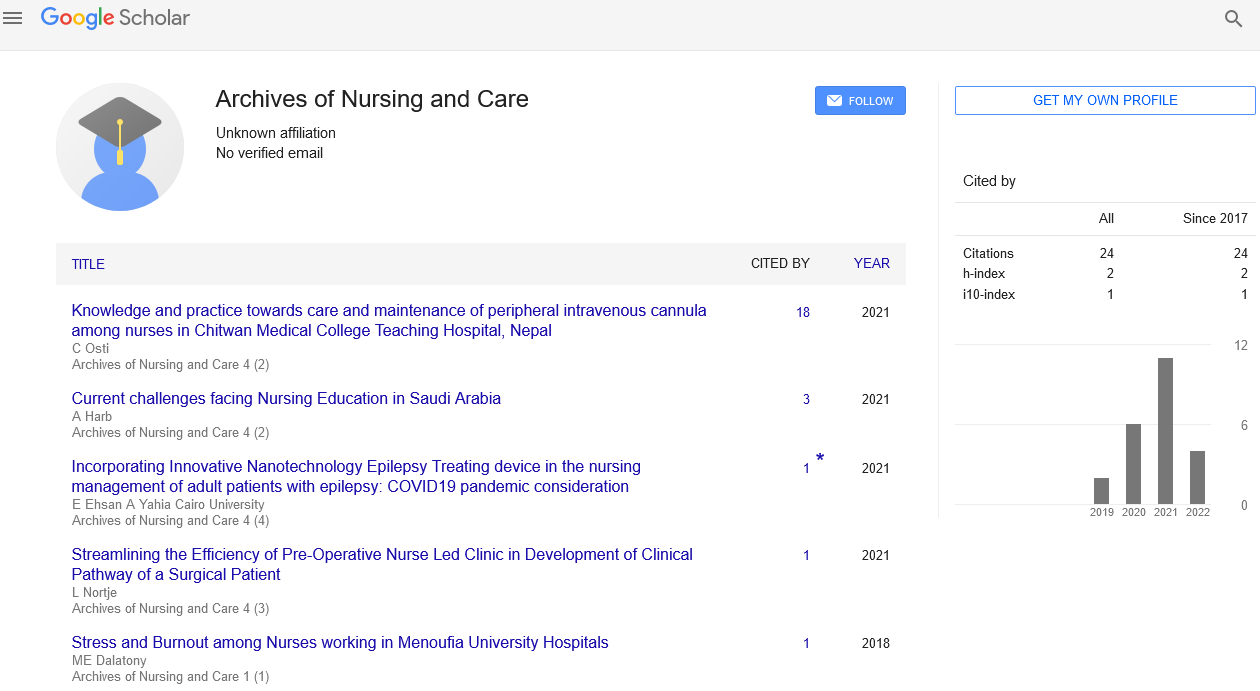

Mini Review - Archives of Nursing and Care (2023) Volume 6, Issue 1

Paediatric palliative care nursing

Rickey Wilson*

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Washington, USA

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Washington, USA

E-mail: wilsonrickey@rediff.com

Received: 02-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. OANC-23-86228; Editor assigned: 04-Jan-2023, PreQC No. OANC-23-86228 (PQ); Reviewed: 18-Jan-2023, QC No. OANC-23- 86228; Revised: 23-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. OANC-23-86228 (R); Published: 30-Jan-2023; DOI: 10.37532/oanc.2023.6(1).010-012

Abstract

For kids with life-threatening illnesses and their families, palliative care is a type of patient- and family-centered care that improves quality of life throughout the course of the illness and can lessen symptoms, discomfort, and stress. In order to improve life and lessen suffering for these kids and their families, this paper intends to raise nurses' and other healthcare professionals' awareness of a few recent research endeavours. Based on gaps in the literature on paediatric palliative care, topics were chosen. Selected elements of paediatric palliative nursing care, such as (I) examples of interventions (legacy and animal-assisted interventions); (II) international studies (parent-sibling bereavement, continuing bonds in Ecuador, and circumstances surrounding deaths in Honduras); (III) recruitment techniques; (IV) communication among paediatric patients, their parents, and the healthcare team; (V) training in paediatric palliative nursing, were described using published articles and authors' ongoing research. Nurses are in a prime position to support the community, promote the science of paediatric palliative care, and offer palliative care for children at the bedside.

Keywords

Hospice and palliative care nursing • palliative care • palliative nursing • paediatric nursing

Introduction

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary approach to medical care that aims to improve quality of life and lessen suffering for individuals with chronic, complex, and frequently terminal illnesses. The term comes from the Latin word palliare, which means "to cloak." There are numerous definitions of palliative care in the published literature. Palliative care is "an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering through early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual." This is how the World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care. Palliative care used to be a disease-specific strategy, but the WHO now takes a broader perspective and believes that the concepts of palliative care should be implemented as early as possible to any chronic and eventually fatal illness [1-5]. Any age group with a serious illness can get palliative care, either as the primary purpose of care or in conjunction with curative therapy. An interdisciplinary team that may consist of doctors, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, psychologists, social workers, chaplains, and nutritionists provides it. Numerous locations, including hospitals, outpatient clinics, skilled nursing facilities, and private homes, can offer palliative care. Palliative care is not only for those who are approaching the end of life, although being a crucial component of end-of-life care [6-8].

Discussion

The effectiveness of a palliative care approach in enhancing a person's quality of life is supported by evidence. The primary goal of palliative care is to enhance the quality of life for those with chronic illnesses. Palliative care is frequently given to patients who are nearing the end of their lives, but it can be beneficial for anyone at any age or critical illness stage.

Paediatric palliative care

Paediatric palliative care focuses on minimising the physical, mental, psychological, and spiritual pain associated with sickness in order to ultimately improve quality of life. It is a family-centered, specialist medical service for kids with life-threatening illnesses.

Paediatric palliative care specialists receive specialised training in family-centered, developmental, and age-appropriate communication skills, facilitation of shared decision making, assessment and management of pain and distressing symptoms, advanced knowledge in care coordination of multidisciplinary paediatric caregiving medical teams, referral to hospital and ambulatory resources available to patients and families, and psychologically supporting kids and families [9-10].

Symptoms assessment and management of children

In paediatric palliative care, as in adult palliative care, symptom assessment and management are crucial because they enhance quality of life, provide kids and families a sense of control, and in some situations, extend life. A palliative care team's general methodology for evaluating and treating distressing symptoms in children is as follows:

• Determine and evaluate symptoms by taking a history (focusing on location, quality, time course, as well as exacerbating and mitigating stimuli). Due to communication limitations and the child's limited capacity for symptom identification and communication, symptom assessment in youngsters presents a special set of difficulties. Therefore, the clinical history should be provided by both the kid and the caretakers. Having said that, children as young as four years old may express the location and intensity of pain using metaphors and visual mapping techniques.

• Conduct a complete examination of the child. Pay close attention to how the kid behaves in reaction to exam elements, especially in light of any potentially painful stimuli. According to research, pain perception in preterm and newborn children is equal to or greater than that of adults, contrary to the widely held belief that these age groups do not sense pain because their pain pathways are still developing. Having said that, some kids with excruciating pain exhibit 'psychomotor inertia,' a condition in which a kid with extreme chronic pain exhibits excessive good behaviour or depression. When the dosage of morphine is increased, these patients exhibit behavioural reactions that are consistent with pain alleviation. Last but not least, a child who is playing or sleeping should not be taken for granted as being painfree because of the way children behave in response to discomfort.

• Identify the treatment facility (tertiary versus local hospital, intensive care unit, home, hospice, etc.).

• Based on the anticipated diagnosis' theorised illness course, anticipate symptoms.

• In advance, discuss treatment alternatives with the family based on the resources and care options offered in the aforementioned care settings. To provide smooth continuity of service delivery across health, education, and social care contexts, subsequent management should prepare for transfers of palliative care settings.

• When treating distressing symptoms, take into account both pharmaceutical and non-pharmacological treatment options (such as education, mental health support, the use of hot and cold packs, massage, play therapy, distraction therapy, hypnotherapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and complementary therapies). The added practise of respite care can help the child and its family's physical and emotional suffering. It gives the family time to rest and recharge by allowing the caregiving to be carried out by other qualified people.

• To develop tailored care plans, consider the child's perspective on their symptoms (based on their own experiences).

• Include the child and family in the re-evaluation of symptoms once the therapeutic strategies have been put into place.

Conclusions

The nurses play a big part in taking care of kids who have life-threatening illnesses or who are already dying from them. The science of paediatric palliative nursing care needs to be further developed in order to better understand how to prolong life and lessen suffering for these defenceless kids and their families, who are at a high risk of adverse outcomes. The field is generally prepared to extend study populations to include non-cancer diseases and to transition from descriptive to therapeutic work. To further enhance the science of paediatric palliative care, nursing researchers must take the initiative and pave the path for the creation and execution of rigorous interdisciplinary studies. Paediatric palliative care nurse researchers must take advantage of funding opportunities, such as the National Institute of Nursing Research funding for palliative care and EOL research, seek leadership positions within national palliative care organisations, such as the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, and mentor students and junior scientists to create the next generation. To provide the greatest clinical care to children and their families and to support the community at large, it is crucial to pay more attention to better preparing nurses at the bedside and other healthcare workers in paediatric palliative care. Finally, nurses are in a prime position to close any gaps that may exist between specialists from different fields, kids and their families, researchers and clinicians, students and role models, local governments, and politicians so that we can all work together to improve the lives of kids with life-threatening conditions and their families.

References

- Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. The Lancet. 371, 852-864 (2008).

- Williams‐Reade J, Lamson AL, Knight SM, et al. Paediatric palliative care: a review of needs, obstacles and the future. Journal of Nursing Management. 23, 4-14 (2015).

- Hill K, Coyne I. Palliative care nursing for children in the UK and Ireland. British journal of nursing. 21, 276-281 (2012).

- Couch E, Mead JM, Walsh MM. Oral health perceptions of paediatric palliative care nursing staff. International journal of palliative nursing. 19, 9-15 (2013).

- Harrop E, Edwards C. How and when to refer a child for specialist paediatric palliative care. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Education and Practice. 98, 202-208 (2013).

- Armitage N, Trethewie S. Paediatric palliative care-the role of the GP. Australian Family Physician. 43, 176-180 (2014).

- Wood F, Simpson S, Barnes E et al. Disease trajectories and ACT/RCPCH categories in paediatric palliative care. Palliative Medicine. 24, 796-806 (2010).

- O’Leary N, Flynn J, MacCallion A et al. Paediatric palliative care delivered by an adult palliative care service. Palliative Medicine. 20, 433-437 (2006).

- Jünger S, Vedder AE, Milde S et al. Paediatric palliative home care by general paediatricians: a multimethod study on perceived barriers and incentives. BMC palliative care. 9, 1-12 (2010).

- Vadeboncoeur CM, Splinter WM, Rattray M et al. A paediatric palliative care programme in development: trends in referral and location of death. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 95, 686-689 (2010).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref