Case Series - International Journal of Clinical Rheumatology (2021) Volume 16, Issue 4

Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis: report of thirteen cases

- *Corresponding Author:

- Daniela G. P. Piotto

Division of Rheumatology and Unit of Pediatric Rheumatology - Department of Pediatrics

E-mail: danielapetry@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis (CNO), also known as Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO), is a rare autoinflammatory bone disorder that causes multifocal or unifocal aseptic lytic lesions in bone biopsy and is characterized by periodic exacerbations and remissions of sterile osteomyelitis. The aim of this report was to describe clinical features, subsidiary exams, treatment and outcome of thirteen cases of CNO followed in a tertiary center in Brazil.

Methods: We carried out a single-center retrospective descriptive review of clinical records, including thirteen children and adolescents with CNO followed between 2010 and 2020 in our tertiary service in Brazil. Medical records were reviewed in order to collect data about clinical presentation, inflammatory markers, radiological and histological findings, treatment and outcome.The diagnosis of CNO was based on the Bristol diagnostic criteria for CRMO.

Results: Thirteen patients were included in this study, of whom 46% were female. Median of current age and of follow-up time were 11 years (range 8.5-20.4) and 40 months (range 9-123), respectively. Median age at disease onset was 8.1 years (range 0.8–15.3) and median age at diagnosis was 11 years (range 7-16.1). The most affected sites were metaphysis and diaphysis of long bones. Median number of initially affected bones was 4.0 (range 1-7). Five patients had recurrences. All patients had increased acute phase reactants at disease onset. All patients had at least one of the characteristic findings on MRI (lytic lesions, osteitis, hyperostosis and periostitis). Five patients received systemic glucocorticoids, eight received methotrexate and seven received bisphosphonates (alendronate).

Conclusion: The awareness of the features of CNO is important for an early diagnosis and may avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures and prolonged antibiotic therapies.

Keywords

autoinflammatory disease • chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis • chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis • bone pain • children • adolescents

Introduction

Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis (CNO), also known as Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO), is an autoinflammatory bone disorder that presents multifocal or unifocal aseptic lytic lesions in bone biopsy and is characterized by periodic exacerbations and remissions of sterile osteomyelitis [1]. The term CRMO usually refers to the phenotype that evolves to relapsing and multiple lesions [2]. CNO can affect children of all ages, but its peak of incidence occurs between 7 years and 12 years. Although the disease is spread globally, its prevalence is apparently higher in Europe. The female: male ratio ranges from 1.5:1.0 to 4:1, according to the studied population [3,4].

CNO is rare and probably underdiagnosed; true prevalence is estimated at 1:10.000 [5]. Diagnosis is often delayed due to its varied and nonspecific initial symptoms. It is characterized by insidious onset of bone inflammation, with or without swelling, which can lead to chronic bone pain, edema, bone deformities and fractures. Systemic features, including fever and malaise, are usually mild [6].

At the moment, there is no identified gene underlying the molecular pathophysiology of CNO. The disease can happen sporadically or as a manifestation of monogenic autoinflammatory syndromes such as Majeed syndrome, Deficiency of Interleukin 1 Receptor Antagonist (DIRA) and Synovitis, Acne, Pustulosis, Hyperostosis and Osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome; it is still not clear if those are different entities or spectra of the same disease [7].

Treatment is usually based on Nonsteroidal Anti- Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, methotrexate, bisphosphonates and Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), albeit agents like sulfasalazine, colchicine, alfa interferon gamma and intravenous immunoglobulin have also been anecdotally described [8].

Case series are useful to study rare autoinflammatory diseases such as CNO, since diagnosis, treatment and prognosis are not well stablished. The aim of this report was to describe clinical features, subsidiary exams, treatment and outcome of thirteen cases of CNO followed in a tertiary center in Brazil.

Methods

We carried out a single-center retrospective descriptive review of clinical records, including thirteen children and adolescents with CNO followed between 2010 and 2020 in our tertiary service in Brazil.

Medical records were reviewed in order to collect data about clinical presentation, inflammatory markers, radiological and histological findings, treatment and outcome. Data were collected using a standardized form and analyzed in Excel.

The diagnosis of CNO was based on Bristol diagnostic criteria for CRMO (Table 1) including the presence of unifocal or multifocal bone inflammatory lesions on imaging (plain radiograph, computed tomography - CT or Magnetic Resonance Imaging - MRI) associated with characteristic symptoms, high acute phase reactants and exclusion of more prevalent diseases (infectious, traumatic, oncological and other inflammatory disorders) [6].

The presence of typical clinical findings (bone pain +/- localized swelling without significant local or systemic features of inflammation or infection) |

|---|

| AND |

| The presence of typical radiological findings (plain x-ray: showing combination of lytic areas, sclerosis and new bone formation or preferably STIR MRI: showing bone marrowedema +/- bone expansion, lytic areas and periosteal reaction) |

| AND/ EITHER |

| Criterion 1: more than one bone (or clavicle alone) without significantly raised CRP (CRP < 30 g/L). |

| OR |

| Criterion 2: if unifocal disease (other than clavicle), or CRP >30 g/L, with bone biopsy showing inflammatory changes (plasma cells, osteoclasts, fibrosis or sclerosis) with no bacterial growth whilst not on antibiotic therapy |

CRP: C-Reactive Protein; STIR-MRI: Short Inversion Time Inversion Recovery Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Table 1. Bristol diagnostic criteria for chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis [6].

Table 1 Per treatment response, we discriminated three possible scenarios: no response, partial response and clinical remission. No response was defined as absence of improvement of pain and number of inflammatory lesions on MRI; partial response as decrease of pain and/ or number of inflammatory lesions on MRI; or clinical remission as absence of clinical symptoms including pain, redness, swelling, or heat feeling, absence of acute phase reactants and absence of active lesions on MRI [9].

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were described as median and ranges and categorical variables as percentages and frequencies. The study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of Universidade Federal de São Paulo.

Results

Thirteen patients were included in this study, of whom 46% were female. Median of current age and of followup time were 11 y(range 8.5-20.4) and 40 months (range 9-123), respectively. Median age at disease onset was 8.1 y(range 0.8–15.3) and median age at diagnosis was 11 y(range 7-16.1). The most affected sites were metaphysis and diaphysis of long bones. Median number of initially affected bones was 4.0 (range 1-7). Five patients had recurrences.

Malaise and fever were present in 10 (77%) and 6 (46%) patients, respectively. All patients presented with bone pain and/or arthralgia.

All patients had increased acute phase reactants at disease onset: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) was elevated (>20 mm/h) in all thirteen patients (median 68 mm/h, range from 28 to 121), while C Reactive Protein (CRP) was elevated in eleven (85%) (median 31.67 mg/L, range from 6.43 to 200).

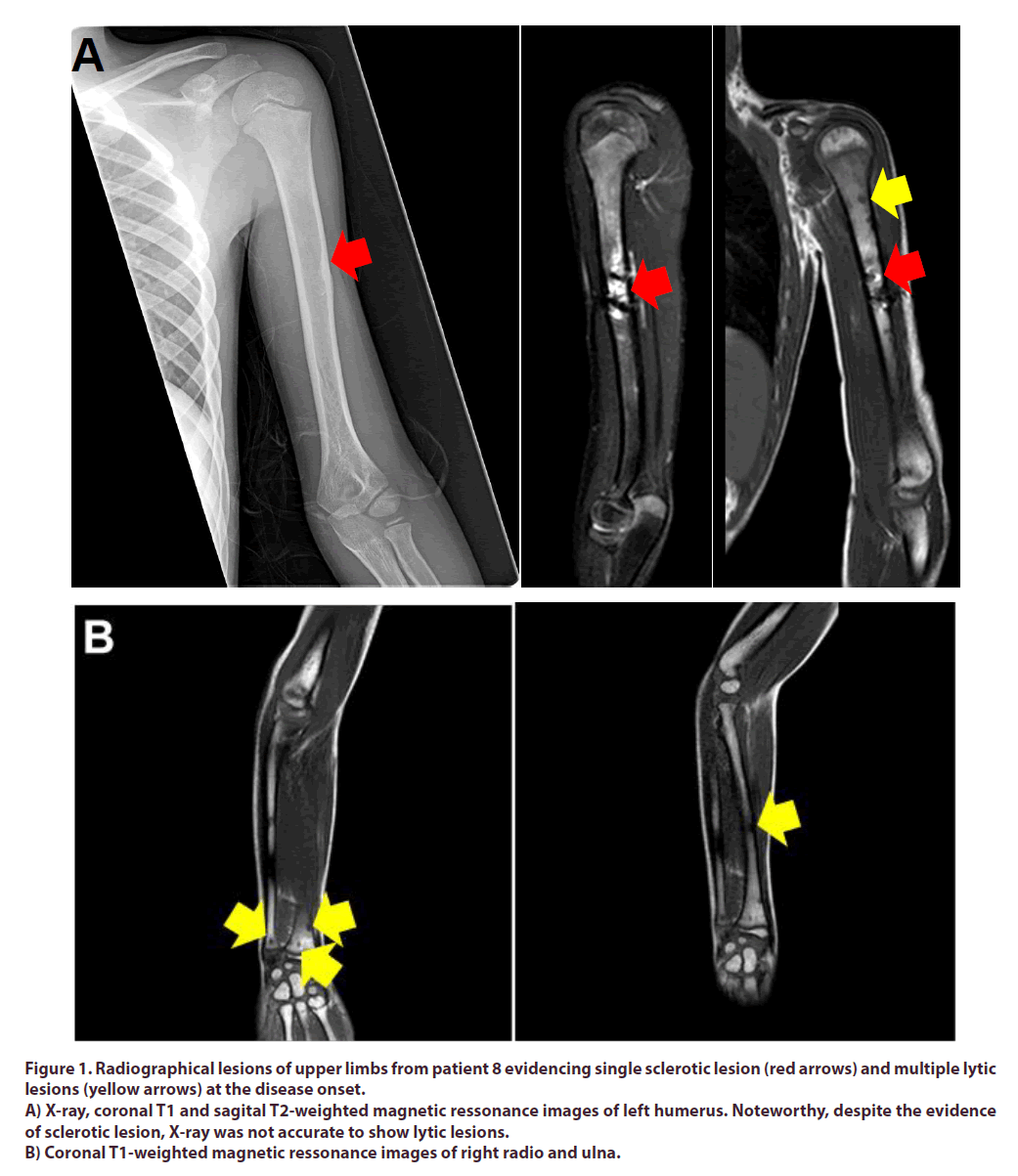

Conventional X-rays were available for diagnosis in all patients and were altered in all at the symptomatic region. The most used additional imaging method was MRI (thirteen patients) for local lesions. All patients had characteristic findings on MRI, such as bone marrow and soft tissue edema, (lytic lesions, osteitis, hyperostosis and periostitis). The most common finding was lytic bone lesions, presented in all patients, followed by periostitis, in six patients (Figure 1). Scintigraphy was performed on just one patient and it was normal. CT was not used for diagnosis or follow-up in any of these cases.

Figure 1. Radiographical lesions of upper limbs from patient 8 evidencing single sclerotic lesion (red arrows) and multiple lytic lesions (yellow arrows) at the disease onset.

A) X-ray, coronal T1 and sagital T2-weighted magnetic ressonance images of left humerus. Noteworthy, despite the evidence of sclerotic lesion, X-ray was not accurate to show lytic lesions.

B) Coronal T1-weighted magnetic ressonance images of right radio and ulna.

Bone biopsies were performed in all patients. Histological investigations showed nonspecific inflammatory changes with granulocytic infiltration and fibrotic and/ or hyperostotic regeneration; culture was negative in all samples analyzed.

All patients received NSAIDs therapy (indomethacin or naproxen); two of them as single therapy with clinical remission. Among our eleven patients whose disease was not controlled with NSAIDs, one achieved remission with methotrexate, five achieved remission with alendronate and methotrexate and one with the surprising association of prednisone and azathioprine, due to unconfirmed suspicion of autoimmune pancreatitis (patient 8); two had partial response to alendronate and one to methotrexate; and one who is presenting with refractory disease to NSAIDs, alendronate, prednisone and methotrexate is currently on anti-TNF agent. In summary, five patients received systemic glucocorticoids, eight received methotrexate and seven received bisphosphonates (alendronate). The demographic, clinical, laboratorial and therapeutic data are described in Tables 1 & 2.

The main affected areas were the long bones of lower limbs. Lesions in tibia were visualized in 10 (77%) patients and in femur, in 7 (54%) patients. The affected bones are showed in Table 3.

Findings |

N=13 |

|---|---|

| Girls, n (%) | 6 (46) |

| Age at disease onset in years, median (min-max) | 8.1 (0.8-15.3) |

| Age at diagnosis in years, median (min-max) | 11 (7-16.1) |

| Time up to diagnosis in years, median (min-max) | 2 (0-8.8) |

| Follow-up time in months, median (min-max) | 40 (9-123) |

| Current age in years, median (min-max) | 11 (8.5-20.4) |

| Fever, n (%) | 6 (46) |

| Malaise, n (%) | 10 (77) |

| Weight loss, n (%) | 2 (15) |

| Bone pain or arthralgia, n (%) | 13 (100) |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 4 (31) |

| Elevated ESR, n (%) | 13 (100) |

| Elevated CRP, n (%) | 11 (85) |

| Bone lytic lesions in X-Ray, n (%) | 13 (100) |

| Changes in MRI, n (%) | 13 (100) |

| Bone biopsy, n (%) | 13 (100) |

| Treatment | |

| NSAIDS, n (%) | 13 (100) |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 5 (38) |

| Metotrexate, n (%) | 8 (62) |

| Bisphosphonates, n (%) | 7 (54) |

| Azathioprine, n (%) | 1 (8) |

| Anti-TNF, n (%) | 1 (8) |

ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; CRP:C-Reactive Protein; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; NSAIDs:Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; Anti –Tnf: Anti- Tumor Necrosis Factor

Table 2. Demographic, clinical, laboratorial and therapeutic data from 13 patients with Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis (CNO).

Bone Affected |

N (%) |

|---|---|

| Tibia, n(%) | 10 (77) |

| Femur, n(%) | 7 (54) |

| Patella, n(%) | 5 (38) |

| Clavicle n (%) | 4 (31) |

| Fibula n (%) | 3 (23) |

| Calcaneus, n (%) | 3 (23) |

| Ankle n(%) | 2 (15) |

| Humerus, n(%) | 2 (15) |

| Radio, n(%) | 2 (15) |

| Ulna, n(%) | 2 (15) |

| Mandible | 1 (8) |

| Ischium, n(%) | 1 (8) |

| Acetabulum, n(%) | 1 (8) |

| Talus, n(%) | 1 (8) |

Table 3. The most affected bones in 13 patients with Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis (CNO).

Table 4 illustrates the demographic, clinical, affected site in imaging, treatment and outcome data of the patients with CNO. One patient had dyserythropoietic anemia, receiving diagnosis of Majeed syndrome (patient 1). Six presented with bone local edema (patients 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 13). One patient had palmoplantar pustulosis, recurrent oral ulcers and monoarthritic of the hip joint (patient 7).

Patients |

Gender | Age of Onset | Clinical features | Affected site | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 9 mo | Fever, malaise, bone pain and arthralgia | Proximal third of right tibia | NSAID, alendronate | Partial response |

| 2 | Female | 14 yo | Fever, malaise, bone pain and arthralgia | Left tibia, fibula, patella, femur, calcaneus and talus | NSAID | Remission |

| 3 | Female | 15 yo | Fever, malaise, arthritis, arthralgia, and myalgia | Right femur proximal metaphysis, left femur distal diaphysis, bilateral femur distal metaepiphysial region, left tibial proximal metaphysis, right tibia metaphysis and proximal diaphysis | NSAID | Remission |

| 4 | Female | 8 yo | Bone pain and local edema | Right mandible | NSAID, prednisone, alendronate, methotrexate | Remission |

| 5 | Female | 11 yo | Bone pain and local edema, arthralgia and arthritis | Left clavicle | NSAID, methotrexate, anti-TNF agent | No response |

| 6 | Male | 11 yo | Malaise, bone pain and local edema and arthralgia | Left clavicle, ankle, calcaneus, tibia metaphysis | NSAID, alendronate | Partial response |

| 7 | Female | 6 yo | Bone pain, arthralgia and monoarthritis | Right fibula metaphysis, left tibia metaphysis, bilateral femur metaphysis, left acetabulum, ischium and ischiopubic ramus | NSAID, prednisone, methotrexate, | Partial response |

| 8 | Male | 8 yo | Fever, malaise, bone pain, lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly | Left humerus proximal metaphysis and diaphysis, right radium and right ulna distal metaphysis and diaphysis, bilateral patella, bilateral distal tibia | NSAID, prednisone, azathioprine | Remission |

| 9 | Male | 12 yo | Malaise, bone pain and local edema | Right radium and left ulna distal metaphysis, left femur proximal metaphysis, left femur distal diaphysis, right tibia proximal metaphysis, | NSAID, prednisone, methotrexate, alendronate | Remission |

| 10 | Male | 9 yo | Fever, malaise, arthralgia and bone pain | Right humerus metaphysis, bilateral femoral metaphysis | NSAID, alendronate, methotrexate | Remission |

| 11 | Male | 10 yo | Malaise, bone pain and local edema | Right clavicle, right ankle, left calcaneus,left tibia metaphysis | NSAID, methotrexate | Remission |

| 12 | Male | 7 yo | Malaise, arthralgia and arthritis | Right femur proximal metaphysis, left tibia proximal metaphysis, bilateral patella | NSAID, alendronate, methotrexate | Remission |

| 13 | Female | 11 yo | Fever, malaise, bone pain and local edema, | Bilateral clavicle, left fibula metaphysis | NSAID, prednisone, methotrexate, alendronate | Remission |

Mo:Months Old; yo:Years Old; NSAID: Non Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug

Table 4. Demographic, clinical, affected site in imaging, treatment and outcome data of the patients with Chronic Noninfectious Osteomyelitis (CNO).

Discussion

The diagnosis of CNO in children is often delayed because of the lack of awareness among physicians and the still unknown nature of CNO. Prompt referral to a pediatric rheumatologist can help to establish an early diagnosis and to start appropriate treatment [6]. The aim of this report was to describe thirteen cases of patients diagnosed with CNO and its particularities.

The median age at symptom onset has been reported to be 9-10 years in other studies[10]; similarly, in the present case series, the median age at symptoms onset was 8.1 years. The median delay in diagnosis was 2 years, which is higher than found by Roderick et al (15 months) in a 41-patient cohort with broader imaging studies availability [6] and in a large registry study including 486 children with CNO from 19 countries, mean age 9.9 years, and the mean time to diagnosis was 1 year [10].

Most of our patients presented with recurrent bone pain and six of them also had local edema, which are the main described manifestations [9-12]. Eight patients had arthralgia, while four of them had arthritis. Although CNO is not considered to be an autoinflammatory syndrome with periodic fever, occasional fever can be present as observed in six of our patients. Malaise was also common.

CNO is a challenging diagnosis. Some of the clues that should raise the suspicion of this pathology are the long and relapsing course, lack of response to antibiotics, negative bone cultures, no abscess, no periodic fever and no significant constitutional symptoms. Because the disease remains a diagnosis of exclusion, many patients receive long term courses of antibiotics and undergo multiple bone biopsies before the diagnosis is suspected [3,5]. There are no specific clinical, laboratory or imaging findings and several diagnostic criteria were proposed to help the investigation process, including the Bristol Diagnostic Criteria (Table 1). In case of unifocal disease, biopsy may be crucial to rule out infectious or neoplastic diseases [6].

The main sites of inflammation in CNO are the metaphysis of long bones (especially tibia and fibula), clavicle and vertebrae. The most common sites of disease have been reported were the femur, tibia and pelvic bones [13,14]. Involvement of the mandible may also occur, and when it is the only site involved it is called Cherubism as in patient 4 [11]. Diaphysis of long bones may also be involved as seen in a small part of our patients3,5.

Andronikouet al., described two main patterns of bone involvement in CNO, the "tibio-appendicular mutifocal" and the "claviculo-spinal paucifocal" patterns, with prevalence of 54% and 24% respectively in that case series [13]. The former was defined by tibial but not clavicular involvement, whereas the latter by clavicular but not tibial involvement, with few additional lesions, mainly of the spine. In our series we found 7 (53,8%) patients with the tibio-appendicular multifocal pattern, and 2 (15,3%) with the claviculo-spinal paucifocal pattern [13].

Multiple disorders have been associated with CNO, such as palmoplantar pustulosis, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, peripheral arthritis, sacroiliitis and dyserythropoietic anemia [1,2] One of our patients presented with palmoplantar pustulosis and recurrent oral ulcers (patient 7) and one with dyserythropoietic anemia(Majeed syndrome). In a series of 19 Chilean children with CNO, all patients presented with multifocal lesions, but no association was observed with psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, or palmoplantar pustulosis [15]. In Irish national cohort showed a high prevalence of extraosseous (40.9%) and cutaneous (27.2%) involvement associated with CNO [16].

Disease activity is seen in radiography or CT as lytic lesions with or without bone sclerosis in metaphysis; and in MRI as bone marrow edema with heterogeneous enhancement after contrast injection. Bone sclerosis occurs in the subacute phase as part of the healing process. With disease remission, the radiographic changes may disappear over time [17]. MRI is more sensitive in detecting disease activity and has the additional value of showing asymptomatic lesions, therefore it was performed in all our patients [18-22]. Increased inflammatory markers seem to predict the number of MRI sites involved, suggesting that the number of MRI sites represents a marker for disease activity [14].

Imaging studies are fundamental for diagnosis and follow-up of CNO patients. MRI stands out as the best method for diagnosis and monitoring [22-25]. Due to the relapsing nature of this disease, long term followup is advised. Patients should be monitored for disease activity and for complications such as limb asymmetry and compression fractures of the vertebrae [8].

The first line treatment is NSAIDs and it is an effective therapy for most patients [24]. Two of the thirteen patients in this cohort responded well to NSAIDs. Bisphosphonates, prednisone, methotrexate and anti- TNF agents can be used as a second line therapy in refractory cases, with good outcomes [8,10,17-19,23]. Among our eleven patients whose disease was not controlled with NSAIDs, 7 achieved remission and 2 partial response using second line drugs; and one who is presenting with refractory disease to NSAIDs, alendronate, prednisone and methotrexate is currently on anti-TNF agent. Three consensus treatment plans for the first 6–12 months were developed by members of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) for pediatric patients with CNO refractory to NSAIDs: (1) methotrexate or sulfasalazine, (2) tumor necrosis factor (TNF)alpha inhibitors with optional use of methotrexate, and (3) bisphosphonates [26].

Awareness of the features of CNO is important for an early diagnosis and may avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures and prolonged antibiotic therapies.

References

- Costa–Reis P, Sullivan KE. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. J. Clin. Immunol. 33(6), 1043–1056 (2013).

- Roderick MR, Sen ES, Ramanan AV et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children and adults: current understanding and areas for development. Rheumatology (Oxford).57(1),41–48 (2018).

- Wipff J, Costantino F, Lemelle I et al. A large national cohort of French patients with chronic recurrent multifocal osteitis. Arthritis. Rheumatol. 67(4), 1128–1137 (2015).

- Jansson AF, Grote V. Nonbacterial osteitis in children: data of a German Incidence Surveillance Study. Acta. Paediatr. 100(8), 1150–1157 (2011).

- Walsh P, Manners PJ, Vercoe J et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children: nine years' experience at a statewide tertiary paediatric rheumatology referral centre. Rheumatology (Oxford). 54(9), 1688–1691 (2015).

- Roderick MR, Shah R, Rogers V et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) – advancing the diagnosis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online. J. 14(1), 47 (2016).

- Hedrich CM, Hofmann SR, Pablik J et al. Autoinflammatory bone disorders with special focus on chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online. J. 11(1), 47 (2013).

- Schnabel A, Range U, Hahn G et al. Treatment response and longterm outcomes in children with chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. J. Rheumatol. 44(7), 1058–1065 (2017).

- Ata Y, Inaba Y, Choe H et al. Bone metabolism and inflammatory characteristics in 14 cases of chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Pediatr.Rheumatol. Online J. 15(1), 56 (2017).

- Girschick H, Finetti M, Orlando F et al., Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) and the Eurofever registry. The multifaceted presentation of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: a series of 486 cases from the Eurofever international registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 57(7), 1203–1211 (2018).

- Padwa BL, Dentino K, Robson CD et al. Pediatric chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis of the jaw: clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic features. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 74(12), 2393–2402 (2016).

- Jansson A, Renner ED, Ramser J et al. Classification of non–bacterial osteitis: retrospective study of clinical, immunological and genetic aspects in 89 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 46(1), 154–160 (2007).

- Andronikou S, Mendes da Costa T, Hussien M et al. Radiological diagnosis of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis using whole–body MRI–based lesion distribution patterns. Clin.Radiol. 74, 737.e3–737.e15 (2019).

- d'Angelo P, de Horatio LT, Toma P et al. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis – clinical and magnetic resonance imaging features. Pediatr. Radiol. 51(2), 282–288 (2021).

- Concha S, Hernández–Ojeda A, Contreras O et al. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis in children: a multicenter case series. Rheumatol. Int. 40(1):115–120.

- O'Leary D, Wilson AG, MacDermott EJ et al. Variability in phenotype and response to treatment in chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis; the Irish experience of a national cohort. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online. J. 19(1), 45 (2021).

- Fritz J, Tzaribatchev N, Claussen CD et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: comparison of whole–body MR imaging with radiography and correlation with clinical and laboratory data. Radiology. 252(3), 842–851(2009).

- Earwaker JWS, Cotton A. SAPHO: syndrome or concept? Imaging findings, Skeletal Radiol. 32, 311–327 (2003).

- Chen MFW, Chang JH, Nieves–Robbins NM et al. The role of whole–body magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosing chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Radiol. Case. Rep. 13, 485–489 (2018).

- Nguyen MT, Borchers A, Selmi C et al. The SAPHO Syndrome. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 42, 254–265 (2012).

- Jurik AG, Klicman RF, Simoni P et al. SAPHO and CRMO: the value of imaging. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 22, 207–224 (2018).

- Zhao Y, Laxer R, Ferguson P et al. Treatment advances in chronic non–bacterial osteomyelitis and other autoinflammatory bone conditions. Curr. Treatm. Opt. Rheumatol. 3, 17 (2017).

- Zhao Y, Chauvin NA, Jaramillo D et al. Aggressive therapy reduces disease activity without skeletal damage progression in chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. J. Rheumatol. 42(7), 1245–1251 (2015).

- Beck C, Morbach H, Beer M et al. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis in childhood: prospective follow–up during the first year of anti–inflammatory treatment. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 12(2), R74 (2010).

- Zhao Y, Ferguson PJ. Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis and Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis in Children. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 65, 783–800 (2018).

- Zhao Y, Wu EY, Oliver MS et al. Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis/Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis Study Group and the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Scleroderma, Vasculitis, Autoinflammatory and Rare Diseases Subcommittee. Consensus Treatment Plans for Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis Refractory to Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and/or With Active Spinal Lesions. Arthritis. Care. Res. (Hoboken).70(8), 1228–1237 (2018).