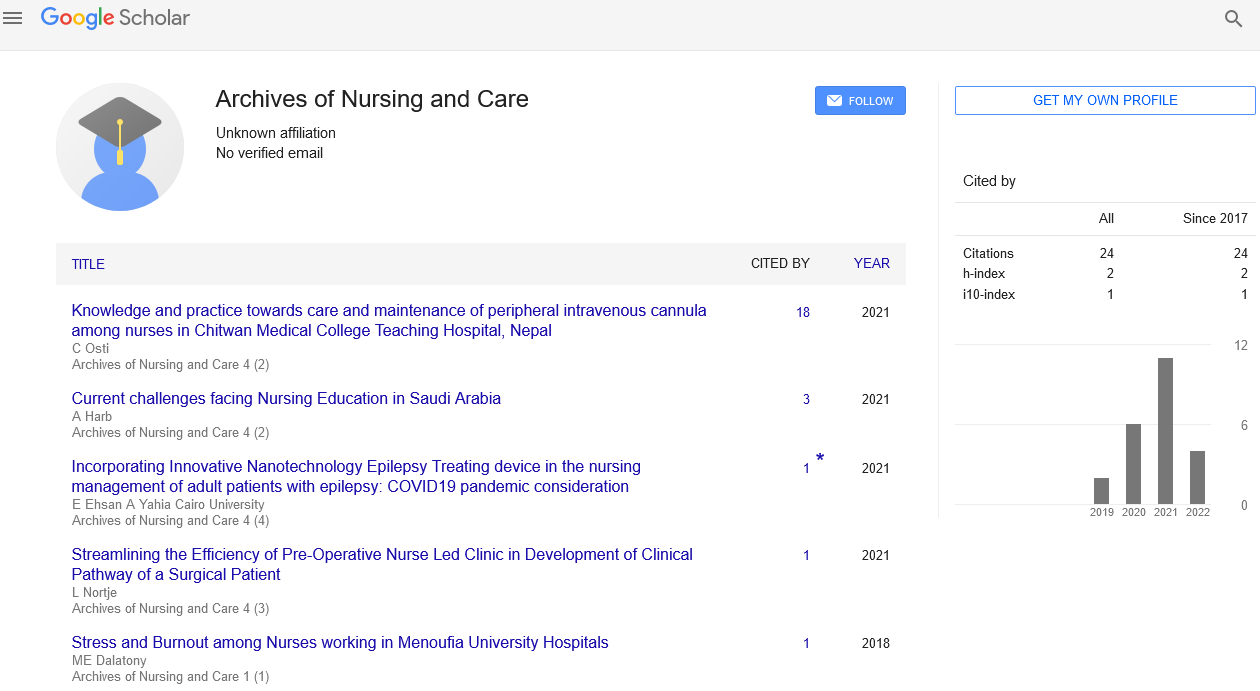

Review Article - Archives of Nursing and Care (2023) Volume 6, Issue 2

Mental health nursing practise: Safety in psychiatric inpatient care

Jennifer Ferguson*

New York Presbyterian Hospital, USA

New York Presbyterian Hospital, USA

E-mail: fergusonjennifer@rediff.com

Received: 03-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. OANC-23-89193; Editor assigned: 05-Apr-2023, PreQC No. OANC-23- 89193 (PQ); Reviewed: 19-Apr-2023, QC No. OANC-23-89193; Revised: 24-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. OANC-23- 89193 (R); Published: 28-Apr-2023, DOI: 10.37532/oanc.2023.6(2). 28-31

Abstract

The treatment of people with mental illness through institutionalisation and into contemporary psychiatric nursing practises has been influenced by the discourse on safety. Confinement developed out of concerns for public safety, societal stigma, and benevolently paternalistic efforts to keep people from harming themselves. In this essay, we contend that risk management serves as the cornerstone of nursing care in current mental inpatient contexts, where safety is maintained as the primary value. Despite evidence disputing their efficacy and patient opinions revealing harm, practises that uphold this ideal are justified and maintained through the safety discourse. We offer four examples of risk management techniques used in psychiatric inpatient settings—close observations, isolation, door locking, and defensive nursing practice—to show this developing issue in mental health nursing care. The implementation of these techniques illustrates the need to change nursing care's viewpoints on safety and risk. We propose that nurses should provide tailored, flexible care that takes safety precautions into consideration in order to provide meaningful assistance and treatment of clients. They should also fundamentally re-evaluate the risk management culture that fosters and justifies harmful activities.

Keywords

mental health • nursing practice • patient safety • risk management

Introduction

A nurse with a focus on mental health who is appointed to care for patients of all ages who are suffering from mental diseases or distress is known as a psychiatric nurse or mental health nurse. These include eating disorders, suicidal ideation, psychosis, paranoia, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disease, mood disorders, addiction, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and self-harm. The administration of psychiatric medications, creating a therapeutic alliance, managing problematic behaviour, and psychological therapies are all areas in which nurses in this field are specifically trained. An extensive range of nursing, psychological, and neurobiological skills are needed for psychiatric-mental health nursing. In addition to assessing, diagnosing, treating, and caring for patients with mental health and drug use issues, PMH nurses also work to prevent illness and educate patients about their rights [1-6].

The second-largest group of behavioural health professionals in the United States is made up of registered nurses (RNs) who specialise in psychiatric-mental health (PMH) and advanced practise registered nurses (APRNs). They work in a range of environments and offer complete care to people on an individual, family, group, and community level. In order to positively impact lives, PMH nurses develop close therapeutic relationships with people of all ages, getting to know their struggles and stories.

Discussion

Mental Illness and Mental Health

Clearly defining mental well-being and mental illness can be challenging. Any civilization's culture has a significant impact on its ideas and values, which in turn have an impact on how that society defines health and illness. One of several post-qualifying curricula that some Member States requested that WHO Europe provide in order to help them move closer to implementing the WHO European Region Continuing Education Strategy for Nurses and Midwives is the Mental Health Nursing programme (WHO 2003). In its original form, the curriculum underwent a protracted consultation process. This version includes all of the specialist modules from the original document in addition to the core modules found in all post-qualifying specialist curricula created by the WHO to complement the previously mentioned Strategy for Continuing Education for Nurses and Midwives. The context for the Continuing Education Strategy is so described at the outset of the Mental Health Nursing curriculum document.

Patients are held accountable for negative outcomes when risk is centred in the person, a process that is interpreted via stigmatising ideas around mental illness. Warner (2010) contends that the internalised stigma that people with mental illness face directly contributes to self-blame and, as a result, to a need for other people's help and support. The recovery models of mental health care aims to untangle the notions of risk and blame by having clients accept ownership of their wellness-promoting behaviours but refrain from placing blame for their symptoms or sickness. Under this concept, nurses assist patients in accepting responsibilities for their own care without reneging on their own professional obligation to provide protection. Recovery-oriented mental health care efforts and research on the effectiveness of the model have mostly targeted community nursing settings because of the program's emphasis on community reintegration and the development of purpose in life. Nevertheless, nurses may use recovery-oriented strategies to help patients as they take on more responsibility for managing their own medications and symptoms, as well as to empower patients via peer support and instruction. By empowering individuals, these measures promote personal responsibility while avoiding placing blame for any possible risk brought on by mental illness symptoms [7-10].

The practise of mental health nursing, commonly referred to as psychiatric nursing, is a specialist area of nursing that deals with providing care to people who have mental health disorders in order to aid in their recovery and enhance their quality of life. Mental health nurses can offer specialised care because of their superior knowledge of the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of mental diseases. In a medical team, they often collaborate with other health care providers in order to give the patient the best possible clinical results.

Safety Practices and Implementation Strategies

It is frequently required to get inpatient psychiatric care to deliver treatments and drugs that cannot be provided on an outpatient basis. Admission to an inpatient facility, however, may sometimes be required for other factors, such as the necessity to safeguard a patient from risky behaviours. The distinct design of the mental ward is crucial to patient safety. The patient may not hurt himself or others if the hazardous items in the mental unit are replaced with non-hazardous ones. Avoiding ligature anchors and ligature materials while building or remodelling a mental health facility may assist to avert many negative outcomes. Ligature anchor points are projections that can hold a patient's weight if they hang themselves. Hooks, knobs, doors, and curtain rods, clothes rods in closets, towel rods, and sprinkler heads are the most typical ligature sites. Since that patient can selfharm in a unit's bathroom, closet, bedroom, and a concealed space, the institution should undergo routine inspections. When doors are not necessary, they should be eliminated. According to reports, the frequency of suicides that followed evading from a closed door was equal to that of open wards. To prevent patients from tying the rope to the hinge, door hinges should be in a continuous piano style from the top to the bottom of the door. Without doors and shelves in place of hooks and rods, wardrobe cabinets should be used. The management of the organisation has a significant impact on patient safety. The amount of time hospital administrators and the board of directors devote to touring and inspecting inpatient facilities has a beneficial impact on safety performance. Three factors make up leadership: availability, experience, and knowledge of the patient safety strategy. The purpose of leadership is to promote worker safety behaviour by fostering learning, cooperation, feedback, and development. They help to create a positive working atmosphere by supporting the workers. They also serve as a support system for the personnel in the event of any unfavourable events. Particularly in inpatient psychiatric hospitals, nurses are crucial to patient safety. In a research, the phrases "close watching" and "vigilant care" were used to characterise the roles of nurses. The head nurse has a significant influence on the nursing staff's culture of patient safety. The chief nurse should effectively communicate, participate in leadership, preserve a healthy culture, and provide patients the attention they need. The high standard of patient care and improved results are closely correlated with the presence of nurses with exp ertise working with mental patients. The personnel should be able to assist patients with self-care and have knowledge of the conditions being treated in the unit. They should be able to offer comfort and impart knowledge about the condition, the available treatments, and how to administer them. They should also be able to recognise and respond to needs associated to trauma. Patient safety also includes staff load as an issue. Each nurse and staff member is given a specific number of patients to take care of, and this number varies based on the patient's health, the staff's expertise and qualifications, and other criteria. When deciding how many people to put on a shift, the quality of care that is delivered is significantly impacted by nurses who lack expertise caring for patients with mental disorders. Also, it is preferable to allocate patients who have been stabilised better to the nurses with less expertise. Taking care of mental patients requires attention to the safety, health, and wellbeing of the staff. The management of the hospital should ensure that the personnel do not experience stress, exhaustion, or work-related distractions. To be able to assist patients suffering from an acute mental illness, staff personnel should be in a good mental condition. To comprehend the patient's situation and reduce mistakes, staff employees need to have effective verbal and writing communication skills. Unfavourable incidents have been linked to communication breakdown in the past. The transfer of a patient also requires appropriate communication since a mistake in conveying the patient's medical and mental history might have catastrophic consequences. When a patient feels threatened, communication enables them to seek protection and assistance.

Conclusion

The safety discourse frames the nature of care delivery for nurses working in mental health inpatient care settings, guiding identification of risks posed by the patients under their care and the treatments used to manage these risks. The primary goal of inpatient psychiatric care is safety, yet this ostensibly good objective is actually entrenched in stigma, fear, and a history of institutionalisation. The articulation and operationalization of the safety value justifies the continued use of nursing techniques that are ineffective and harmful to both patients and nurses in inpatient settings. While safety is an essential part of inpatient psychiatric nursing care, there needs to be a change in how it is perceived and used in order to foster environments that foster meaningful therapeutic engagement and treatment. Inpatient psychiatric treatment has a number of specific adverse occurrences and medical mistakes. Errors and unfavourable occurrences can be reduced with the help of a number of safety measures. Consideration of the structural standards that a psychiatric unit must meet in order to assure the best patient safety is one of the most crucial tactics for enhancing safety in mental health institutions. Moreover, administrators, physicians, nurses, and personnel take proactive measures to guarantee safety. Patients should participate in procedures that can enhance their safety whenever it is practical. The safety discourse outlines the nature of care delivery for nurses working in mental health inpatient care settings, guiding identification of risks posed by the patients under their care and the treatments used to manage these risks. The primary goal of inpatient psychiatric care is safety, yet this ostensibly good objective is really entrenched in stigma, fear, and a history of institutionalisation. The articulation and operationalization of the safety value justifies the continued use of nursing techniques that are ineffective and detrimental to both patients and nurses in inpatient settings. While safety is an essential part of inpatient psychiatric nursing care, there has to be a change in how it is viewed and used in order to foster conditions that foster meaningful therapeutic engagement and treatment.

References

- Happell B, Gaskin CJ. The attitudes of undergraduate nursing students towards mental health nursing: A systematic review. Journal of clinical nursing. 22, 148-158 (2013).

- Edwards D, Burnard P, Coyle D et al. Stress and burnout in community mental health nursing: a review of the literature. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing. 7, 7-14 (2000).

- Ward L. Mental health nursing and stress: Maintaining balance. International journal of mental health nursing. 20, 77-85 (2011).

- Brown AM. Simulation in undergraduate mental health nursing education: A literature review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. 11, 445-449 (2015).

- Barker P, BuchananâBarker P. Myth of mental health nursing and the challenge of recovery. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 20, 337-344 (2011).

- Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. The Lancet. 371, 852-864 (2008).

- WilliamsâReade J, Lamson AL, Knight SM et al. Paediatric palliative care: a review of needs, obstacles and the future. Journal of Nursing Management. 23, 4-14 (2015).

- Hill K, Coyne I. Palliative care nursing for children in the UK and Ireland. British journal of nursing. 21, 276-281 (2012).

- Couch E, Mead JM, Walsh MM. Oral health perceptions of paediatric palliative care nursing staff. International journal of palliative nursing. 19, 9-15 (2013).

- Harrop E, Edwards C. How and when to refer a child for specialist paediatric palliative care. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Education and Practice. 98, 202-208 (2013).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref