Review Article - Interventional Cardiology (2022) Volume 14, Issue 2

Cardiovascular diseases as major extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection: Leukocytes, not hepatocytes, are the targets of hepatitis C virus infection

- Corresponding Author:

- Akira Matsumori

Clinical Research Center,

Kyoto Medical Center 1-1 Fukakusa Mukaihata-cho,

Fushimi-ku,

Kyoto 612-8555,

Japan,

E-mail: amat@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp

Received date: 15-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. FMIC-22-57308; Editor assigned: 17-Mar-2022, PreQC No. FMIC-22-57308 (PQ); Reviewed date: 31-Mar-2022, QC No. FMIC-22-57308; Revised date: 04-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. FMIC-22-57308 (R); Published date: 11-Apr-2022, DOI: 10.37532/1755- 5310.2022.14(2).472

Abstract

Almost all viruses cause cardiovascular diseases, and coxsackievirus and influenza virus are thought to be the most common causes of acute myocardial injuries. On the other hand, Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) usually causes chronic myocardial damage. HCV is the cause of many different forms of heart disease worldwide, but few cardiologists are aware of its etiology in heart disease or how to treat it. HCV causes heart failure with both reduced and preserved ejection fraction, such as myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. HCV also causes various arrhythmias, conduction disturbances, and QT prolongation. Cardiac troponins, N-Terminal pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NTproBNP), and immunoglobulin free light chains are good biomarkers of cardiovascular diseases in HCV-positive patients. It is known that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory process, and HCV infection may be an important risk factor for atherosclerosis.

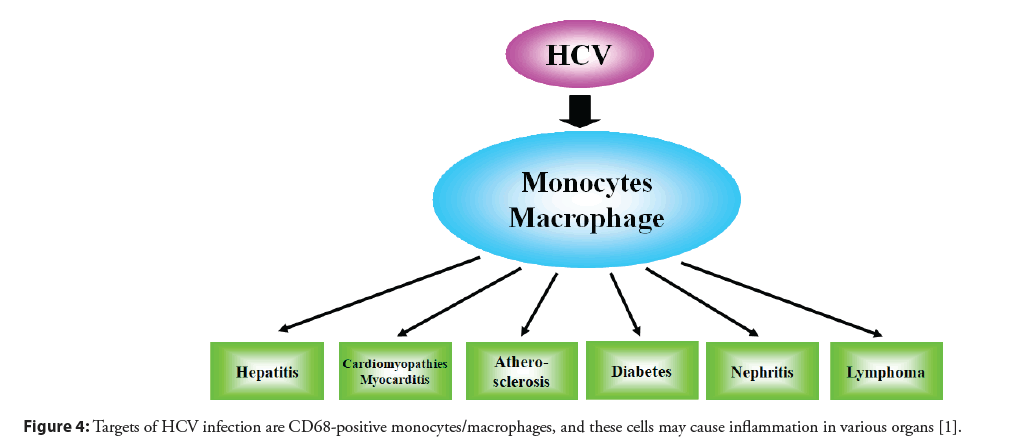

We found that HCV infects mononuclear cells, and that the target of HCV infection is mononuclear cells, not hepatocytes. Infected monocytes and macrophages cause chronic persistent inflammation, and this inflammatory reaction can cause various types of organ damage as well as myocyte necrosis, fibrosis, and myocyte hypertrophy in the heart. The diverse clinical biology of HCV and the presence of multiple extrahepatic disease syndromes can be explained by the effect of HCV-infected mononuclear cells in the bone marrow and the viral modulation of host immune responses. It was suggested that CD68 monocytes/macrophages are the major targets of HCV, and pharmacologic preparations targeting leukocyte infection can be used to treat HCV. New therapeutic trials of HCV infections including cardiovascular diseases will be needed based on the new hypothesis that the target of HCV infection is mononuclear cells. In addition to anti-HCV agents, cytapheresis and anti-inflammatory therapy by anti-histaminic agents and pycnogenol show promise. The aim of this review is to evaluate the evidence that HCV causes various cardiovascular diseases, and discuss on the pathogenesis of these disorders.

Keywords

Arrhythmias • Atherosclerosis • Cardiomyopathy • Heart failure • Hepatitis C virus • Inflammation • Immunoglobulins • Leukocytes • Mononuclear cells • Myocarditis

Introduction

Almost all viruses cause cardiovascular diseases, but coxsackievirus and influenza virus are thought to be the most common causes of acute myocardial injuries. On the other hand, Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) usually causes chronic myocardial damage. Coronaviruses commonly cause diseases in animals, and while there were a few reports of myocarditis and cardiomyopathy caused by this virus in humans prior to the 2020 pandemic, myocardial abnormalities have been seen frequently in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 [1]. Enteroviruses, such as coxsackievirus, echovirus, and poliovirus, as well as the influenza virus, can cause myocyte necrosis directly, and acute myocarditis follows myocyte injury. In cases with severe myocardial injury, cardiac fibrosis replaces injured myocytes, which leads to persistent cardiac dysfunction, and the remaining myocytes develop compensatory hypertrophy [1,2]. The genomes of enteroviruses such as coxsackieviruses, parvovirus B19, human herpesvirus 6, adenoviruses, Epstein–Barr virus, human cytomegalovirus, and human immunodeficiency virus have been detected in endomyocardial biopsy specimens in human myocarditis and cardiomyopathy [3-7]. However, the presence of a viral genome does not necessarily show the cause of the disease; inflammatory and/or immune responses are required to develop myocarditis.

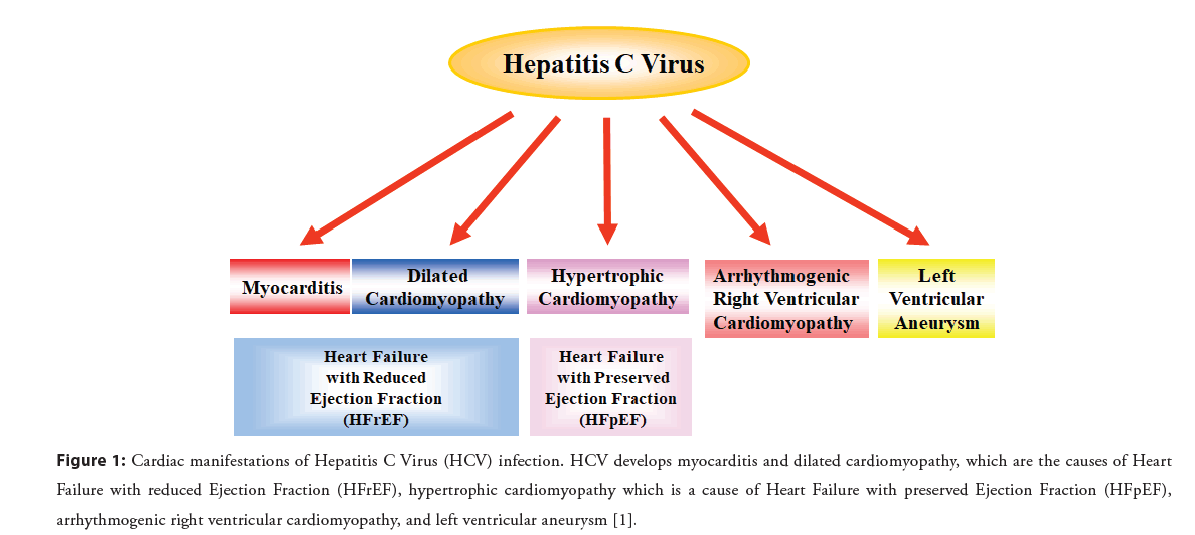

HCV is the cause of many different forms of heart disease worldwide, yet few cardiologists are aware of its etiology in heart disease or how to treat it. HCV infection is seen globally, but it is often undetected and, therefore, untreated. The burden of HCVderived heart diseases is global, with a higher prevalence in Asia, Africa, and low and middle income countries. HCV-derived heart diseases are chronic, persistent, and devastating [8]. An estimated 71 million people worldwide have chronic HCV infection, and there are 350,000 liver-related deaths per year. There is considerable evidence showing that HCV infection is a nontraditional and modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Observational studies have shown an increased prevalence of HCV infection in patients with cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, heart failure, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, or stroke (Figure 1) [1,2,9,10].

Figure 1: Cardiac manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection. HCV develops myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy, which are the causes of Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy which is a cause of Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, and left ventricular aneurysm [1].

We found that HCV infects mononuclear cells, and the target of infection is mononuclear cells, not hepatocytes. This evidence may explain why HCV causes extrahepatic manifestations of various organs [11]. In this review, the role of HCV infection in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, is discussed.

Literature Review

Cardiovascular diseases in patients with HCV infection

Our previous collaborative research was conducted to investigate the role of HCV infection in cardiovascular diseases in Japan. HCV antibody was detected in in 650 of 11,967 patients (5.4%) seeking care at five academic hospitals. Various cardiovascular abnormalities were found, such as arrhythmias, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and heart failure (Table 1) [12]. HCV antibody was found in 6.6% of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cases and 6.3% of dilated cardiomyopathy cases; these prevalence rates were significantly higher compared to the rates in volunteer blood donors. These observations suggest that HCV infection is an important cause of a variety of otherwise unexplained heart diseases. In addition, this study also suggests that HCV infection might have a pathogenetic role in diabetes mellitus and renal diseases (Table 1) [12].

| Clinical diagnosis | n | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmias | 75 | 21.5 |

| Hypertension | 71 | 20.3 |

| Myocardial infarction | 57 | 16.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 50 | 14.3 |

| Angina pectoris | 45 | 12.9 |

| Renal disease | 41 | 11.7 |

| Valvular heart diseases | 33 | 9.5 |

| Congestive heart failure | 28 | 8 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 23 | 6.6 |

| Post valvular replacement and/or CABG | 22 | 6.3 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 20 | 5.7 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7 | 2 |

| Unclassified cardiomyopathy | 2 | 0.6 |

| Myocarditis | 1 | 0.3 |

Table 1: Clinical diagnosis of patients with positive Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) antibody. Adapted from [12].

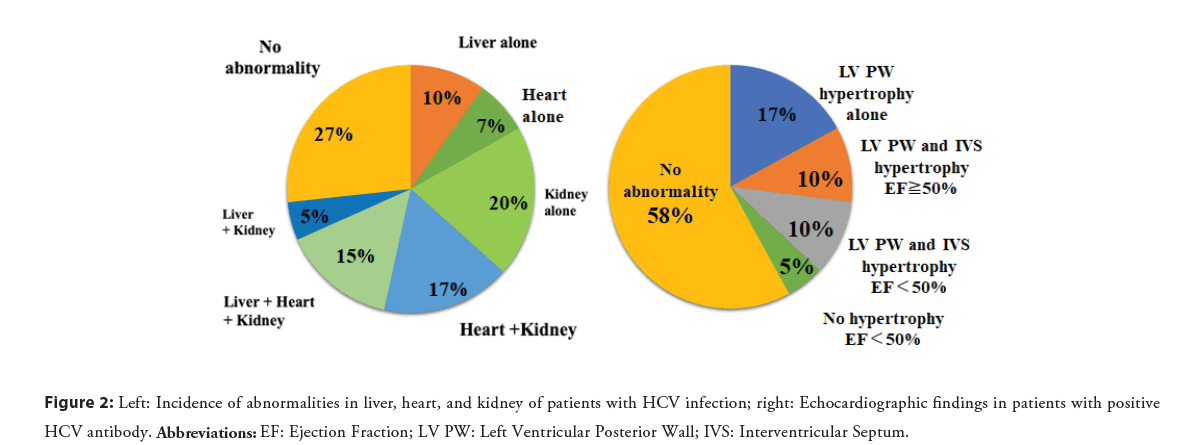

We analyzed 186 patients with positive HCV antibody at a hospital in Japan to detect the presence or absence of hepatic, renal, or cardiac abnormalities. Liver abnormality was defined as elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST), renal abnormality as estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR)<60 mL/min, and cardiac abnormality as increased left ventricular wall thickness>10 mm or Ejection Fraction (EF)<50% on echocardiography. Liver abnormality was identified in 30% of patients, renal abnormality in 38%, both abnormalities in 15%, and no abnormality in 47%, based on laboratory testing. Echocardiography was performed on 41 of the 186 patients, which identified liver abnormality in 30%, renal abnormality in 57%, cardiac abnormality in 39%, involvement of all three organs in 15%, and no abnormality in 27%. Increased left ventricular wall thickness was found in 37%, left ventricular posterior wall thickness in 27%, left ventricular posterior wall and interventricular septal hypertrophy in 20%, and decreased ejection fraction in 15%. Among the patients, 10% exhibited both left ventricular hypertrophy and decreased ejection fraction (Figure 2) [13]. This study demonstrates that HCV infection frequently causes cardiac and renal abnormalities. Various types of cardiomyopathy were found, but cardiac hypertrophy was the most common manifestation of cardiac abnormality, and left ventricular posterior wall hypertrophy was the most frequent. Thus, HCV infection may be an important cause of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy.

HCV infection in heart diseases

Our study shows that cardiomyopathy is associated with HCV infection in more than 10% of Japanese patients, and up to 15% patients with heart failure with myocarditis in the USA have HCV infection [8,14]. In contrast, 16 to 38% of HCV-positive patients in China and 17% of such patients in Pakistan have heart disease, as measured by, N-Terminal pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP), a biomarker of heart disease (Table 2) [8,15-17]. HCV infection has also been associated with pericarditis [18,19], Arrythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC) [8], left ventricular aneurysm [20], QT prolongation [21], conduction disturbances, and various arrhythmias (Figure 1) [22].

| Authors, Reference | Patients (N) | Clinical Manifestation | NT-proBNP | Electrocardiographic or echocardiographic Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated | Values (pg/mL) | |||||

| N (%) | Patients | Controls | ||||

| Matsumori, et al. [8] | 547 | HCV antibody+ | 84 (17%) | |||

| Wang, et al. [15] | 151 | HCV Hepatitis | 58 (38%) | 347 (mean) | 22 | |

| Saleh, et al. [16] | 30 | HCV Hepatitis | 222 (mean) | 21 | QTc prolongation LV diastolic dysfunction | |

| Che, et al. [17] | 90 | HCV antibody+ | 14 (16%) | 62 (median) | 17 | LV diastolic dysfunction |

Abbreviation: LV: Left

Table 2: Circulating NT-proBNP in patients with antibody against HCV and patients with HCV hepatitis.

HCV antigens and RNA in heart tissue

It is important to detect viral antigens and genomes in the tissues to confirm their role in pathogenesis. In an initial study, by polymerase chain reaction, we found HCV RNA in the hearts of 17% of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, compared to 2.5% of patients with ischemic heart disease. (Table 3) [23]. The main clinical manifestations were heart failure and arrhythmias. Both positive and negative strands of HCV RNA were detected in the hearts of some patients [23]. Because negative RNA is an intermediate in the replication of the HCV genome, the presence of negative strands suggests that HCV replicates in myocardial tissues. We also found that 17% of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy had evidence of HCV infection (Table 3). None of these patients had a family history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was diagnosed in 8% of patients who had ace-of-spades-shaped deformities of the left ventricle. Histopathologic studies showed mild to severe myocyte hypertrophy in the right or left ventricle, mild to moderate fibrosis, and mild cellular infiltration [24]. An association with HCV infection was also reported in 23% of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a prevalence rate significantly higher compared to controls [25].

| Authors, Reference | Patients (N) | Diagnosis | HCV | HCV in the Heart | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody | Serum RNA | +Strands | -Strands | ||||

| Matsumori, et al. [23] | 36 | DCM | 6 (17%) | 4 (11%) | 3 | 1 | Biopsy |

| Matsumori, et al. [24] | 35 | HCM | 6 (17%) | 3 (9%) | 4 | Biopsy | |

| Matsumori, et al. [26] | 14 | Myocarditis | 4 (33%) | Autopsy | |||

| 42 | HCM | 6 (26%) | IHD 0% | ||||

| 50 | DCM | 3 (12%) | Autopsy | ||||

| Matsumori, et al. [8] | 16 | DCM | 4 (25%) | 4 | |||

| 6 | ARVC | 2 (33%) | |||||

| Matsumori, et al. [14] | 1355 | Myocarditis | 59 (4.4%) | Control 1.8% Elevated cTnT 45% Elevated NT-proBNP 100% | |||

Abbreviations: ARVC: Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy; DCM: Dilated Cardiomyopathy; HCM: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy; IHD: Ischemic Heart Disease; cTnT: cardiac troponin T

Table 3: Circulating Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) RNA and antibody against HCV, and HCV genomes in the hearts of patients with cardiomyopathies and myocarditis.

We detected HCV RNA in 33% of autopsied hearts from patients with myocarditis, 26% from patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and 12% from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (Table 3) [26]. We also examined autopsied hearts from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy in a collaborative study with the University of Utah and found HCV RNA in 35% of the hearts. The sequences of HCV genome recovered from these hearts were highly homologous to the standard strain of HCV [26]. However, the rates of HCV genome detection in the hearts of patients with cardiomyopathy varied widely in different regions of the world. For example, no HCV genome was detected in hearts obtained from a hospital in Vancouver, Canada. These observations suggest that the frequency of cardiomyopathy caused by HCV infection may differ across regions or among different populations. A multicenter study by the Scientific Council on Cardiomyopathy of the World Heart Federation found the HCV genome in 18% of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and myocarditis in Italy and in 36% in the United States, two from patients with myocarditis and two with ARVC [8], which suggests that HCV may cause ARVC.

We analyzed sera stored during the US Myocarditis Treatment Trial of immunosuppression in patients with heart failure and myocarditis which was conducted by Mason and coworkers [27]. Anti-HCV antibodies were identified in 4.4% of patients, including 5.9% of patients with biopsy-proven myocarditis. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the prevalence of HCV infection in the general US population is 1.8%, thus it is more prevalent in patients with heart failure because of myocarditis (Table 3) [14].

Discussion

Leukocytes, not hepatocytes, are the targets of HCV infection: A new concept of pathogenesis of HCV-induced diseases

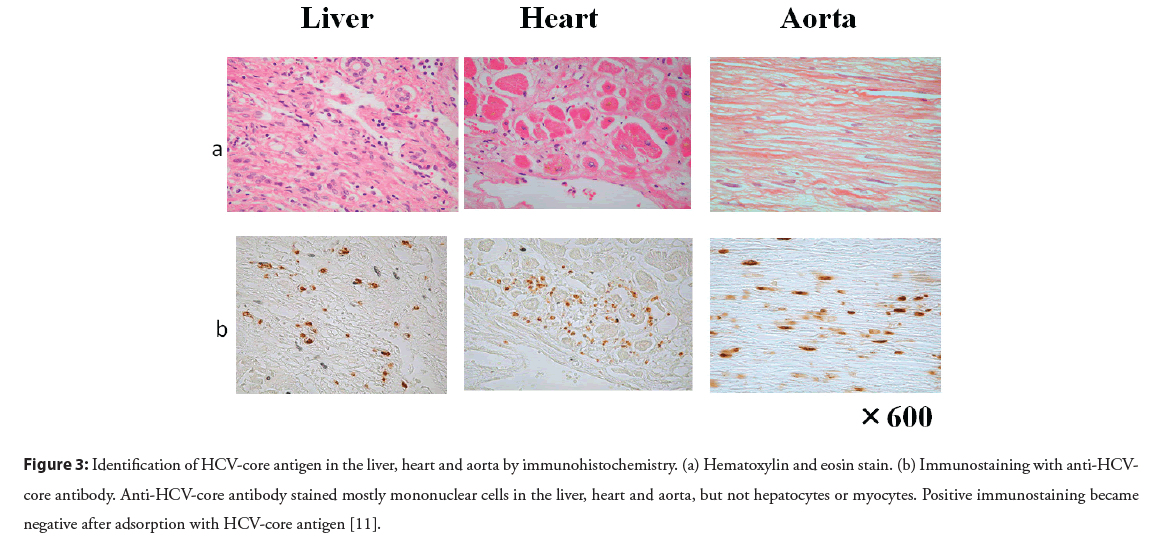

The pathogenetic mechanisms of multiple extrahepatic diseases remain to be clarified. Immunohistochemistry has been used to detect HCV antigens, but the results have been controversial. Our study clearly demonstrates the localization of HCV antigens in various paraffin-embedded tissues. Antibody against HCV core antigen stained Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs), and the majority of positive staining was seen in CD68-positive monocytes/macrophages [11]. HCV core antibody stained mostly mononuclear cells in the liver, heart, aorta, kidney, and bone marrow, but not hepatocytes or myocytes (Figure 3). Positive staining was found in PBMCs and mononuclear cells of various tissues by antibody against non-structural NS4 protein, which also supports the probability that HCV replicates in mononuclear cells. Therefore, mononuclear cells may be a primary target of HCV infection (Figure 4) [11]. The notion that HCV is a lymphotropic virus is supported by findings of replicating HCV found in B cells [28], T cells [29], and PBMCs from patients with chronic hepatitis C [30].

Figure 3: Identification of HCV-core antigen in the liver, heart and aorta by immunohistochemistry. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin stain. (b) Immunostaining with anti-HCVcore antibody. Anti-HCV-core antibody stained mostly mononuclear cells in the liver, heart and aorta, but not hepatocytes or myocytes. Positive immunostaining became negative after adsorption with HCV-core antigen [11].

Figure 4: Targets of HCV infection are CD68-positive monocytes/macrophages, and these cells may cause inflammation in various organs [1].

New biomarkers of viral myocarditis: Immunoglobulin free light chains

Immunoglobulin Free Light Chains (FLCs) are synthesized de novo and secreted into the circulation by B cells and plasma cells. As FLCs are an excess byproduct of antibody synthesis by these cells, an elevated FLC level has been proposed as a biomarker of B cell activity in many inflammatory and autoimmune conditions [31]. Polyclonal FLCs are reported to be a predictor of mortality in the general population, as measured by the sum of κ and λ concentrations [32].

Previously, our group observed that FLCs were increased in a mouse model of heart failure due to Encephalomyocarditis (EMC) virus myocarditis [33]. Recently, we conducted additional research on patients in heart failure, and observed that circulating FLC λ was increased while the κ/λ ratio was decreased in sera from patients with heart failure resulting from myocarditis compared to a group of healthy controls. These findings demonstrate that FLC λ and the κ/λ ratio together show good diagnostic potential for the identification of myocarditis. In addition, the FLC κ/λ ratio can also be used as an independent prognostic factor for overall patient survival [34].

High concentrations of FLC κ have been observed in HCVpositive patients, and alterations in the κ/λ ratio have been positively correlated with increasing severity of HCV-related lymphoproliferative disorder [35]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the κ/λ ratio may be useful in evaluating therapeutic efficacy [36]. In our study on FLCs using sera from the multicenter US Myocarditis Treatment Trial, myocardial injury was found to be more severe in patients with HCV infection than in noninfected patients. The level of FLC κ was lower, FLC λ was higher, and the κ/λ ratio was decreased in patients with myocarditis, both with and without biopsy confirmation according to the Dallas criteria, compared to normal volunteers. These changes were more prominent in patients with HCV infection than those without infection. HCV infection may enhance the production of FLC λ while decreasing FLC κ [1,37]. Although the mechanisms of these changes require clarification, detection of FLCs might be helpful in diagnosing myocarditis with heart failure and useful in differentiating patients with HCV infection from those without infection. In heart failure patients, left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters, pulmonary arterial pressure, and NTproBNP were correlated positively with FLC λ and negatively with the κ/λ ratio. Left ventricular EF was also negatively correlated with the κ/λ ratio [37].

HCV and atherosclerosis

An association between HCV infection and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events was shown by meta-analysis [9,38], and the incidence of cardiovascular events was higher in patients with HCV RNA than in those without, suggesting that active HCV infection increases the risk of cardiovascular events [39]. An increased risk of carotid intima-media thickening and plaques was shown [40], and HCV infection was shown to be an independent risk factor for stroke [41,42]. The risk of coronary artery disease was increased and the incidence of acute coronary syndrome was significantly higher in patients with HCV infection than those without infection [43,44]. HCV-infected patients were shown to have an increased risk of death from cardiovascular causes compared to matched uninfected blood donors [38]. As discussed above, accumulating evidence shows an association between HCV infection and atherosclerosis, but the mechanism by which HCV is involved in atherosclerosis remains to be clarified. Chronic HCV infection induces a proinflammatory state due to overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 and pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased oxidative stress, and immune stimulation, leading to endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, and, finally, cardiovascular disease [45]. HCV infection causes insulin resistance associated with endothelial dysfunction, persistent inflammation, and lipid imbalance, leading to atherosclerosis [46].

HCV RNA has been detected in atherosclerotic plaques in carotid arteries, suggesting the direct effect of HCV on atherosclerotic plaque formation by local inflammation [47]. However, since this study was conducted by polymerase chain reaction, it does not show what cells HCV localizes. Localization of HCV RNA should be demonstrated by in situ hybridization and HCV antigen proteins shown by immunohistochemistry. Since we have shown that HCV antigen proteins exist in mononuclear cells, it follows that HCVinfected mononuclear cells may cause inflammation in arteries and lead to the development of atherosclerosis. Furthermore, HCV infection has been shown to induce endothelial dysfunction which is the earliest event in the atherosclerotic process [48].

Treatment trials of HCV cardiomyopathy and myocarditis

We examined the effects of interferon on myocardial injury associated with active HCV hepatitis using TL-201 Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) imaging, because it is more sensitive than electrocardiography or echocardiography in detecting myocardial injury induced by HCV [8]. The SPECT scores decreased for more than half of the patients who completed interferon treatment. Circulating HCV disappeared after interferon therapy in all patients who showed either a decrease or no change in SPECT scores, and the HCV genome persisted in the blood of patients whose clinical status worsened [8]. This preliminary study suggests that interferon is a promising treatment for myocardial disease caused by HCV. We also reported the benefits of treatment with interferon guided by serial measurement of serum HCV RNA and cardiac troponin T in a patient who presented with dilated cardiomyopathy and striated myopathy attributable to HCV infection [8].

Haykal and coworkers studied anti-inflammatory therapy with cetirizine in patients with HCV heart failure, which was reported to be effective in animal models of viral myocarditis [1], and showed that myocardial function was substantially improved in patients who took cetirizine [22]. There was a significant decrease in global left ventricular average strain and a significant increase in left ventricular ejection fraction.

Anti-viral effects of pycnogenol on HCV

Pycnogenol (PYC), a natural plant extract derived from the bark of the French maritime pine (Pinus pinaster, subsp. atlantica), is a highly concentrated source of flavanols as well as phenolic and cinnamic acids [49]. In a previous study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory properties of PYC in a murine model of viral myocarditis. The results showed that PYC inhibited EMC virus replication both in vitro and in vivo in animals, improved inflammation, and preserved myocardial tissue by decreasing necrosis [50]. PYC showed antiviral effects against HCV and synergistic effects with interferon (IFN)-α or ribavirin in vitro [51]. PYC was found to work additively with the antiviral preparation telaprevir to reduce the levels of HCV RNA in wildtype HCV replicon cells. Further, PYC was also shown to inhibit viral replication in telaprevir-resistant replicon cells. In vivo investigations of HCV-infected chimeric mice revealed that PYC again inhibited HCV replication. Further, the extract showed a synergistic antiviral effect with IFN-α, and the addition of PYC to HCV replicon cell lines resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in reactive oxygen species [51].

We performed a double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trial with patients with Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), and found that circulating HBV was reduced and hepatic function was improved in PYC group [1]. Since PYC has broad-spectrum antiviral effects against several viruses in vitro and in vivo, as well as antiinflammatory effects against many inflammatory diseases, it is a promising agent for the prevention and treatment of viral diseases in humans.

Cytapheresis therapy for HCV diseases

Based on our hypothesis that mononuclear cells are the target of HCV infection, we performed a cytapheresis experiment on peripheral blood from HCV-positive patients using a filter of syndiotactic polystyrene resin sheets with hydroxypropyl cellulose and cellulose acetate. HCV core antigens were decreased by 59%, 57%, and 77% in whole blood, sera, and mononuclear cells, respectively, after perfusion compared to before perfusion [52]. Since mononuclear cells supposedly carry HCV to various organs, this method may be able to remove mononuclear leukocytes and be useful for the treatment of HCV-related disorders, especially for patients who are undergoing hemodialysis therapy.

Direct-acting antiviral therapy and cardiovascular diseases

Treatment with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and interferon or Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) therapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of a cardiovascular event compared with controls [53]. Recent studies evaluating the impact of HCV clearance by DAA on carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases indirectly confirmed the fundamental role of HCV in the development of these diseases [10]. Prospective studies have shown that the elimination of HCV causes a significant improvement in carotid atherosclerosis [54], and that HCV clearance is associated with a significant decrease in the relative risk of developing cardiovascular disease, with an annual incident rate reduction of 68% [55]. A large retrospective study showed a reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular disease of 16.3 per 1000 patient-years and a lower risk of cardiovascular events after HCV clearance by DAAs [54].

New therapeutic trials of HCV infections, including HCV cardiovascular diseases, will be needed based on the new hypothesis that the target of HCV infection is mononuclear cells. As we showed previously, anti-inflammatory agents that do not have antiviral effects improved viral myocardial injury [1]. Therefore, combined therapy with antiviral and anti-inflammatory agents could potentially be used as treatment for HCV cardiovascular diseases.

Conclusion

HCV causes heart failure, with both reduced and preserved ejection fraction, such as myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. HCV also causes various arrhythmias, conduction disturbances, and QT prolongation. In addition, HCV infection may be an important risk factor for atherosclerosis. Cardiac troponins, NT-proBNP, and FLCs are good biomarkers of HCV heart disease. We found that HCV infects mononuclear cells, and that the target of infection is mononuclear cells, not hepatocytes. The diverse clinical biology of HCV and the presence of multiple extrahepatic disease syndromes can be explained by the effect of HCV-infected mononuclear cells. New therapeutic trials of HCV infections, including HCV cardiovascular diseases, will be needed based on the new hypothesis that the target of HCV infection is mononuclear cells. In addition to anti-HCV agents, combined therapy with antiviral and anti-inflammatory agents could potentially be used as treatment for HCV cardiovascular diseases.

References

- Matsumori A. Viral myocarditis from animal models to human diseases. In Berhardt LV, editor. Advances in medicine and biology. New York. Nova Science Publishers. Inc. 194: 41-74 (2022).

- Matsumori A. Cardiomyopathies and heart failure. In Matsumori A, editor. Cardiomyopathies and heart failure. Developments in cardiovascular medicine. Boston. Springer. 248: 1-15 (2003).

- Pollack A, Kontorovich AR, Fuster V, et al. Viral myocarditis-diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 12(11): 670-680 (2015).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schultheiss H-P, Fairweather D, Caforio ALP, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathies. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5(1): 32 (2019).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tschope C, Ammirai E, Bozkurt B, et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: Current evidence and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 18(3): 169-193 (2021).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooper LT. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 360(15): 1526-1538 (2009).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A. Animal models: Pathologic findings and therapeutic considerations. In Banatvala JE, editor. Viral infections of the heart. London. Edward Arnold. pp 110-137 (1993).

- Matsumori A. Global alert and response network for hepatitis C virus-derived heart diseases: A call to action. Global Heart. 4: 109-118 (2009).

- Cacoub, P, Saadoun D. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 384(11): 1038-1052 (2021).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mazzaro C, Quartuccio L, Adinolfi LE, et al. A review on extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis c virus infection and the impact of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Viruses. 13(11): 2249 (2021).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A, Shimada M, Obata T. Leukocytes are the major target of hepatitis C virus infection: Possible mechanism of multiorgan involvement including the heart. Global Heart. 5(2): 51-58 (2010).

- Matsumori A, Ohashi N, Hasegawa K, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and heart diseases: A multicenter study in Japan. Jpn Circ J. 62(5): 389-391 (1998).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A, Ishitani H, Otani H, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection as a cause of cardiomyopathies and nephritis. International Society of Cardiomyopathies and Heart Failure Congress, December 2, Kyoto. Abstract (2016).

- Matsumori A, Shimada T, Chapman NM, et al. Myocarditis and heart failure associated with hepatitis C virus infection. J Card Fail. 12(4): 293-298 (2006).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Geng J, Li J, et al. The biomarker N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and liver diseases. Clin Invest Med. 34(1): E30-37 (2011).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saleh A, Matsumori A, Negm H, et al. Assessment of cardiac involvement of hepatitis C virus; tissue doppler imaging and NTproBNP study. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 23(4): 217-223 (2011).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Che W, Liu W, Wei Y, et al. Increased serum N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and left ventricle diastolic dysfunction in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 19(5): 327-331 (2012).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rombola F, Spinoso A, Bertuccio SN. Cardiac manifestations during viral acute hepatitis. Infez Med. 14(1): 29-32 (2006).

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bertuccio SN, Rombola F, Bertuccio A, et al. HCV infection and pericarditis: An extrahepatic manifestation? Infez Med. 13(1): 42-44 (2005).

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chimenti C, Calabrese F, Thiene G, et al. Inflammatory left ventricular microaneurysms as a cause of apparently idiopathic ventricular tachy-arrhythmias. Circulation. 104(2): 168-173 (2001).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nordin C, Kohli A, Beca S, et al. Importance of hepatitis C co-infection in the development of QT prolongation in HIV-infected patients. J Electrocardiol. 39(2): 199-205 (2006).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haykal M, Matsumori A, Saleh A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of HCV heart diseases. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 19(6): 493-499 (2021).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A, Matoba Y, Sasayama S. Dilated cardiomyopathy associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Circulation 92(9): 2519-2525 (1995).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A, Matoba Y, Nishio R, et al. Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA from the heart of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 222(3): 678-82 (1996).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Teragaki M, Nishiguchi S, Takeuchi K, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart Vessels. 18(4): 167-170 (2003).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A, Yutani C, Ikeda Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus from the hearts of patients with myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Lab Invest. 80: 1137-1142 (2000).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mason JW, O’Connell JB, Herskowitz A, et al. A clinical trial of immuno-suppressive therapy for myocarditis. The Myocarditis Treatment Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 333(5): 269-275 (1995).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pal S, Sullivan DG, Kim S, et al. Productive replication of hepatitis C virus in perihepatic lymph nodes in vivo: Implications of HCV lymphotropism. Gastroenterology 130(4): 1107-1116 (2006).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MacParland SA, Pham TN, Gujar SA, et al. De novo infection and propagation of wild-type hepatitis C virus in human T lymphocytes in vitro. J Gen Virol. 87(Pt 12): 3577-3586 (2006).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, et al. Positive and negative strand of hepatitis C virus RNA sequences in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C: No correlation with viral genotypes 1b, 2a, and 2b. J Med Virol. 52(3): 270-274 (1997).

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hampson J, Turner ARS. Polyclonal free light chains: Promising new biomarkers in inflammatory disease. Current Biomarker Findings. 4: 139-149 (2014).

- Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, et al. Use of nonclonal serum immunoglobulin free light chains to predict overall survival in the general population. Mayo Clin Proc. 87(6): 517-523 (2012).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A, Shimada M, Jie X, et al. Effects of free immunoglobulin light chains on viral myocarditis. Circ Res. 106(9): 1533-1540 (2010).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumori A, Shimada T, Nakatani E, et al. Immunoglobulin free light chains as an inflammatory biomarker of heart failure with myocarditis. Clin Immunol. 217: 108455 (2020).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terrier B, Sène D, Saadoun D, et al. Serum-free light chain assessment in hepatitis C virus-related lymphoproliferative disorders. Ann Rheum Dis. 68(1): 89-93 (2009).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basile U, Gragnani L, Piluso A, et al. Assessment of free light chains in HCV positive patients with mixed cryoglobulinaemia vasculitis undergoing rituximab treatment. Liver Int. 35(9): 2100-2107 (2015).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] (All versions) [PubMed]

- Matsumori A. Novel biomarkers for diagnosis and management of myocarditis and heart failure: Immunoglobulin free light chains. 21st Century Cardiol. 2(1): 114 (2021)

- Petta S, Maida M, Macaluso FS, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Gastroenterology 150(1): 145-155.e4 (2016).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pothineni NVKC, Delongchamp R, Vallurupalli S, et al. Impact of hepatitis seropositivity on the risk of coronary heart disease events. Am J Cardiol. 114(12): 1841-1845 (2014).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Takahashi E, et al. Association between hepatitis C virus seropositivity, carotid-artery plaque, and intima-media thickening. Lancet. 359: 133-135 (2002).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adinolfi LE, Restivo L, Guerrera B, et al. Chronic HCV infection is a risk factor of ischemic stroke. Atherosclerosis. 231(1): 22-26 (2013).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee M-H, Yang H-I, Wang C-H, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and increased risk of cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 41: 2894-900 (2010).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Butt AA, Xiaoqiang W, Budoff M, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and the risk of coronary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 49: 225-232 (2009).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsai M-S, Hsu Y-C, Yu P-C, et al. Long-term risk of acute coronary syndrome in hepatitis C virus infected patients without antiviral treatment: A cohort study from an endemic area. Int J Cardiol. 181: 27-29 (2015).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Babiker A, Jeudy J, Kligerman S, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease due to chronic hepatitis C infection: A review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 5(4): 343-362 (2017).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, et al. Differences and similarities in early atherosclerosis between patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and chronic hepatitis B and C. J Hepatol. 46:1126-1132 (2007).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boddi M, Abbate R, Chellini B, et al. Hepatitis C virus RNA localization in human carotid plaques. J Clin Virol. 47: 72-75 (2010).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barone M, Viggiani MT, Amoruso A, et al. Endothelial dysfunction correlates with liver fibrosis in chronic HCV infection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015: 682174 (2015).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodewald PJ. Update on the clinical pharmacology of Pycnogenol. Med Res Arch. (2015).

- Matsumori A, Higuchi H, Shimada M. French maritime pine bark extract inhibits viral replication and prevents development of viral myocarditis. J Card Fail. 13(9): 785-791(2007).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ezzikouri S, Nishimura T, Kohara M, et al. Inhibitory effects of pycnogenol on hepatitis C virus replication. Antiviral Res. 113: 93-102 (2015).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kotera H, Fueda Y, Matsumori A. Development of a leukocyte removal filter for hepatitis C therapy and the possibility of multipurpose treatment. International Society of Cardiomyopathy, Myocarditis and Heart Failure Congress. 2021, Kyoto, Japan Abstract. (2021).

- Butt AA, Yan P, Shuaib A, et al. Direct-acting antiviral therapy for HCV infection is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease events. Gastroenterology. 156(4):987-996 (2019).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petta S, Adinolfi LE, Fracanzani AL, et al. Hepatitis C virus eradication by direct-acting antiviral agents improves carotid atherosclerosis in patients with severe liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 69(1): 18-24 (2018).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adinolfi LE, Petta S, Fracanzani AL, et al. Impact of hepatitis C virus clearance by direct-acting antiviral treatment on the incidence of major cardiovascular events: A prospective multicentre study. Atherosclerosis. 296: 40-47(2020).

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]