization has a significant potential for wide clinical application but remains limited by cost, hardware and software development. There is renewed enthusiasm to develop these technologies. It has particular relevance in congenital and structural heart disease where continued developments in surgical and interventional techniques add to the complexity of patients needing assessment and treatment. Our experience as a unit has demonstrated that these techniques, which were initially part of a research program, have now come into routine clinical practice for diagnostic studies.

The potential for MRI-guided cardiac interventions is significant and relevant. The lesions where these techniques were initially applied were for relatively straightforward lesions, such as ballooning of the pulmonary valve, which are not technically complicated using existing x-ray methods. The reduction in radiation dose exposure in these cases is small. The real benefit for MRI-guided interventions in congenital heart disease will be for complex procedures where visualization of important soft tissue structures are required, such as device closure of ventricular septal defects and stenting of aortic coarctation. This will not only allow the operator better periprocedural imaging to guide device or stent positioning, but offer the ability to immediately measure any residual shunts and assess vessel walls for any damage, such as dissection. MRI catheterization also offers exciting potential in electrophysiology, with the ability to directly visualize the ablation substrate in patients with or without congenital heart disease.

The two main obstacles for much wider use of this technology have been MRI-compatible catheters and guide wires and an interventional software platform specifically for MRI cardiac catheterization. In addition, safe active tracking of catheters and guide wires that is displayed within the interventional platform would be the game-changing innovation that would make MRI-guided catheterization a mainstream clinical tool. Over the last 3 years, a number of device companies (including smaller start-ups) and two major MRI vendors have instigated major research and development programs to overcome these obstacles. There are now, for example, CE-marked MRI-compatible guide wires (EPFlex, Dettingen/Erms, Germany developed with Melzer IMSAT, Dundee, UK) with passive markings and prototype interventional software platforms, such as the Philips iSuite, which is about to be used as part of a clinical trial in patients. As these innovations progress into products, then the field will expand and MRI-guided catheterization will become more widely used.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the MRI department at Evelina London Children’s Hospital (London, UK).

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Executive summary

Advantages of MRI catheterization over x-ray-guided catheterization

• Reduced radiation exposure.

• Improved visualization of anatomy and soft tissue structures.

• Provides detailed and accurate assessment of physiological and hemodynamic measurements such a ventricular volumes, flow within vessels and vascular resistance when combined with invasive data.

Current applications of MRI-guided & combined x-ray and MRI catheterization in the literature

• Pulmonary vascular resistance studies.

• Pharmacological stress studies (e.g., dobutamine stress studies) of cardiac reserve.

• MRI-guided interventions in congenital heart disease.

Developments to lead the advancement of the technique

• MRI environment

–– Increasing number of purpose-built combined x-ray and MRI/MRI laboratories to facilitate the technique, but separate laboratories within close proximity could be utilized for diagnostic studies.

–– Improved MRI-compatible hardware and software for patient monitoring and hemodynamic assessment.

–– Larger bore size allowing for better access to the patient.

–– Improved MRI scanning technology for fast scans and improved imaging quality.

• Catheter tracking

–– Ongoing developments of active catheter tracking have distinct advantages over current passive catheter tracking techniques, which will allow for better visualization of the catheter.

Catheter steering

• Guide wire development

–– Advancement of MRI-guided interventions has been limited by the availability of a suitable guidewire.

–– A suitable MRI-compatible guide wire is crucial for the advancement of MRI-guided catheterization, particularly in congenital heart disease were manipulation of needed to negotiate the complex anatomy.

• Catheter development

–– Newer catheter developments with in-built adaptations for visualization and steering mechanisms are being developed.

Future applications

• MRI-guided cardiac interventions. This includes balloon valvuloplasty, device occlusion and stenting procedures.

• Cardiac electrophysiology studies and ablation.

• Delivery of targeted stem cell or gene treatments.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The Division of Imaging Sciences receives support as the Centre of Excellence in Medical Engineering (funded by the Wellcome Trust and EPSRC; grant number WT 088641/Z/09/Z) as well as the BHF Centre of Excellence (British Heart Foundation award RE/08/03). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, Rahme E, Pilote L. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation 115(2), 163–172 (2006).

- Schmitt B, Steendijk P, Ovroutski S et al. Pulmonary vascular resistance, collateral flow, and ventricular function in patients with a Fontan circulation at rest and during dobutamine stress. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 3(5), 623–631 (2010).

- Heathfield E, Hussain T, Qureshi S et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in congenital heart disease as an alternative to diagnostic invasive cardiac catheterization: a single center experience. Congenit. Heart Dis. 8(4), 322–327 (2013).

- Brown DW, Gauvreau K, Powell AJ et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance versus routine cardiac catheterization before bidirectional glenn anastomosis in infants with functional single ventricle: a prospective randomized trial. Circulation 116(23), 2718–2725 (2007).

- Fogel MA, Pawlowski TW, Whitehead KK et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance and the need for routine cardiac catheterization in single ventricle patients prior to Fontan: a comparison of 3 groups: pre-Fontan CMR versus cath evaluation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60(12), 1094–1102 (2012).

- Razavi R, Hill DLG, Keevil SF et al. Cardiac catheterisation guided by MRI in children and adults with congenital heart disease. Lancet 362(9399), 1877–1882 (2003).

- Muthurangu V, Taylor AM, Hegde SR et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging after stage I Norwood operation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Circulation 112(21), 3256–3263 (2005).

- Hall EJ, Brenner DJ. Cancer risks from diagnostic radiology. Br. J. Radiol. 81(965), 362–378 (2008).

- Andreassi MG, Ait-Ali L, Botto N, Manfredi S, Mottola G, Picano E. Cardiac catheterization and long-term chromosomal damage in children with congenital heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 27(22), 2703–2708 (2006).

- Andreassi MG, Cioppa A, Manfredi S, Palmieri C, Botto N, Picano E. Acute chromosomal DNA damage in human lymphocytes after radiation exposure in invasive cardiovascular procedures. Eur. Heart J. 28(18), 2195–2199 (2007).

- Bacher K, Bogaert E, Lapere R, De Wolf D, Thierens H. Patient-specific dose and radiation risk estimation in pediatric cardiac catheterization. Circulation 111(1), 83–89 (2005).

- Modan B, Keinan L, Blumstein T, Sadetzki S. Cancer following cardiac catheterization in childhood. Int. J. Epidemiol. 29(3), 424–428 (2000).

- Muthurangu V, Taylor A, Andriantsimiavona R et al. Novel method of quantifying pulmonary vascular resistance by use of simultaneous invasive pressure monitoring and phase-contrast magnetic resonance flow. Circulation 110(7), 826–834 (2004).

- Miquel ME, Hegde S, Muthurangu V et al. Visualization and tracking of an inflatable balloon catheter using SSFP in a flow phantom and in the heart and great vessels of patients. Magn. Reson. Med. 51(5), 988–995 (2004).

- Kuehne T, Yilmaz S, Schulze-Neick I et al. Magnetic resonance imaging guided catheterisation for assessment of pulmonary vascular resistance: in vivo validation and clinical application in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Heart 91(8), 1064–1069 (2005).

- Bellsham-Revell HR, Tzifa A, Hussain T et al. Dobutamine stress MRI catheterisation in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after Fontan completion: preliminary results. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 13(Suppl. 1), P212 (2011).

- Ratnayaka K, Faranesh AZ, Hansen MS et al. Real-time MRI-guided right heart catheterization in adults using passive catheters. Eur. Heart J. 34(5), 380–389 (2013).

- Tzifa A, Krombach GA, Krämer N et al. Magnetic resonance-guided cardiac interventions using magnetic resonance-compatible devices: a preclinical study and firstin- man congenital interventions. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 3(6), 585–592 (2010).

- Krueger JJ, Ewert P, Yilmaz S et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided balloon angioplasty of coarctation of the aorta: a pilot study. Circulation 113(8), 1093–1100 (2006).

- Nazarian S, Kolandaivelu A, Zviman MM et al. Feasibility of real-time magnetic resonance imaging for catheter guidance in electrophysiology studies. Circulation 118(3), 223–229 (2008).

- Bell A, Beerbaum P, Greil G et al. Noninvasive assessment of pulmonary artery flow and resistance by cardiac magnetic resonance in congenital heart diseases with unrestricted leftto- right shunt. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2(11), 1285–1291 (2009).

- Tzifa A,Razavi R. Test occlusion of Fontan fenestration: unique contribution of interventional MRI. 97(1), 89 (2011).

- Sommer P, Grothoff M, Eitel C et al. Feasibility of real-time magnetic resonance imaging-guided electrophysiology studies in humans. Europace 15(1), 101–108 (2012).

- Tzifa A, Schaeffter T, Razavi R. MR imaging-guided cardiovascular interventions in young children. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 20(1), 117–128 (2012).

- Ratnayaka K, Faranesh AZ, Guttman MA, Kocaturk O, Saikus CE, Lederman RJ. Interventional cardiovascular magnetic resonance: still tantalizing. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 10(1), 62 (2008).

- Razavi RS, Baker A, Qureshi SA et al. Hemodynamic response to continuous infusion of dobutamine in Alagille’s syndrome. Transplantation 72(5), 823 (2001).

- Strigl S, Beroukhim R, Valente AM et al. Feasibility of dobutamine stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in children. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 29(2), 313–319 (2009).

- Robbers-Visser D, Luijnenburg SE, van den Berg J et al. Safety and observer variability of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging combined with low-dose dobutamine stress-testing in patients with complex congenital heart disease. Inter. J. Cardiol. 147(2), 214–218 (2011).

- Robbers-Visser D, Jan Ten Harkel D, Kapusta L et al. Usefulness of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging combined with low-dose dobutamine stress to detect an abnormal ventricular stress response in children and young adults after fontan operation at young age. Am. J. Cardiol. 101(11), 1657–1662 (2008).

- Parish V, Valverde I, Kutty S et al. Dobutamine stress MRI in repaired tetralogy of Fallot with chronic pulmonary regurgitation: a comparison with healthy volunteers. Inter. J. Cardiol. 166(1), 96–105 (2011).

- Geva T. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided catheter interventions in congenital heart disease. Circulation 113(8), 1051–1052 (2006).

- Marino IR, ChapChap P, Esquivel CO et al. Liver transplantation for arteriohepatic dysplasia (Alagille’s syndrome). Transpl. Int. 5(2), 61–64 (1992).

- Png K, Veyckemans F, De Kock M et al. Hemodynamic changes in patients with Alagille’s syndrome during orthotopic liver transplantation. Anesth. Analg. 89(5), 1137–1142 (1999).

- Tzakis AG, Reyes J, Tepetes K, Tzoracoleftherakis V, Todo S, Starzl TE. Liver transplantation for Alagille’s syndrome. Arch. Surg. 128(3), 337–339 (1993).

- Bellsham-Revell HR, Tibby SM, Bell AJ et al. Serial magnetic resonance imaging in hypoplastic left heart syndrome gives valuable insight into ventricular and vascular adaptation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61(5), 561–570 (2013).

- Rhode KS, Sermesant M, Brogan D et al. A system for realtime XMR guided cardiovascular intervention. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 24(11), 1428–1440 (2005).

- Rhode KS, Hill DLG, Edwards PJ et al. Registration and tracking to integrate X-ray and MR images in an XMR facility. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 22(11), 1369–1378 (2003).

- Gutiérrez LF, Silva R de, Ozturk C et al. Technology preview: X-ray fused with magnetic resonance during invasive cardiovascular procedures. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 70(6), 773–782 (2007).

- George AK, Sonmez M, Lederman RJ, Faranesh AZ. Robust automatic rigid registration of MRI and x-ray using external fiducial markers for XFM-guided interventional procedures. Med. Phys. 38(1), 125–141 (2011).

- Vitiello R, McCrindle BW, Nykanen D, Freedom RM, Benson LN. Complications associated with pediatric cardiac catheterization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 32(5), 1433–1440 (1998).

- Cassidy SC, Schmidt KG, Van Hare GF, Stanger P, Teitel DF. Complications of pediatric cardiac catheterization: a 3-year study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 19(6), 1285–1293 (1992).

- Lin CH, Hegde S, Marshall AC et al. Incidence and management of life-threatening adverse events during cardiac catheterization for congenital heart disease. Pediatr. Cardiol. 35(1),140–148 (2013).

- Watson TG, Mah E, Joseph Schoepf U, King L, Huda W, Hlavacek AM. Effective radiation dose in computed tomographic angiography of the chest and diagnostic cardiac catheterization in pediatric patients. Pediatr. Cardiol. 34(3), 518–524 (2012).

- Rickers C, Kraitchman D, Fischer G, Kramer H-H, Wilke N, Jerosch-Herold M. Cardiovascular interventional MR imaging: a new road for therapy and repair in the heart. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 13(3), 465–479 (2005).

- Saikus CE, Lederman RJ. Interventional cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: a new opportunity for imageguided interventions. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2(11), 1321–1331 (2009).

- Lederman RJ. Cardiovascular interventional magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 112(19), 3009–3017 (2005).

- Moore P. MRI-guided congenital cardiac catheterization and intervention: the future? Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 66(1), 1–8 (2005).

- Lotz J. Interventional vascular MRI: moving forward. Eur. Heart J. 34(5), 327–329 (2013).

- Xiao B, Kakareka JW, Pursley RH, Pohida T, Lederman RJ, Faranesh A. MRI compatible hemodynamic recording system. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 15(Suppl. 1), P22 (2013).

- Sonmez M, Saikus CE, Bell JA et al. MRI active guidewire with an embeddedtemperature probe and providing a distinct tipsignal to enhance clinical safety. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 14(1), 1–1 (2012).

- Weiss S, Wirtz D, David B et al. In vivo evaluation and proof of radiofrequency safety of a novel diagnostic MR-electrophysiology catheter. Magn. Reson. Med. 65(3), 770–777 (2011).

- Rickers C, Jerosch-Herold M, Hu X et al. Magnetic resonance image-guided transcatheter closure of atrial septal defects. Circulation 107(1), 132–138 (2003).

- Schalla S, Saeed M, Higgins CB, Martin A, Weber O, Moore P. Magnetic resonance--guided cardiac catheterization in a swine model of atrial septal defect. Circulation 108(15), 1865–1870 (2003).

- Arepally A, Karmarkar PV, Weiss C, Rodriguez ER, Lederman RJ, Atalar E. Magnetic resonance image-guided trans-septal puncture in a swine heart. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 21(4), 463–467 (2005).

- Raval AN, Telep JD, Guttman MA et al. Real-time magnetic resonance imaging-guided stenting of aortic coarctation with commercially available catheter devices in Swine. Circulation 112(5), 699–706 (2005).

- Kuehne T, Yilmaz S, Meinus C et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided transcatheter implantation of a prosthetic valve in aortic valve position: feasibility study in swine. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44(11), 2247–2249 (2004).

- Krämer NA, Krüger S, Schmitz S et al. Preclinical evaluation of a novel fiber compound MR guidewire in vivo. Invest. Radiol. 44(7), 390–397 (2009).

- Muller L, Saeed M, Wilson MW, Hetts SW. Remote control catheter navigation: options for guidance under MRI. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 14, 33 (2012).

- Gosselin FP, Lalande V, Martel S. Characterization of the deflections of a catheter steered using a magnetic resonance imaging system. Med. Phys. 38(9), 4994–5002 (2011).

- Krings T, Finney J, Niggemann P et al. Magnetic versus manual guidewire manipulation in neuroradiology: in vitro results. Neuroradiology 48(6), 394–401 (2006).

- Losey AD, Lillaney P, Martin AJ et al. Magnetically assisted remote-controlled endovascular catheter for interventional MR imaging: in vitro navigation at 1.5 T versus x-ray fluoroscopy. Radiology 132041 (2014).

- Buckley PR, McKinley GH, Wilson TS et al. Inductively heated shape memory polymer for the magnetic actuation of medical devices. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 53(10), 2075–2083 (2006).

- Housden R, Arujuna A, Ma Y et al. Evaluation of a realtime hybrid three-dimensional echo and x-ray imaging system for guidance of cardiac catheterisation procedures. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. 15(Pt 2), 25–32 (2012).

- Gao G, Penney G, Ma Y et al. Registration of 3D transesophageal echocardiography to x-ray fluoroscopy using image-based probe tracking. Med. Image Anal. 16(1), 38–49 (2012).

- Peressutti D, Penney GP, Housden RJ et al. A novel Bayesian respiratory motion model to estimate and resolve uncertainty in image-guided cardiac interventions. Med. Image Anal. 17(4), 488–502 (2013).

- Faranesh AZ, Kellman P, Ratnayaka K, Lederman RJ. Integration of cardiac and respiratory motion into MRI roadmaps fused with x-ray. Med. Phys. 40(3), 032302 (2013).

- Vergara GR, Vijayakumar S, Kholmovski EG et al. Realtime magnetic resonance imaging-guided radiofrequency atrial ablation and visualization of lesion formation at 3 Tesla. Heart Rhythm 8(2), 295–303 (2011).

- Hoffmann BA, Koops A, Rostock T et al. Interactive realtime mapping and catheter ablation of the cavotricuspid isthmus guided by magnetic resonance imaging in a porcine model. Eur. Heart J. 31(4), 450–456 (2010).

- Koopmann M, Marrouche NF. Why hesitate introducing real-time magnetic resonance imaging into the electrophysiological labs? Europace 15(1), 7–8 (2013).

- Lederman RJ, Guttman MA, Peters DC et al. Catheterbased endomyocardial injection with real-time magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 105(11), 1282–1284 (2002).

- Hill JM, Dick AJ, Raman VK et al. Serial cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of injected mesenchymal stem cells. Circulation 108(8), 1009–1014 (2003).

- Dicks D, Saloner D, Martin A, Carlsson M, Saeed M. Percutaneous transendocardial VEGF gene therapy: MRI guided delivery and characterization of 3D myocardial strain. Inter. J. Cardiol. 143(3), 255–263 (2010).