Short Article - Interventional Cardiology (2010) Volume 2, Issue 2

Concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitor: a reality check

- Corresponding Author:

- Subhash Banerjee

University of Texas

Southwestern Medical Center

4500 S Lancaster Road (111a), Dallas, TX 75216, USA

Tel: +1 214 857 1608

Fax: +1 214 857 1474

E-mail: subhash.banerjee@va.gov

Abstract

Keywords

cardiovascular outcome, clopidogrel, proton-pump inhibitor

Consensus guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association endorse the use of proton-pump inhibitor(s) (PPI) in patients judged to be at higher risk for gastrointestinal (GI) ulceration and related complications [1]. This recommendation is largely based on an observational study reporting PPI cotherapy to be beneficial in reducing the risk of upper GI bleed in patients on clopidogrel monotherapy [2]. This effect is possibly due to inhibition of the gastric parietal cell proton pump and suppression of gastric acid production by PPI, especially in aspirin-treated patients [3–5]. This recommendation has in turn fuelled widespread empiric use of PPIs, especially omeprazole in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and clopidogrel [5,6].

Mechanism

Recent studies have reported significant reduction in the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel in patients on omeprazole [7]. Ex vivo studies have demonstrated an attenuated antiplatelet effect, measured by ADP-induced platelet aggregation and elevated residual platelet activity [8,9]. These studies are supported by some large retrospective analyses demonstrating excess cardiovascular events in patients taking clopidogrel with any PPI versus clopidogrel alone [10–13]. The mechanism of this adverse interaction is possibly due to competitive interference of the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP450) pathway by PPIs. PPIs are metabolized using the same pathway responsible for biotransformation of clopidogrel, a prodrug, into its biologically active metabolite. This may in turn lead to reduced amounts of active clopidogrel metabolite and a resultant reduction in platelet inhibition [14–15].

Current evidence

The Omeprazole Clopidogrel Aspirin (OCLA) study randomized 140 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on clopidogrel to omeprazole 20 mg daily or placebo [16]. The primary end point was platelet reactivity index (PRI) after 7 days of concomitant exposure. A higher PRI designates lower clopidogrel response on platelet aggregation. The mean ± standard deviation PRI was measured by platelet phosphorylated vasodilatorstimulated phosphoprotein (VASP). At 7 days, PRI for the placebo group was 39.8 ± 15.4% and 51.4 ± 16.4% in the omeprazole-treated group (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in baseline PRI. Siller-Matula et al. then reported PRI in 300 PCI patients on clopidogrel maintenance therapy, exposed to pantoprazole and esomeprazole [8]. The mean PRI in the clopidogrel and PPI group was 51% (95% CI: 48–54%) and for the clopidogrel-only group the mean PRI was 49% (95% CI: 43–55%), indicating that pantoprazole and esomeprazole may not be competitive inhibitors of clopidogrel, unlike omeprazole. No baseline PRI was reported, and the PRI values for pantoprazole and esomeprazole were similar to that reported in the OCLA trial for omeprazole. Another study attempting to compare clopidogrel response on platelet aggregation by impedance aggregometry in 1000 PCI patients treated with omeprazole (n = 64), esomeprazole (n = 42) or pantoprazole (n = 162), was limited by having only a small number of patients on these individual PPIs [9]. Even though patients on omeprazole had a reduced response to clopidogrel compared with other PPIs (32.8 vs 19.1%; p = 0.008), prior myocardial infarction, diabetes, BMI and smoking were also predictors of increased aggregation.

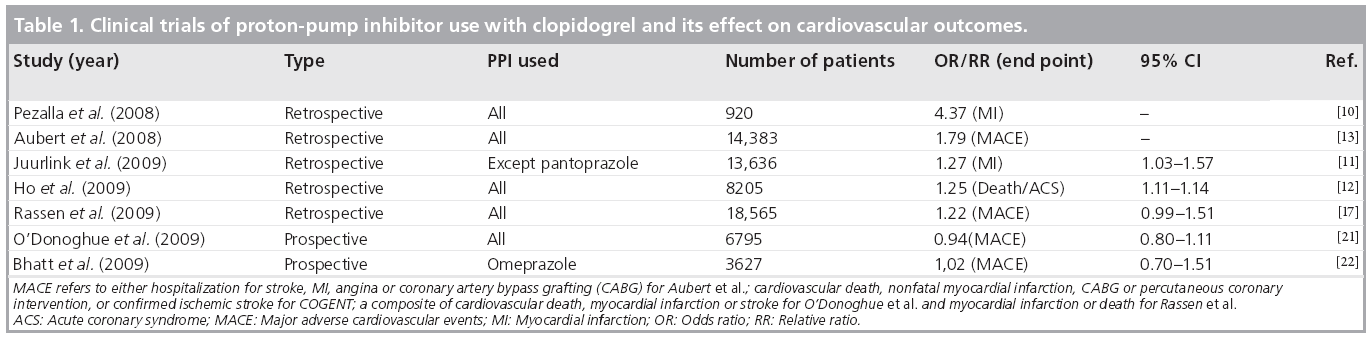

A retrospective cohort study by Pezalla et al. reported 3.08 and 5.03% 1‑year myocardial infarction (MI) rates for low and high PPI exposure compared with 1.38% in non-PPI exposed patients in the control group (Table 1) [10]. Juurlink et al., in a case–control study from Canada, examined death and readmission for MI of 734 patients with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) discharged on clopidogrel with or without a PPI [11]. PPI use was associated with an increased odds of MI compared with the no-PPI group (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.03–1.57). The study, for the first time, also examined the risk associated with specific PPIs and concluded that pantoprazole was not associated with this elevated risk of MI when used concomitantly with clopidogrel. Both studies by Pezalla and Juurlink were associated with significant differences in the comorbid conditions between the study groups. Moreover, the pantoprazole analysis by Juurlink was based upon 46 patients treated with the drug in the study cohort. Ho et al. have, thus far, performed the most comprehensive analysis from a Veterans Affairs database of ACS patients treated conservatively with medical therapy only, or with revascularization in addition to medical therapy [12]. In this large study sample of 5244 patients exposed to clopidogrel and a PPI, the OR of death and readmission for ACS was 1.25 (95% CI: 1.11–1.41) compared with those treated only with clopidogrel (n = 2961). Over 59% of patients in the study received omeprazole and its use was associated with an increased risk of death and readmission for ACS (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.08–1.41). Importantly, this increased risk for cardiovascular events was not evident in nonclopidogrel-treated patients. A more recent analysis by Rassen et al. used a sophisticated multivariate analysis to report an OR of 1.22; 95% CI: 0.99–1.51, for death or MI associated with PPI use [17]. Researchers from the Medco study used data from 16,690 patients taking clopidogrel after stenting and found that the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; hospitalization for stroke, MI, angina or coronary bypass surgery) was raised from 17.9 to 25.1% in patients also taking PPIs [13]. This study has only been presented as an abstract in the annual scientific session of the Society of Coronary Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). Another study by Dunn et al., also published only as an abstract, has reported an increased risk of cardiovascular events in PPI-treated patients from the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial [18]. However, this substudy also demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the therapeutic effect of clopidogrel in PPI-treated patients compared with non-PPI-treated patients. Our own data of clopidogrel and PPI use, recently presented at the European Society of Cardiology national meeting in 2009, showed an increased risk of death and MI in a small cohort of patients treated exclusively with drug-eluting coronary stents [19]. A similar, yet unpublished outcome analysis of 32,946 post- PCI patients from the Veterans Affairs National Pharmacy Management Database has shown no evidence of an adverse association with concomitant exposure to clopidogrel and PPIs [20]. Most of these high-profile studies have been retrospective and based upon discharge medications and prescription data obtained at any time during the follow-up period without an assessment of drug exposure at the time of MACE and without adequate adjustments for confounding variables. Furthermore, the studies do not account for interruption in clopidogrel or PPI use during the follow-up period and nor do they present exposure analysis at the end point. They do not account for additional factors that may contribute to variability in clopidogrel response, such as compliance with therapy, variable intestinal absorption, differences in platelet response to ADP, and genetic differences in CYP metabolic activity [15].

Table 1: Clinical trials of proton-pump inhibitor use with clopidogrel and its effect on cardiovascular outcomes.

Nevertheless, on the basis of these early reports, over-the-counter availability of PPIs, their widespread use in patients on DAPT and the potential for harm, many national and international organizations and regulatory bodies rushed to issue position statements, warnings or guidelines on the use of PPIs and clopidogrel. The US FDA has also recently issued a warning stating, “new data show that when clopidogrel and omeprazole are taken together, the effectiveness of clopidogrel is reduced. Patients at risk for heart attacks or strokes who use clopidogrel to prevent blood clots will not get the full effect of this medicine if they are also taking omeprazole” [101]. It would not be an exaggeration to state that these recommendations have been received with great skepticism and confusion by providers and patients alike, and have ignited significant debate.

Much of the confusion arises from the fact that the above position statements disregard data from post hoc analysis of large randomized controlled trials that report no adverse outcome in patients exposed to clopidogrel and PPI. Data from the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel - Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON-TIMI) 38 trial do not demonstrate an increased risk for MI, stroke or death in patients treated with a thienopyridine and PPI, despite inadequate inhibition of platelet aggregation observed in Prasugrel In Comparison to Clopidogrel for Inhibition of Platelet Activation and Aggregation (PRINCIPLE)-TIMI 44 study with PPI exposure [21]. In addition, the reduction in platelet inhibition in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial is thought to be due to the presence of prevalent reduction-in-function polymorphisms of the specific CYP450 gene (CYP2C19) that may result in decreased efficiency of clopidogrel biotransformation to its active metabolite. In the Clopidogrel and the Optimization of Gastrointestinal Events (COGENT) trial, 3627 patients with an ACS and/or PCI were randomized to clopidogrel alone or a combined pill containing a delayed-release omeprazole core with surrounding clopidogrel 75 mg [22]. The study was terminated early for financial reasons; however, there was no increased risk of cardiovascular events observed in the clopidogrel and PPI group. Again, these studies are post hoc analyses of randomized trials. It can also be argued that the results from the COGENT trial merely reflect the temporal separation of pharmacodynamic effects of both the drugs released at different time points. Most PPIs have a short half-life (30 min–2 h) and separating them over time may minimize the chance of adverse interactions.

Recommendations

In terms of practical recommendations for prescribing clopidogrel and PPIs, it would be fair to say that the effect is, at best, modest; however, not trivial since it relates to death and MI. This issue has gained much traction as it does have a pharmacodynamic basis. In addition, the fact that PPIs are available over-the-counter, makes the true estimate of its effect on cardiovascular outcomes hard to assess in real time, along with increasing the potential for widespread uncontrolled use by patients, which make this an issue of great importance to resolve. Therefore, the evidence for the FDA position on the concomitant use of clopidogrel and PPI can be challenged, yet it is understandable from a public health policy perspective. Our primary recommendations for practitioners at this given time are first to avoid empiric use of PPIs with clopidogrel. Second, it might be logical to prefer pantoprazole to other PPIs. Although the FDA recommendation states that separating the dose of clopidogrel and omeprazole in time, will not reduce this drug interaction, we still advocate temporally separating the two drugs by advising patients to take them at least 4–6 h apart. This takes into consideration the mechanism of interaction (competitive interference in metabolism of clopidogrel) and the pharmacokinetics of both drugs as most PPIs have a short half-life (30 min–2 h). We believe that these common sense measures might minimize the risk of potential adverse interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs, until more conclusive evidence on this ongoing question are presented.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Executive summary

▪ There is widespread empiric prescription of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) to patients on clopidogrel and aspirin therapy.

▪ Adverse interactions are observed between PPIs and clopidogrel.

- PPIs competitively inhibit the conversion of the clopidogrel, a prodrug to its biologically active metabolite.

▪ There are clinical evidence for the adverse effect of PPI coadministration with clopidogrel.

- Retrospective analyses are limited, confounded and not supported by data from post hoc analysis of prospective trials.

- Data from large randomized controlled trials report no adverse outcome in patients exposed to clopidogrel and PPIs (the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel – Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TRITON-TIMI] 38 and the Prasugrel In Comparison to Clopidogrel for Inhibition of Platelet Activation and Aggregation [PRINCIPLE]-TIMI 44 studies).

▪ As PPIs are available over-the-counter, US FDA warnings on concomitant use of PPIs and clopidogrel are justified, but may be overstated.

References

- Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS et al.: ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 118, 1894–1909 (2008).

- Lanas A, Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Arroyo MT et al.: Effect of antisecretory drugs and nitrates on the risk of ulcer bleeding associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102, 507–515 (2007).

- Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM et al.: Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 2033–2038 (2002).

- Chan FK, Chung SC, Suen BY et al.: Preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low-dose aspirin or naproxen. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 967–973 (2001).

- Lanas A, Rodrigo L, Marquez JL et al.: Low frequency of upper gastrointestinal complications in a cohort of high-risk patients taking low-dose aspirin or NSAIDS and omeprazole. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 38, 693–700 (2003).

- Tan VP, Yan BP, Kiernan TJ et al.: Risk and management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 10, 36–44 (2009).

- Gilard M, Arnaud B, Le Gal G et al.: Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated to aspirin. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 2508–2509 (2006) (Letter).

- Siller-Matula JM, Spiel AO, Lang IM et al.: Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. Am. Heart J. 157, 148, E1–E5 (2009).

- Sibbing D, Morath T, Stegherr J et al.: Impact of proton pump inhibitors on the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel. Thromb. Haemost. 101, 714–719 (2009).

- Pezalla E, Day D, Pulliadath I: Initial assessment of clinical impact of a drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1037–1039 (2008) (Letter).

- Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT et al.: A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ 180, 713–718 (2009).

- Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L et al.: Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 301, 937–944 (2009).

- Aubert RE, Epstein RS, Teagarden JR et al.: Proton pump inhibitors effect on clopidogrel effectiveness: the Clopidogrel Medco Outcomes Study. Circulation. 118, S815 (2008) (Abstract 3998).

- Li XQ, Andersson TB, Ahlström M et al.: Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metab. Dispos. 32, 821–827 (2004).

- Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD et al.: Cytochrome P-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N. Engl. J. Med 360, 354–362 (2009).

- Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC et al.: Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole Clopidogrel Aspirin) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51, 256–260 (2008).

- Rassen JA, Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Schneeweiss S: Cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients using clopidogrel with proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention or acute coronary syndrome. Circulation 120, 2322–2329 (2009).

- Dunn SP, Macaulay TE, Brennan DM et al.: Baseline proton pump inhibitor use is associated with increased cardiovascular events with and without the use of clopidogrel in the CREDO trial. Circulation 118, S815 (2008) (Abstract).

- Banerjee S, Varghese C, Weideman RA et al.: Proton pump inhibitors increase the risk of cardiovascular events in post PCI patients who are on clopidogrel. Presented at: European Society of Cardiology. Barcelona, Spain 29 August–2 September 2009. (Abstract).

- Banerjee S, Weideman RA, Weidman MW et al.: Cardiovascular outcomes with concomitant exposure to clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors in patients with coronary stents implants. Presented at: Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) 2010. 21–23 February, 2010, Washington, DC, USA (Abstract).

- O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM et al.: Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomized trials. Lancet 374, 989–997 (2009).

- Bhatt DL: COGENT: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in patients receiving aspirin and clopidogrel. Presented at: Program and abstracts of the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics, 2009. 24 September 2009, San Francisco, CA, USA.

- US FDA: Information for Healthcare Professionals – Update to the labeling of clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix®) to alert healthcare professionals about a drug interaction with omeprazole (marketed as Prilosec® and PrilosecOTC®) www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/drugSafety InformationforPatientsandProviders/ ucm190787.htm

▪ Website