Case Report - Neuropsychiatry (2020) Volume 10, Issue 3

Olfactory Meningioma in a 60-Year-Old Woman Presenting Depressive Symptoms and Atypical Visual Hallucinations

- Corresponding Author:

- Simone Marchini

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Erasme Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Brussels, Belgium

Abstract

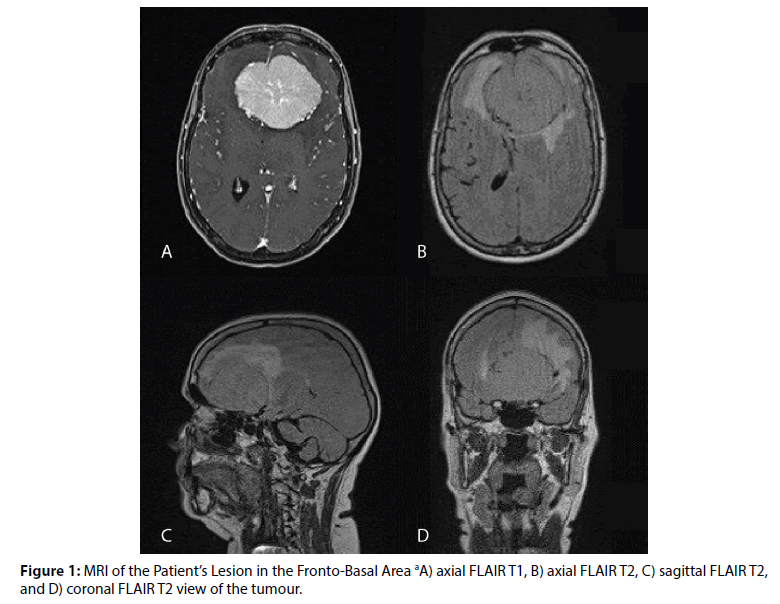

The authors describe a 60-year-old woman with depressive symptoms and visual hallucinations. The patient reported atypical visual hallucinations and typical severe depressive episode. Cerebral MRI showed a fronto-basal lesion measuring 67 mm x 62 mm x 51 mm with mass effect and perilesional oedema highly suspected olfactory meningioma. The atypical visual hallucinations and depressive symptoms were completely resolved after neurosurgery intervention on the fronto-basal olfactory meningioma. The Perception and Attention Deficit (PAD) model allows understanding of the double role of the olfactory meningioma of the 60 year old woman in the genesis of her recurrent complex visual hallucinations. The mass effect directly on the optic chiasm altered the sensory visual input and probably affected network areas between frontal and parietal cortex that are responsible of visual attention top-down signals functions. The authors conclude that the resolution of the atypical visual hallucinations after surgery was not accompanied by a complete resolution of cranial nerves dysfunction that persisted after months after intervention.

Keywords

Visual hallucinations; Depression

Introduction

The case of a 60-year-old woman with depressive symptoms and atypical visual hallucinations is presented. Further investigation pointed out neurological symptoms such as anosmia, dysgeusia and blurred vision: an organic cause was thus suspected. Three extra-axial brain lesions were identified. The hugest tumour was in the medial fronto-basal region and it has been related to the clinic manifestation.

Until now, no previous case report described association of depressive symptoms and visual hallucinations to fronto-temporal meningioma.

A systematic review of case report studies [1] pointed out that visual hallucinations are mostly related to tumours situated in the occipital region [2] or in the cerebello-pontine angle [3-5]. Fronto-temporal meningioma has already been related to anxio-depressive symptoms [6-12]. No link between fronto-temporal lesions and visual hallucination was listed in this review [1].

Visual perceptual disturbances and depersonalization related to a right temporal lobe meningioma were described in a 69-yearsold woman, main psychiatric symptoms were, however, anxiety attacks [13]. A neuroepithelial cyst of the third ventricle simulated a manic recurrent phase with visual hallucinations [14].

Thus, the presented case report may lead to a deeper understanding of the visual hallucinations mechanism and the brain areas involved in this process.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman was admitted to a compulsory psychiatric hospitalization facility for mood and psychotic disorders in an academic hospital.

In the previous 9 months, her general health condition had started to gradually degenerate. A 6 months sick leave was identified as stressor factor from the entourage. Once come back to her job as school janitor, she was reporting to her daughter the feeling to be harassed by colleagues. Thus, she was suggested to retire.

She was presenting the following symptoms increasing progressively: depressed mood, anergy, aboulia, anhedonia, social withdrawal, hostility, and negligence towards her pets and herself (poorer hygiene, unbalanced nutrition, stopping taking her drugs). Neighbours even called the police once because of the stink coming from her flat.

Her daughter offered some home-based professional aid and the family doctor proposed her to be screened or hospitalized. She categorically refused any kind of help. The family doctor asked a psychiatric expertise. The police accompanied her to an agreed Emergency Department beneath the public prosecutor’s office authorization.

The following vital signs were altered: temperature at 37.7 °C and hyperglycaemia, probably related to the lack of compliance of her diabetes medication. The psychiatric team suspected a major depressive episode with melancholic symptoms. She refused every type of medical support. Danger towards herself was certified because of the extreme self-negligence. Hence, it was decided to hospitalize her in a compulsory psychiatric department.

The admission complete collection of data was realized. Vital signs were stable, no pyrexia and normal glycaemic indexes. She was reported to be homogeneous right-handed, French-native speaker.

She was observed older than her age and neglected presentation. She presented indifferent attitude, psychomotor retardation and lack in spatiotemporal steering. Depressed mood and apathy were accompanied by hopelessness. Instinctual functions seemed to be conserved.

Her medical history was the following. She had been treated 2 years previously for tuberculosis. In the past, she underwent two surgical interventions: a subtotal hysterectomy and a total thyroidectomy because of a multinodular goitre.

She was suffering of diabetes and asthmatic bronchitis. She quitted her medical treatment since at least 2 months. No personal and familial psychiatric history was reported. No toxics abuse either. Tobacco consumption: around 20 cigarettes per day.

Both symptoms and clinical history seemed to stick to a characterized major depressive episode.

Nevertheless, a further questioning was led. Visual hallucinations were highlighted: she reported to see plastic cup on the tables, without being emotionally involved about this hallucination. Neither had she criticized it. Her compensative strategy was to look away from the cabinet table during the interview. For the first time, other signs were reported: anosmia, bilateral reduction of visual acuity with blurred vision, dysgeusia and intermittent headache.

An urgent brain imaging was realized. CT-scan and subsequent MRI showed three extra-axial brain lesions.

The most voluminous one was an extra-axial lesion in the fronto-basal area, highly suspected an olfactory meningioma. Dimensions were 67 mm x 62 mm x 51 mm. Consequent mass effect, perilesional oedema, lateral ventricles deformation and protrusion closely to optic chiasm were reported (Figure 1).

The second tumour was described in the left anterior temporal region, measuring 15 x 12 mm. The third was a 6 mm nodular and partly calcified lesion localized right parietal area. They were possibly matching with meningioma, as the first one.

She was transferred to the neurosurgical department the day after. A left pterional craniotomy was realized to practice a Simpson II excision of the olfactive lesion and the left sphenoidal wing. The pathology laboratory confirmed a transitional meningioma grade I OMS 2016. the No genetic basis was enlightened from the analysis. Post-surgery CT-scan excluded any immediate complication.

Clinical evolution was impressive; she rapidly started to self-care, begun ordinary daily activities and kept good relationships with the entourage. She reported to have reacquired interest in life. Slight but non-disturbing hyposmia and hypogeusia were persisting. No focal neurological signs, nor pyrexia neither intracranial hypertension symptoms were reported.

Neurosurgical and imaging follow-up were realized after she was dismissed from the hospital. Ophthalmology check-up objectified persistent reduction of visual function. The patient continued endocrinology follow-up for diabetes and hypothyroidism.

Psychiatric follow-up until few months later the surgery was reassuring. She did not present any residual symptoms, nor hallucination neither mood disorder. Her presentation was clean. She acted friendly, had mobile and concordant facial expression, perfect spatio-temporal steering. She did not present psychomotor impairment. Prosody was coherent and structured. Her instinctual and cognitive functions were intact.

Memories of the morbid period were fragmented. She recalled sporadic events while at home: she described having recurrently seen bugs on her apartment walls, she realized that she was being depressed, hopeless, she recalled suicidal thoughts by gun shooting herself that she verbalized once to her daughter. She reported an amnestic span starting after the psychiatric expertise and lasting all the time she stayed in the psychiatric unit. She reminded having been few days in the neurosurgery department where she recalled having been disinhibited and still presented visual hallucinations (i.e. Santa Claus appearing out of wooden doors). Mnestic functions normally restarted since the day after the surgery.

Discussion

The principal risk factor of olfactory meningioma is ionizing radiation [15-17]. Nor the patient neither her entourage declared any exposure to ionizing radiation during her personal and professional life, she had worked as school janitor. There is a unbalanced 2:1 female/male ratio with a peak ratio of 3.15:1 during peak reproductive years. Exogenous hormone use was suggested to be a risk factor for meningioma [18]. Despite the data correlating hormones with meningioma, they have not been consistently associated with meningioma incidence [15].

In this case, atypical visual hallucinations and depressive symptoms had completely resolved after neurosurgery intervention on the frontobasal olfactory meningioma.

At the beginning, the clinical presentation was strongly suggestive for a typical severe depressive episode. Nevertheless, a complete medical approach to this patient’s symptoms allowed correct diagnose and appropriate treatment. Psychiatric symptoms may be the only presenting feature of brain tumours, even though they are rarely the primary cause of psychiatric symptoms [1].

Association of depressive and behavioural symptoms to frontal region tumours is commonly described in literature; prefrontal cortex neural activity is known to play a crucial role in tasks as sensory input reception (attention), behavioural inhibition and emotional responses [19].

Bilateral visual acuity loss is typical in clinical presentation of cranial base meningioma, via optic nerf compression and intracranial hypertension. It is known as Foster-Kennedy syndrome, in which association with anosmia and ageusia is common [20].

Clinical presentation with atypical visual hallucinations has rarely been reported to be caused by an extra-axial fronto-basal cerebral tumour. One case report study described a frontal tumour initially presenting blindness with visual hallucinations in a 52-year-old woman [21]. In another situation, auditory hallucinations appeared after right frontal meningioma resection in a mid-60s woman have been reported [22].

Neural mechanisms of visual hallucinations are still not completely clear. Mainly two approaches have been described: one explains hallucination with bottom-up sensory information processing deficit; the other approach refers to lack of top-down prior expectation processing in perception [23].

The Perception and Attention Deficit (PAD) model has been proposed for recurrent complex visual hallucinations (RCVH), which refer to hallucinatory repetitive images seen against the background of the existing visual scene occurring during waking state (24). PAD model describes arising of the hallucination when both perceptual (bottom-up) and attentional (topdown) impairments coexist [24,25].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the PAD model as a combination of the classical bottom-up and top-down approaches, allows understanding the double role of the olfactory meningioma of the 60-years-old woman in question in the genesis of her recurrent complex visual hallucinations. From one side, the mass effect directly on the optic chiasm altered the sensory visual input. On the other side, it probably affected network areas between frontal and parietal cortex, that are responsible of visual attention top-down signals functions. Additionally, the resolution of the atypical visual hallucinations after surgery was not accompanied by a complete resolution of cranial nerves dysfunction (i.e. hyposmia, hypogeusia and reduction of visual function persisting months after intervention).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pr. Nicolas Gaspard (Department of Neurology, Erasme Hospital, Brussels, Belgium) for his help with the corrections.

Author orcid

Simone Marchini, https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-0432-5705

References

- Madhusoodanan S, Ting MB, Farah T, et al. Psychiatric aspects of brain tumors: A review. World. J. Psychiatry 5(3), 273 (2015).

- Werring DJ, Marsden CD. Visual hallucinations and palinopsia due to an occipital lobe tuberculoma. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 66(5), 684 (1999).

- Kaloshi G, Alikaj V, Rroji A, et al. Visual and auditory hallucinations revealing cerebellar extraventricular neurocytoma: uncommon presentation for uncommon tumor in uncommon location. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 35(6), 680.e1-3.

- Parisis D, Poulios I, Karkavelas G, et al.Peduncular hallucinosis secondary to brainstem compression by cerebellar metastases. Eur. Neurol 50(2), 107–109 (2003).

- Ball C. The psychiatric presentation of a cerebellopontine angle tumour. Ir. J. Psychol. Med 13(1), 21–23 (1996).

- Assefa D, Haque FN, Wong AH. Case report: anxiety and fear in a patient with meningioma compressing the left amygdala. Neurocase 18(2), 91–94 (2012).

- Goldstein MZ, Richardson C. Meningioma with depression: ECT risk or benefit? Psychosomatics 29(3), 349–351 (1988).

- Greenberg LB, Mofson R, Fink M. Prospective electroconvulsive therapy in a delusional depressed patient with a frontal meningioma. A case report. Br. J. Psychiatry 153: 105–107 (1988).

- Goldstein MZ, Richardson C. Meningioma with depression: ECT risk or benefit? Psychosomatics 29(3), 349–351 (1988).

- Maurice-Williams RS, Sinar EJ. Depression caused by an intracranial meningioma relieved by leucotomy prior to diagnosis of the tumour. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 47(8), 84–85 (1984).

- Lahmeyer HW. Frontal lobe meningioma and depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 43(6), 254–255 (1982).

- Carlson RJ. Frontal lobe lesions masquerading as psychiatric disturbances. Can. Psychiatr. Assoc. J 22(6), 315–318 (1977).

- Ghadirian AM, Gauthier S, Bertrand S. Anxiety attacks in a patient with a right temporal lobe meningioma. J. Clin. Psychiatry 47(5), 270–271 (1986).

- Bhatia MS, Srivastava S, Jhanjee A, et al. Colloid cyst presenting as recurrent mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci 25(3), E01-2 (2013).

- Adappa ND, Lee JYK, Chiu AG, et al. Olfactory Groove Meningioma. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am 44(4), 965–980 (2011).

- Sadetzki S. Genotyping of Patients with Sporadic and Radiation-Associated Meningiomas. Cancer. Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev 14(4), 969–76 (2005).

- Sadetzki S, Flint-Richter P, Ben-Tal T, et al. Radiation-induced meningioma: a descriptive study of 253 cases. J Neurosurg 97(5), 1078–1082 (2002).

- Claus EB, Black PM, Bondy ML, et al. Exogenous hormone use and meningioma risk. Cancer 110(3), 471–476 (2000)

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrate theory of PFC function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 24(1), 167–202 (2001).

- Foster K. Retrobulbar neuritis as an exact diagnostic sign of certain tumors and abscesses in the frontal lobes. Am. J. Med. Sci 142(3), 35 (1911).

- Kosman KA, Silbersweig DA. Pseudo-Charles Bonnet Syndrome With a Frontal Tumor: Visual Hallucinations, the Brain, and the

- Two-Hit Hypothesis. J. Neuropsychiatry. Clin Neurosci 30(1), 84–86 (2017). Coetzer R. Auditory hallucinations secondary to a right frontal meningioma. J. Neuropsychiatry, Clin. Neurosci 26(3), E15 (2014).

- Kumar S, Soren S, Chaudhury S. Hallucinations: Etiology and clinical implications. Ind. Psychiatry. J 18(2), 119–26 (2001).

- Collerton D, Perry E, McKeith I. Why people see things that are not there: a novel Perception and Attention Deficit model for recurrent complex visual hallucinations. Behav. Brain. Sci 28(6), 737–757( 2005).

- Kastner S, Ungerleider LG. Mechanisms of visual attention in the human cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 23(1), 315–41 (2000).