Review Article - Interventional Cardiology (2009) Volume 1, Issue 1

Percutaneous coronary intervention for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis

- Corresponding Author:

- Seung-Jung Park

Cardiac Center, Asan Medical Center

University of Ulsan, 388-1 Pungnap-dong

Songpa-gu, Seoul, 138-736, Korea

Tel: +82 230 104 812

Fax: +82 24 86 5918

E-mail: sjpark@amc.seoul.kr

Abstract

Keywords

bypass surgery, coronary artery, left main, prognosis, restenosis, stent

Owing to the long-term benefit of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery compared with medical therapy, CABG has been the standard treatment for unprotected left main coronary artery (LMCA) stenosis [1–3]. However, with advances in technique and equipment, the percutaneous interventional approach for implantation of coronary stents has been shown to be feasible for patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis [3]. In particular, the recent introduction of drug-eluting stents (DES), together with advances in periprocedural and postprocedural adjunctive pharmacotherapies, have improved outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) for these complex coronary lesions [4–29]. Nonetheless, PCI for unprotected LMCA stenosis is still only indicated for patients at a high surgical risk or for emergent clinical situations, such as bailout procedure or acute myocardial infarction (MI), as an alternative therapy to CABG, as the recent registry and randomized study failed to prove superiority, or at least noninferiority, of DES placement for unprotected LMCA stenosis, as compared with CABG [21,30,31]. By contrast, there is concern regarding the long-term safety of DES. The incidence of late stent thrombosis has been reported to be higher with DES compared with bare-metal stent (BMS) implantation [32–36]. Indeed, the US FDA has warned that the risk of stent thrombosis may outweigh the benefits of DES in off-label use, such as for unprotected LMCA stenosis [37]. Therefore, in this review, we evaluate the current techniques and outcomes of PCI with either BMS or DES compared with CABG in a series of studies conducted in several countries.

Significant left main coronary artery stenosis

Coronary angiography has been the standard tool to determine the severity of coronary artery disease. Although a traditional cut-off for significant coronary stenosis has been diameter stenosis of 70% in non-LMCA lesions, its cutoff in LMCA has been a diameter stenosis of 50%. However, because the conventional coronary angiogram is only a lumenogram, providing information regarding lumen diameter but yielding little insight into lesion and plaque characteristics themselves, it has several limitations due to peculiar anatomic and hemodynamic factors. In addition, the LMCA segment is the least reproducible of any coronary segment with the largest reported intra- and inter-observer variabilities [38–40]. Therefore, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is often used to assess the severity of LMCA stenosis.

A diagnosis of significant stenosis at the LMCA necessitating revascularization should be determined by the absolute luminal area, not by the degree of plaque burden or area stenosis. Because of remodeling, a larger plaque burden can exist in the absence of lumen compromise [41]. Abizaid et al. reported 1‑year follow-up in 122 patients with LMCA disease. The minimum lumen diameter by IVUS was the most important predictor of cardiac events, with a 1‑year event rate of 14% in patients with a minimum luminal diameter of less than 3.0 mm [42]. Fassa et al. reported that the longterm outcome of patients with a LMCA with a minimum lumen area of less than 7.5 mm2 without revascularization were considerably worse than those who were revascularized [43]. Jasti et al. compared fractional flow reserve (FFR) and IVUS in patients with an angiographically ambiguous LMCA stenosis [44]. However, accurate assessment for ostial LMCA is not always possible. Practically, it is important to keep the IVUS catheter co-axial with the LMCA and to disengage the guiding catheter from the ostium so that the guiding catheter is not mistaken for a calcific lesion with a lumen dimension equal to the inner lumen of the guiding catheter. When assessing distal LMCA disease, it is important to begin imaging in the most co-axial branch vessel. Nevertheless, distribution of plaque in the distal LMCA is not always uniform, and it may be necessary to image from more than one branch back into the LMCA.

Fractional flow reserve may play an adjunctive role in determining significant stenosis at the LMCA. FFR is the ratio of the maximal blood flow achievable in a stenotic vessel to the normal maximal flow in the same vessel [45]. An FFR value of less than 0.75 is considered to be a reliable indicator of significant stenosis producing inducible ischemia [46]. In patients with an angiographically equivocal LMCA stenosis, a strategy of revascularization versus medical therapy based on an FFR cut-point of 0.75 was associated with excellent survival and freedom from events for up to 3 years follow-up [44].

Outcomes with DES

▪ Safety compared with BMS

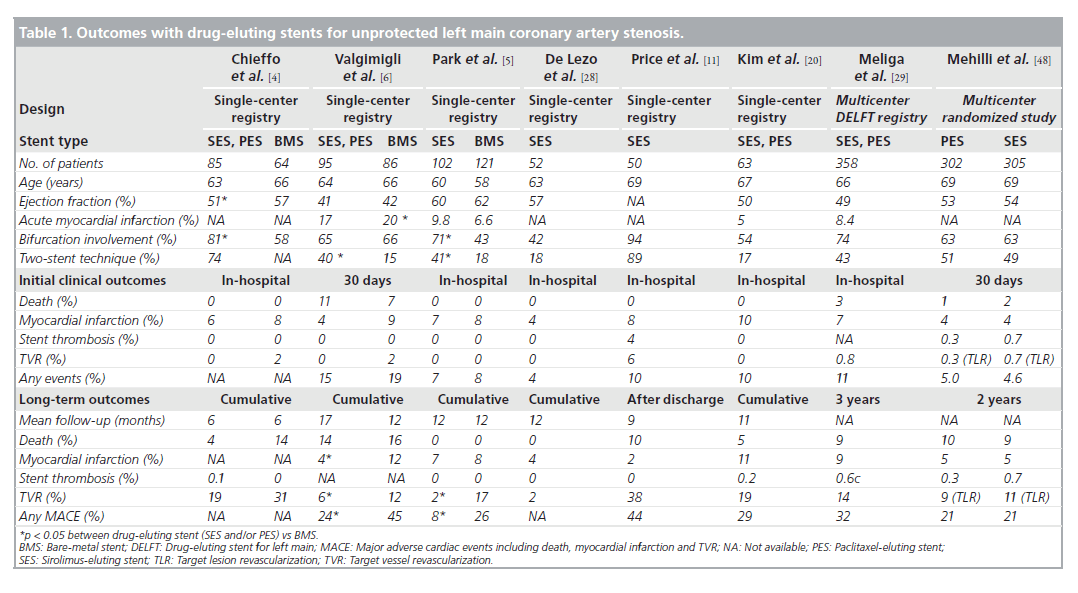

Although there are disputes regarding the longterm safety of DES, the possibility of late or very late thrombosis has still been the major factor limiting global use of DES, especially for unprotected LMCA stenosis. Table 1 depicts the results of recent studies demonstrating the outcomes of DES implantation for unprotected LMCA stenosis. It is clear that none of the clinical studies showed a significant increase in the cumulative rates of death or MI in DES implantation for unprotected LMCA, as compared with BMS. In the three early pilot studies comparing the outcomes of DES with those of BMS, the incidences of death, MI or stent thrombosis were comparable in the two stent types during the procedure and at follow-up [4–6]. Of interest, in the study of Valgimigli et al., DES were associated with significant reductions in both the rate of MI (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.22; p = 0.006) and the composite of death or MI (HR: 0.26; p = 0.004) compared with BMS [6]. Considering that restenosis can lead to an acute MI in 3.5–19.4%, a significant reduction of restenosis achieved by DES might contribute to the better outcome. In fact, a previous study suggested that the episode of restenosis at the BMS in LMCA could present as late mortality [47]. In addition, more frequent repeat revascularization to treat BMS restenosis, in which CABG is the standard of care at the unprotected LMCA, may also be related to the increase in hazardous accidents compared with DES. A recent meta-analysis supported the safety of DES, showing that DES did not increase the risk of death, MI or stent thrombosis compared with BMS [18]. In this meta-analysis of 1278 patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis, for a median of 10 months, mortality rate in DES-based PCI was only 5.5% (3.4 –7.7%) and was not higher than BMS-based PCI.

Table 1. Outcomes with drug-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis.

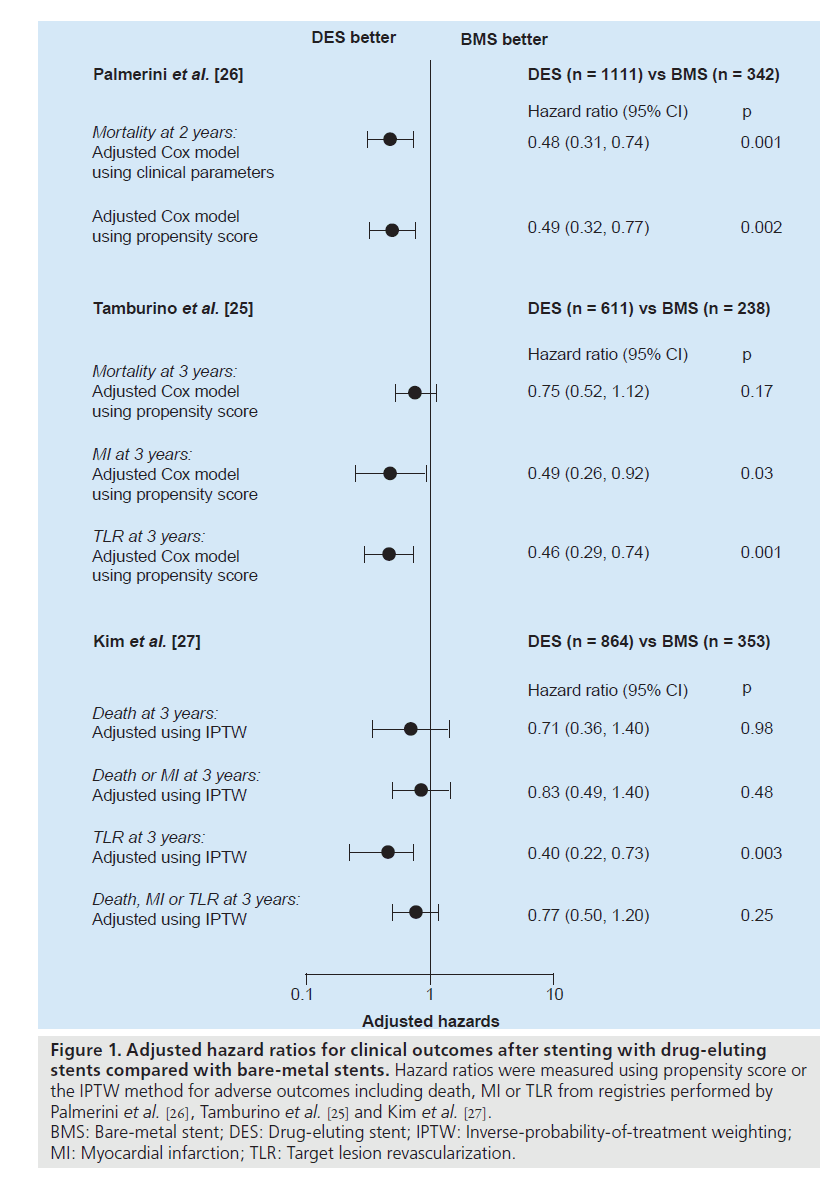

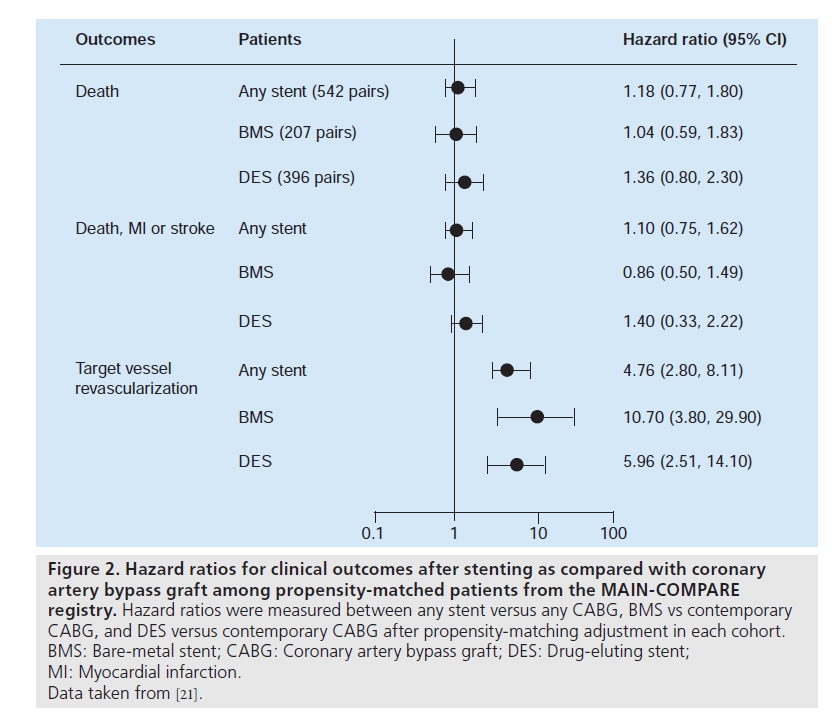

Recently, three registry studies assessed the risk of safety outcomes with the use of DES compared with BMS over 2 years, as shown in Figure 1 [25–27]. After rigorous adjustment using propensity score or the inverse-probability-oftreatment weighting method to avoid selection bias, which was an inherent limitation of the registry study, DES was not associated with long-term increases in death or MI. Of interest, the report of Palmerini et al. showed the survival benefit of DES over 2 years. These studies supported the previous pilot studies that elective PCI with DES for unprotected LMCA stenosis seems to be a safe alternative to CABG.

Figure 1. Adjusted hazard ratios for clinical outcomes after stenting with drug-eluting stents compared with bare-metal stents. Hazard ratios were measured using propensity score or the IPTW method for adverse outcomes including death, MI or TLR from registries performed by Palmerini et al. [26], Tamburino et al. [25] and Kim et al. [27]. BMS: Bare-metal stent; DES: Drug-eluting stent; IPTW: Inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting; MI: Myocardial infarction; TLR: Target lesion revascularization.

Regarding the risk of stent thrombosis, in the series of LMCA DES studies, the incidence of stent thrombosis at 1 year ranged from 0 to 4% and was not statistically different from that in BMS [4–6]. Recently, a multicenter study confirmed the finding that the incidence of definite stent thrombosis at 2 years was only 0.5% in 731 patients treated with DES [19]. In addition, the Drug Eluting Stent for Left Main (DELFT) multicenter registry, which included 358 patients undergoing LMCA stenting with DES, reported that the incidence of definite, probable and possible stent thrombosis was 0.6, 1.1 and 4.4% at 3 years, respectively [29]. In recent large, multicenter studies in (the Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Drug-Eluting Stents for Unprotected Coronary Left Main Lesions [ISAR-LEFT-MAIN] or the Comparison of Percutaneous Coronary Angioplasty Versus Surgical Revascularization [MAINCOMPARE]), the incidence of definite or probable stent thrombosis was less than 1% [21,48].

However, because these studies are still underpowered to completely exclude the possibility of increased risk of stent thrombosis in the long term, further studies need to be performed to determine this. The previous studies assessing the long-term outcomes of DES for complex lesions showed various outcomes. For example, recent large registries evaluating the safety of DES for complex lesions showed comparable risks of death or MI for the two stent types [49,50]. The recent large National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) registry in the USA reported that the off-label use of DES, compared with BMS, for similar indications was associated with a comparable 1‑year risk of death and a lower 1‑year risk of MI after adjustment [49]. Of interest, a large registry of 13,353 patients in Ontario found that the 3‑year mortality rate in a propensity-matched population was significantly higher with BMS than with DES [50]. The comparable or lower incidence of death or MI with the use of DES compared with BMS may be due, at least in part, to the off-setting risks of restenosis versus stent thrombosis.

▪ Risk stratification of long-term safety

Several attempts have been made to predict longterm outcomes of complex LMCA intervention. Predictably, periprocedural and long-term mortality depend strongly on the patient’s clinical presentation. In the Unprotected Left Main Trunk Investigation Multicenter Assessment (ULTIMA) multicenter registry, which included 279 patients treated with BMS, 46% of whom were inoperable or a high surgical risk, the inhospital mortality was 13.7% and the 1‑year incidence of all-cause mortality was 24.2% [51]. On the other hand, in the 32% of patients at low surgical risk (age <65 years and with an ejection fraction >30%), there were no periprocedural deaths and the 1‑year mortality was 3.4%. Similarly, with DES implantation, high surgical risk represented by high EuroSCORE or Parsonnet score was an independent predictor of death or MI [13,52]. Therefore, it is recommended that a lot of attention should continue to be paid to procedure in patients at high surgical risk. More recently, the Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery score (SYNTAX), an angiographic risk stratification model, has been created to predict longterm outcomes after coronary revascularization with either PCI or CABG [30]. In the recent SYNTAX study comparing PCI with paclitaxeleluting stent versus CABG for multivessel or LMCA disease, there was significant interaction between the treatment type and the SYNTAX score [30]. In patients with a high SYNTAX score, CABG, as compared with stenting, had a better outcome in terms of the incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Therefore, for patients with high clinical risk profiles or complex lesion morphologies who are defined using these risk stratification models, PCI procedures need to be performed by experienced interventionalists with the aid of IVUS, mechanical hemodynamic support and optimal adjunctive pharmacotherapies, after the judicious selection of patients.

▪ Restenosis & repeat revascularization

Compared with BMS, DES reduced the incidence of angiographic restenosis and subsequently the need for repeat revascularization in unprotected LMCA stenosis. In the early pilot studies, the 1‑year incidence of repeat revascularization in DES implantation was 2–19% as compared with 12–31% in BMS (Table 1) [4–6]. Fortunately, in the long-term study up to 3 years, the incidence of repeat revascularization remained steady without the significant observation of ‘late catchup’ phenomenon of late restenosis noted after coronary brachytherapy [21]. Recently, two larger registries confirmed the efficacy of DES [25,27]. The risk of target lesion revascularization over 3 years was reduced by 60% with use of DES as shown in Figure 1 [27].

The risk of restenosis was significantly influenced by lesion location. DES treatment for the ostial and shaft LMCA lesions had a very low incidence of angiographic or clinical restenosis [14]. In a study including 144 patients with ostial or shaft stenosis in three cardiac centers, angiographic restenosis and target vessel revascularization at 1 year occurred in only one (1%) and two (1%) patients, respectively. Although the lack of availability of DES sizes bigger than 3.5 mm imposed an overdilation strategy to match LMCA reference diameter, there was no incidence of cardiac death, MI or stent thrombosis in this study.

By contrast, PCI for LMCA bifurcation has been more challenging, although prevalence was more than 60% across the previous studies [4–6,10,21]. However, repeat revascularization was exclusively performed in patients with PCI for bifurcation stenosis [4–6]. A recent study assessing the outcomes of LMCA DES showed that the risk of target vessel revascularization was sixfold higher (95% CI: 1.2–29) in bifurcation stenosis compared with nonbifurcation stenosis (13 vs 3%) [13]. The risk of bifurcation stenosis was further highlighted in a recent study of Price et al., which showed that the target lesion revascularization rate after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation was 44% [11]. In this study, 94% (47 out of 50) of patients had lesions at the bifurcation and 98% underwent serial angiographic follow-up at 3 and/or 9 months. This discouraging result led to caution over the efficacy of DES and highlighted the need for meticulous surveillance of angiographic follow-up in PCI for LMCA bifurcation stenosis. However, this study was limited by the exclusive use of a complex stenting strategy (two stents in both branches) in 84% of patients, which may increase the need for repeat revascularization. Although there was a debate [53], a current report suggested the probability that the complex stenting technique might be associated with a high occurrence of restenosis compared with the simple stenting technique [8]. A subgroup analysis of the large Italian registry supported this with the hypothesis that a single stenting strategy for bifurcation LMCA lesions had comparable longterm outcomes with nonbifurcation lesions [24]. Taken together, before a novel treatment strategy is settled, the simple stenting approach (LMCA to left anterior descending artery with optional treatment in the circumflex artery) is primarily recommended in patients with a relatively patent or diminutive circumflex artery. Furthermore, future stent platforms specifically designed for LMCA bifurcation lesions may provide better scaffolding and more uniform drug delivery to the bifurcation LMCA stenosis.

Regarding the differential benefit of DES for the prevention of restenosis, the two most widely applicable DES – sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents – were evaluated in previous studies. An early study comparing the two DES from a RESEARCH registry showed a comparable incidence of major adverse cardiac events with 25% in sirolimus- (55 patients) and 29% in paclitaxeleluting stents (55 patients) [12]. The recent ISARLEFT- MAIN study compared 305 patients receiving sirolimus- and 302 patients receiving paclitaxel-eluting stents with a prospective randomized design [48]. At 1 year, major adverse events occurred in 13.6% of the paclitaxel- and 15.8% of the sirolimus-eluting stent groups with 16.0 and 19.4% restenosis, respectively (p = not significant). Use of second-generation DES is being evaluated in many studies.

Comparison with CABG

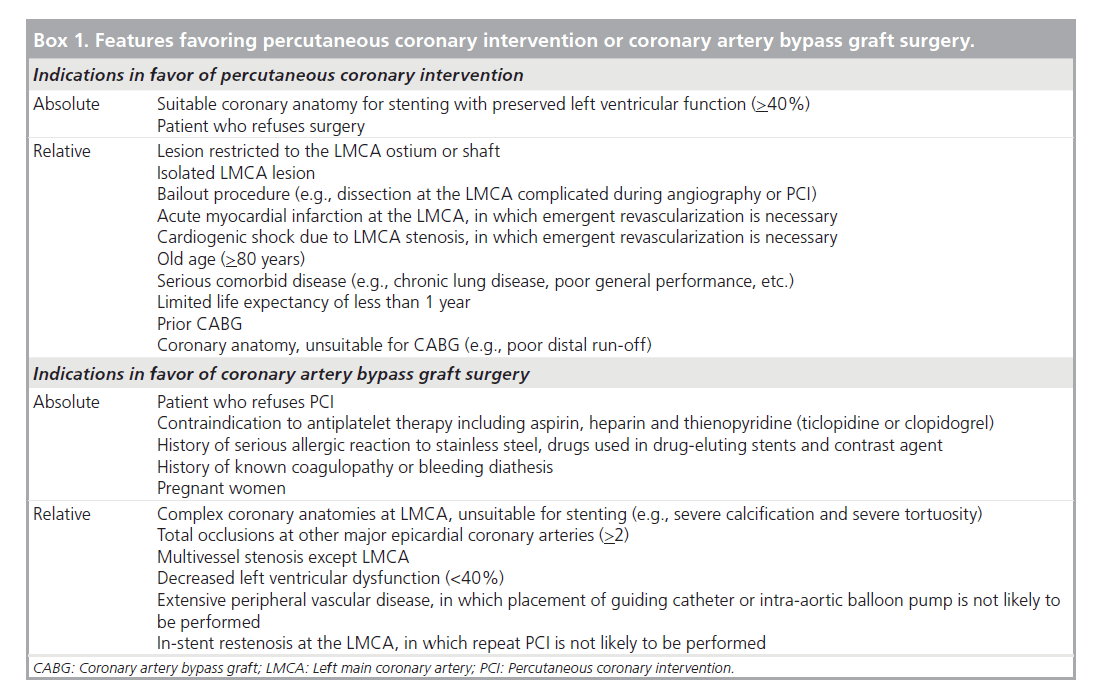

It is surprising to note that current guidelines for the treatment of unprotected LMCA, in which elective PCI for patients who are treatable with bypass surgery is a contraindication, are based mostly on 20‑year-old clinical trials [1–3]. These studies demonstrated a definite benefit in survival of CABG in LMCA stenosis compared with medical treatment. However, the application of these results to current practice seems inappropriate as surgical technique as well as medical treatment in these studies is outdated by current standards and no randomization studies between PCI and CABG with enough power have been conducted. The lack of data on the current CABG procedure used in unprotected LMCA stenosis further precludes a theoretical comparison of the two revascularization strategies. Box 1 lists the patient and lesion characteristics favoring PCI or CABG based on current expert opinion and evidence.

Box 1. Features favoring percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

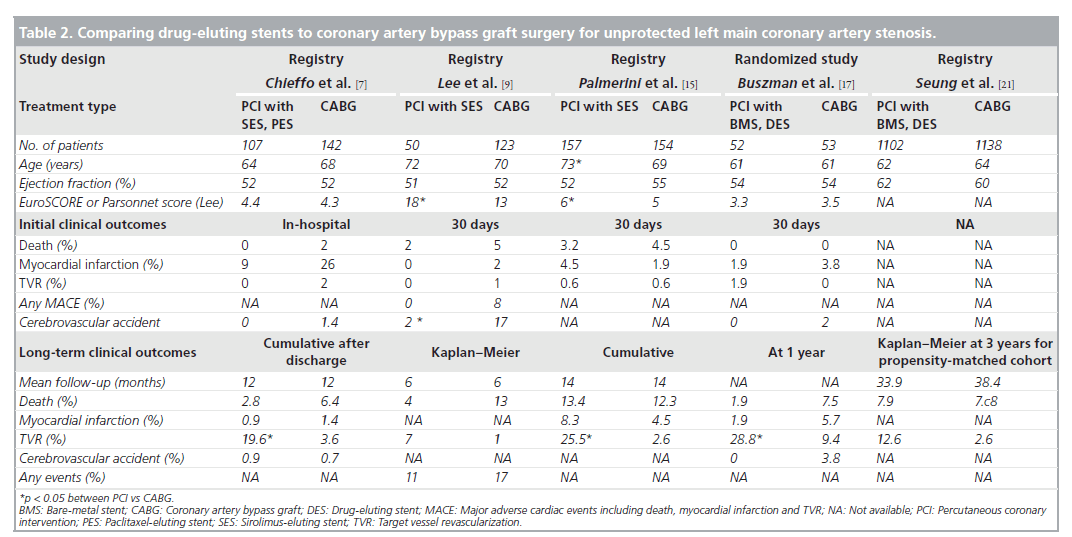

Currently, several nonrandomized studies comparing the safety and efficacy of DES treatment for unprotected LMCA stenosis, compared with CABG, have been published (Table 2). Chieffo et al. retrospectively compared the outcomes of 107 patients undergoing DES placement with 142 patients undergoing CABG [7]. They showed that DES was associated with a nonsignificant benefit in mortality (OR: 0.331; p = 0.167) and significantly lower incidence of composites of death or MI (OR: 0.260; p = 0.0005) and death, MI or cerebrovascular accident (OR: 0.385; p = 0.01) at 1‑year followup. Conversely, CABG was correlated with a lower occurrence of target vessel revascularization (3.6 vs 19.6%; p = 0.0001). These findings were supported by the report of Lee et al., which consisted of 50 patients with DES placement and 123 patients with CABG [9]. In this study, although the DES group had a slightly higher surgical risk, the rate of mortality or MI at 30 days was comparable between the two treatments. At 1‑year follow-up, the DES had nonsignificantly better clinical outcomes compared with CABG, reflected in overall survival (96 vs 85%) and survival freedom from death, MI, target vessel revascularization or adverse cerebrovascular events (83 vs 75%). However, the survival freedom from repeat revascularization at 1 year remained nonsignificantly higher for the CABG compared with the DES (95 vs 87%). The results of a recent multicenter registry were in agreement with the previous two reports with regards to the safety outcomes [10]. The PCI group treated with BMS or DES (60%) had a similar incidence of death and/or MI, but a higher incidence of target lesion revascularization compared with the CABG group. A similarity in safety with the use of PCI compared with CABG was ascertained for older patients (age >75 years) by Palmerini et al. [15]. Recently, a randomized study comparing PCI (n = 52) with CABG (n = 53) was undertaken for 105 patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis [17]. PCI was performed using either BMS (65%) or DES (35%). The primary end point was the change in left ventricular ejection fraction 12 months after the intervention, in which a significant increase in ejection fraction was noted only in the PCI group (3.3 ± 6.7% after PCI vs 0.5 ± 0.8% after CABG; p = 0.047). By contrast, at 1 year after procedure, repeat revascularization was significantly lower in the CABG group (n = 5) than in the PCI group (n = 15), although the incidence of death or MI was comparable between the two groups. However, this study was still underpowered to assess the long-term clinical effectiveness of PCI compared with CABG. Stronger evidence for the feasibility of PCI as an alternative to CABG comes from the recent large registry, the MAIN-COMPARE study [21]. They analyzed data from 2240 patients with unprotected LMCA disease treated at 12 medical centers in Korea. Of these, 318 were treated with BMS, 784 were treated with DES and 1138 underwent CABG. To avoid bias due to the nonrandomized study design, a novel adjustment was performed using propensityscore matching in overall population and separate periods. In the first and second waves, BMS and DES were exclusively used, respectively. The outcomes of stenting in the overall patients and each wave were compared with those of concurrent CABG as shown in Figure 2. During 3 years of follow-up, patients treated with stenting were nearly four-times as likely to need a repeat revascularization when compared with those who underwent CABG (HR: 4.76; 95% CI: 2.80– 8.11). However, the rates of death (HR: 1.18; 95% CI: 0.77–1.80) and the combined rates of death, MI and stroke (HR: 1.10; 95% CI: 0.75– 1.62) were not significantly higher with the use of stenting compared with CABG, as shown in Figure 1. A similar pattern was also observed in patients treated with DES or BMS. Another interesting finding in this study was that the majority of repeat revascularization in PCI patients were treated with repeat PCI instead of CABG. Given the fact that the recommendation for CABG for unprotected LMCA disease has been based mostly on survival benefit compared with medical treatment, the lack of a statistically significant difference in mortality may support PCI as an alternative option to bypass surgery. In addition, a current recommendation of routine angiographic surveillance at 6–9 months after PCI for unprotected LMCA stenosis might increase unnecessary repeat revascularization due to the ‘oculo-stenotic’ reflex.

Table 2. Comparing drug-eluting stents to coronary artery bypass graft surgery for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis.

Figure 2. Hazard ratios for clinical outcomes after stenting as compared with coronary artery bypass graft among propensity-matched patients from the MAIN-COMPARE registry. Hazard ratios were measured between any stent versus any CABG, BMS vs contemporary CABG, and DES versus contemporary CABG after propensity-matching adjustment in each cohort. BMS: Bare-metal stent; CABG: Coronary artery bypass graft; DES: Drug-eluting stent; MI: Myocardial infarction. Data taken from [21].

The ultimate proof of the relative values of PCI versus CABG for unprotected LMCA stenosis clearly depends on the results of randomized clinical trials comparing the two treatment strategies. The trials will involve a number of technical considerations that could significantly alter angioplasty outcomes. The SYNTAX trial compared the outcomes of PCI with paclitaxeleluting stents versus CABG for unprotected LMCA stenosis in a subgroup analysis from the randomized study cohort [30]. As shown in the subset of LMCA disease comprising 348 patients receiving CABG and 357 receiving PCI, PCI (15.8%) demonstrated equivalent 1‑year clinical outcomes compared with CABG (13.7%; p = 0.44). Of interest was the fact that the higher rate of repeat revascularization with the use of PCI (11.8 vs 6.5%; p = 0.02) was offset by a higher incidence of stroke with the use of CABG (2.7 vs 0.3%; p = 0.01). However, it should be noted that the analysis for LMCA disease was not the primary objective analysis but the post hoc analysis, which was hypothesisgenerating. Therefore, a further randomized study is warranted to provide a confirmative answer to the question of a specific cohort of patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis. Another randomized study, the Premier of Randomized Comparison of Bypass Surgery versus Angioplasty using Sirolimus-Eluting Stent in Patients with Left Main Coronary Artery Disease (PRECOMBAT) trial, is being performed in Korea randomizing 600 patients with unprotected LMCA patients with either CABG or PCI with sirolimus-eluting stents. This study is a noninferiority design with the primary end point of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at a mean of 2 years.

Technical considerations

▪ Stenting procedure

Stenting for ostial or body LMCA lesions appears to be a simple alternative stenting technique for nonbifurcation LMCA coronary lesions. For instance, a brief and maximal stent expansion is required to get optimal stent expansion and to avoid ischemic complication. In ostial LMCA lesions, the coronary stent is generally positioned outside the LMCA for complete lesion coverage of the ostium. Stenting for bifurcation LMCA lesions, however, is more complex and technically demanding. In general, the selection of an appropriate stenting strategy is dependent on the plaque configuration surrounding the LMCA. However, despite recent randomized studies comparing singlestent versus two-stent treatments for bifurcation coronary lesions [54,55], the optimal stenting strategy for LMCA bifurcation lesions has not yet been determined. A current consensus is that the two-stent strategy does not have longterm advantages in terms of the incidence of any major cardiac events compared with the single-stent strategy. Therefore, systemic treatment with a two-stent strategy for all LMCA bifurcation lesions, such as T-stenting, Kissing stenting, the Crush technique or Culotte technique, is not generally recommended. Instead, a provisional stenting strategy should be considered as the first-line treatment for LMCA bifurcations without significant side-branch stenosis.

▪ Intravascular ultrasound

Intravascular ultrasound is considered to be a useful invasive diagnostic modality in determining anatomical configuration, selecting treatment strategy and defining optimal stenting outcomes in either the BMS or DES era [56]. Although a retrospective study suggested that the clinical impact of IVUS-guided stenting for LMCA with DES did not show a significant clinical long-term benefit compared with angiography-guided procedure [57], the usefulness of IVUS guided-stenting may not be hampered by this underpowered retrospective study. The information gathered by IVUS may be crucial for optimal stenting procedure in unprotected LMCA stenosis. In fact, angiography is limited in assessing the true luminal size of the LMCA because the left main artery is often short and lacks a normal segment for comparison. Therefore, the severity of LMCA stenosis is often underestimated by the misinterpretation of the normal segment adjacent to the focal stenosis. In addition to the actual assessment of LMCA lesions before the procedure, use of IVUS is very helpful to get an adequate expansion of the DES, to prevent stent inapposition and to achieve full lesion coverage with the DES.

A recent subgroup analysis from the MAINCOMPARE registry reported the very interesting finding that IVUS guidance was associated with improved long-term mortality compared with conventional angiography-guided procedures [23]. With an adjustment using propensity- score matching, for 201 matched pairs, there was a strong tendency to lower risk of 3‑year mortality with IVUS guidance compared with angiography guidance (6.3 vs 13.6%; log-rank p = 0.063; HR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.28–1.03). In particular, for 145 pairs of patients receiving DES, the 3‑year incidence of mortality was lower with IVUS guidance compared with angiography guidance (4.7 vs 16.0%; log-rank p = 0.048; HR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.15–1.02). Of interest, mortality started to diverge beyond 1 year. Therefore, despite inherent limitations of nonrandomized registry design, this study indicates that IVUS guidance may play a role in reducing very late stent thrombosis and subsequent long-term mortality. In fact, IVUS evaluations of stent underexpansion, incomplete lesion coverage, small stent area, large residual plaque and inapposition have been found to predict stent thrombosis after DES placement [58–62]. Therefore, we strongly recommend the mandatory use of IVUS in PCI for unprotected LMCA.

▪ Debulking atherectomy

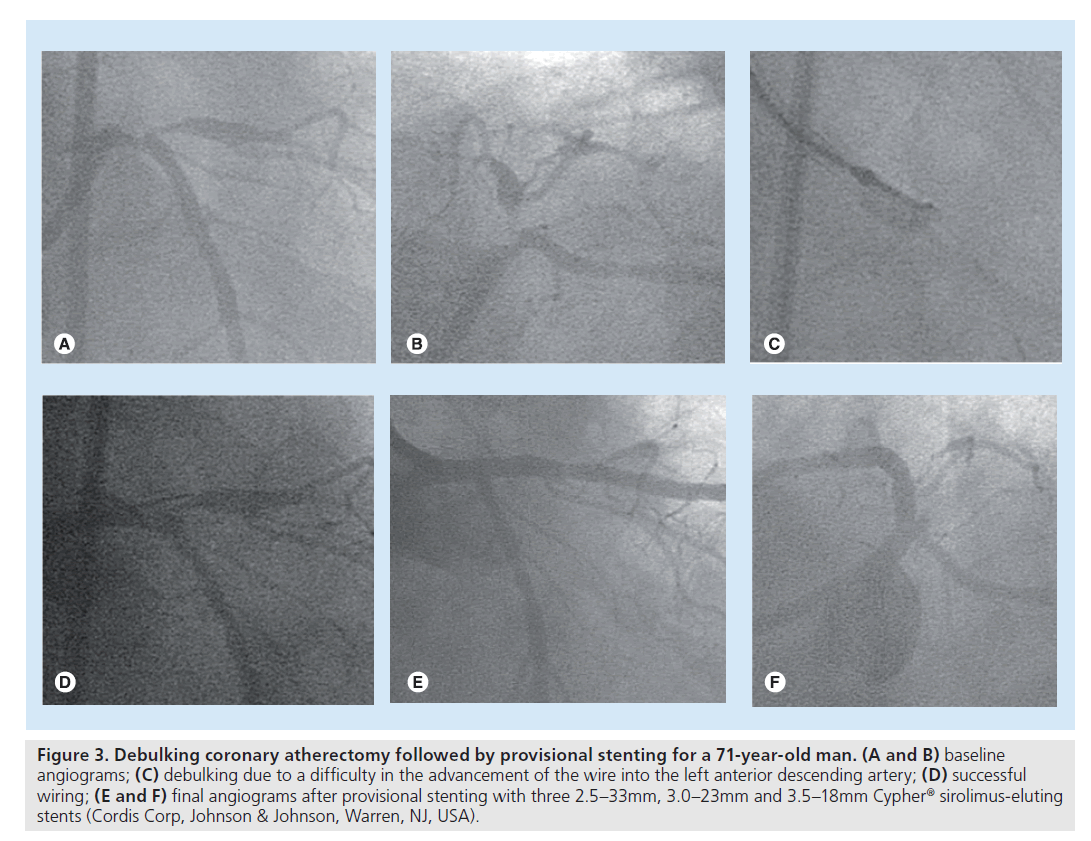

In the BMS era, debulking coronary atherectomy before stenting was widely used in an attempt to reduce restenosis by the removal of plaque burden. However, after the introduction of DES, the role of debulking is more limited due to the dramatic benefit in retenosis reduction. A study suggested a viable role of debulking atherectomy even in the DES era for 99 coronary bifurcations [63]. Of interest, debulking in the main branch and side branch for LMCA stenoses allowed single-stenting in 60 out of the 63 LMCA bifurcation stenoses. Surprisingly, at 1‑year follow-up, no serious adverse event had occurred. This study indicates that debulking may be preferably used in LMCA bifurcations in order to aid a provisional single-stenting strategy. In addition, debulking still plays a limited role in facilitating stent delivery. In a patient illustrated in Figure 3, debulking was used to remove the plaque in the LMCA inhibiting advancement of the wire into the left anterior descending artery. Similarly, rotablator has been used prior to stenting when calcification in the proximal segment prevents stent delivery or the calcified target lesion is not sufficiently dilated. Therefore, although the data are limited, debulking atherectomy or rotablator still has a limited role even in DES treatment to improve lesion compliance.

Figure 3. Debulking coronary atherectomy followed by provisional stenting for a 71-year-old man. (A and B) baseline angiograms; (C) debulking due to a difficulty in the advancement of the wire into the left anterior descending artery; (D) successful wiring; (E and F) final angiograms after provisional stenting with three 2.5–33mm, 3.0–23mm and 3.5–18mm Cypher® sirolimus-eluting stents (Cordis Corp, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA).

▪ Hemodynamic support

Patients in an unstable hemodynamic condition need pharmacological- or device-based hemodynamic support during the procedure for LMCA stenosis. Old age, MI, cardiogenic shock and decreased left ventricular ejection fraction are common clinical conditions requiring elective or provisional hemodynamic support. Among the hemodynamic support devices, which include intraortic balloon pumps, percutanous hemodynamic support devices or left ventricular assist devices, the intraortic balloon pump has most frequently been used. Although there is no doubt that provisional use of an intra-aortic balloon pump in patients with hemodynamic compromise is necessary for a successful procedure, from the literature, the prevalence of planned use of balloon pump varies considerably. A study recently suggested the role of intra-aortic balloon pump support from 219 elective LMCA interventions [64]. They used a prophylactic balloon pump for a broad range of patients with distal LMCA bifurcation lesions, a low ejection fraction of less than 40%, use of debulking devices, unstable angina and critical right coronary artery disease. In that study, interestingly, although the patients receiving elective intra-aortic balloon pump support had a more complex clinical risk profile, the rate of procedural complications was lower than those not receiving its support (1.4 vs 9.3%; p = 0.032). Therefore, at least, its elective use needs to be positively considered for patients with a high-risk condition such as multivessel disease, complex LMCA anatomy, low ejection fraction or unstable presentations. Hopefully, the new support devices, such as Tandem- Heart® (CardiacAssist, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) or the Impella Recover LP 2.5 System (Impella® CardioSystems, Aachen, Germany) may improve the feasibility of implementing these devices and improve complication rates.

▪ Antithrombotics

Although the reported incidence of stent thrombosis in DES treatment for LMCA lesions was very low [19], fear of stent thrombosis remains a major concern preventing more generalized use of DES. Therefore, careful administration of antiplatelet agents is a very important treatment to prevent the occurrence of stent thrombosis. In fact, premature discontinuation of clopidogrel was strongly associated with stent thrombosis in several studies [32,65]. Therefore, as generally recommended, dual antiplatelet therapy including aspirin and clopidogrel (or ticlopidine) should be maintained to 1 year. If the patients appear to be at high risk, a high loading dose (600 mg) or lifelong administration of clopidogrel needs to be considered. A recent study added the benefit of aggressive use of clopidogrel in the early period after DES implantation [66]. After stopping clopidogrel between 31 to 180 days, the risk of cardiac death or MI was 4.20 (p = 0.009) compared with stopping between 181 to 36 days. Furthermore, in some institutions in Asian countries, adjunctive administration of cilostazol has been used for the purpose of reducing thrombotic complications [67].

Aggressive use of antithrombotics should also be considered for complex lesion anatomy or unstable coronary conditions. For example, as shown in previous studies, use of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor may play a role in reducing procedure-related thrombotic complications including death or MI [68]. However, the additive role of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, cilostazol, low-molecular-weight heparin, direct thrombin inhibitors or other new drugs in DES treatment for LMCA lesions needs to be investigated in future studies. Until evidence is accumulated, an aggressive combination of antithrombotic drugs before, during or after the procedure should be considered to avoid thrombotic complications for high-risk patients. Although what constitutes high risk is not well delineated, off-label use of DES, such as diabetes mellitus, multiple stenting, long DES, chronic renal failure, or presentation with MI is a good index of high-risk procedure [69].

Future perspective

Current studies, although limited by nonrandomized study design, small sample size and short-term follow-up, have shown the procedural and mid-term safety and effectiveness of DES to be promising compared with treatment with BMS or CABG. With these attempts, in our opinion, PCI with DES will progressively increase and can be recommended as a reliable alternative to bypass surgery for patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis, especially as the first-line therapy for ostial or shaft stenosis. Although bifurcation stenosis remains challenging for the percutaneous approach, we are still optimistic as further studies on novel procedural techniques, new dedicated stent platforms and optimal pharmacotherapies may improve outcomes. Furthermore, we hope that with the upcoming randomized clinical trials comparing PCI to CABG for unprotected LMCA stenosis, more confidence in the longterm safety, durability and efficacy of PCI will occur in the near future.

Executive summary

stenosis

▪ Comparable incidence compared with bare-metal stent (BMS) treatment.

▪ Requires longer follow-up study.

Risk of stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent treatment

▪ Comparable incidence compared with BMS in current studies.

▪ Reported incidence of less than 2% in elective procedure.

Risk stratification model for prediction of poor prognosis

▪ Good prediction of long-term mortality with EuroSCORE, which is representative of clinical risks.

▪ Long-term prediction with angiographic SYNTAX score.

Repeat revascularization after drug-eluting stent treatment

▪ Very low incidence (<5%) for ostial or shaft left main coronary artery lesions.

▪ Relatively higher risk for left main coronary artery bifurcation lesions.

▪ Lower revascularization rate with use of simple stenting compared with complex stenting, for bifurcation lesions.

Drug-eluting stents compared with bypass surgery

▪ Comparable long-term mortality or myocardial infarction between the two treatments.

▪ Higher or comparable risk of revascularization with use of drug-eluting stents.

Technical considerations

▪ Preference for provisional stenting for left main coronary artery bifurcation lesions with normal left circumflex artery.

▪ Strong recommendation for intravascular ultrasound during stenting.

▪ Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for at least 1 year.

▪ Mechanical support device for hemodynamic instability or complex lesions.

▪ Selective use of debulking atherectomy or rotablator device for lesion preparation.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

- Takaro T, Hultgren HN, Lipton MJ, Detre KM: The VA cooperative randomized study of surgery for coronary arterial occlusive disease II. Subgroup with significant left main lesions. Circulation 54, III107–III117 (1976).

- Chaitman BR, Fisher LD, Bourassa MG et al.: Effect of coronary bypass surgery on survival patterns in subsets of patients with left main coronary artery disease. Report of the Collaborative Study in Coronary Artery Surgery (CASS). Am. J. Cardiol. 48, 765–777 (1981).

- Park SJ, Mintz GS: Left main stem disease. Informa Healthcare, Seoul, Korea (2006).

- Chieffo A, Stankovic G, Bonizzoni E et al.: Early and mid-term results of drug-eluting stent implantation in unprotected left main. Circulation 111, 791–795 (2005).

- Park SJ, Kim YH, Lee BK et al.: Sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis: comparison with bare metal stent implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 351–356 (2005).

- Valgimigli M, van Mieghem CA, Ong AT et al.: Short- and long-term clinical outcome after drug-eluting stent implantation for the percutaneous treatment of left main coronary artery disease: insights from the Rapamycin-Eluting and Taxus Stent Evaluated At Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital registries (RESEARCH and T-SEARCH). Circulation 111, 1383–1389 (2005).

- Chieffo A, Morici N, Maisano F et al.: Percutaneous treatment with drug-eluting stent implantation versus bypass surgery for unprotected left main stenosis: a single-center experience. Circulation 113, 2542–2547 (2006).

- Kim YH, Park SW, Hong MK et al.: Comparison of simple and complex stenting techniques in the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery bifurcation stenosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 97, 1597–1601 (2006).

- Lee MS, Kapoor N, Jamal F et al.: Comparison of coronary artery bypass surgery with percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 864–870 (2006).

- Palmerini T, Marzocchi A, Marrozzini C et al.: Comparison between coronary angioplasty and coronary artery bypass surgery for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis (the Bologna Registry). Am. J. Cardiol. 98, 54–59 (2006).

- Price MJ, Cristea E, Sawhney N et al.: Serial angiographic follow-up of sirolimuseluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery revascularization. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 871–877 (2006).

- Valgimigli M, Malagutti P, Aoki J et al.: Sirolimus-eluting versus paclitaxeleluting stent implantation for the percutaneous treatment of left main coronary artery disease: a combined RESEARCH and T-SEARCH long-term analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 507–514 (2006).

- Valgimigli M, Malagutti P, Rodriguez- Granillo GA et al.: Distal left main coronary disease is a major predictor of outcome in patients undergoing percutaneous intervention in the drug-eluting stent era: an integrated clinical and angiographic analysis based on the Rapamycin-Eluting Stent Evaluated At Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (RESEARCH) and Taxus-Stent Evaluated At Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (T-SEARCH) registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 1530–1537 (2006).

- Chieffo A, Park SJ, Valgimigli M et al.: Favorable long-term outcome after drugeluting stent implantation in nonbifurcation lesions that involve unprotected left main coronary artery. A multicenter registry. Circulation 116, 158–162 (2007).

- n Study suggesting an excellent outcome of nonbifurcation LMCA stenosis intervention with drug-eluting stents. 15 Palmerini T, Barlocco F, Santarelli A et al.: A comparison between coronary artery bypass grafting surgery and drug eluting stent for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery disease in elderly patients (aged >75 years). Eur. Heart J. 28, 2714–2719 (2007).

- Sheiban I, Meliga E, Moretti C et al.: Long-term clinical and angiographic outcomes of treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis with sirolimuseluting stents. Am. J. Cardiol. 100, 431–435 (2007).

- Buszman PE, Kiesz SR, Bochenek A et al.: Acute and late outcomes of unprotected left main stenting in comparison with surgical revascularization. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51, 538–545 (2008).

- Biondi-Zoccai GGL, Lotrionte M, Moretti C et al.: A collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis on 1278 patients undergoing percutaneous drug-eluting stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Am. Heart J. 155, 274–283 (2008).

- Chieffo A, Park S-J, Meliga E et al.: Late and very late stent thrombosis following drug-eluting stent implantation in unprotected left main coronary artery: a multicentre registry. Eur. Heart J. 29(17), 2108–2115 (2008).

- Kim YH, Dangas GD, Solinas E et al.: Effectiveness of drug-eluting stent implantation for patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 101, 801–806 (2008).

- Seung KB, Park DW, Kim YH et al.: Stents versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for left main coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1781–1792 (2008).

- Tamburino C, Di Salvo ME, Capodanno D et al.: Are drug-eluting stents superior to bare-metal stents in patients with unprotected non-bifurcational left main disease? Insights from a multicentre registry. Eur Heart J. 30(10), 1171–1179 (2009).

- Park SJ, Kim YH, Park DW et al.: Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance on long-term mortality in stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Intervent. 2, 167–177 (2009).

- Palmerini T, Sangiorgi D, Marzocchi A et al.: Ostial and midshaft lesions vs. bifurcation lesions in 1111 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis treated with drug-eluting stents: results of the survey from the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. doi :10.1093/eurheartj/ehp223 (2009) (Epub ahead of print).

- Tamburino C, Di Salvo ME, Capodanno D et al.: Comparison of drug-eluting stents and bare-metal stents for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery disease in acute coronary syndromes. Am. J. Cardiol. 103, 187–193 (2009).

- Palmerini T, Marzocchi A, Tamburino C et al.: Two-year clinical outcome with drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in a real-world registry of unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis from the Italian society of invasive cardiology. Am. J. Cardiol. 102, 1463–1468 (2008).

- Kim YH, Park DWD, Lee SW et al.: Long-term safety and effectiveness of unprotected left main coronary stenting with drug-eluting stent compared with bare-metal stent. Circulation 120(5), 400–407 (2009).

- de Lezo JS, Medina A, Pan M et al.: Rapamycin-eluting stents for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary disease. Am. Heart J. 148, 481–485 (2004).

- Meliga E, Garcia-Garcia HM, Valgimigli M et al.: Longest available clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary artery disease: The DELFT (Drug Eluting stent for LeFT main) Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51, 2212–2219 (2008).

- Serruys PW, Morice M-C, Kappetein AP et al.: Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 961–972 (2009).

- Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, Smith PK, Spertus JA: ACCF/SCAI/STS/ AATS/AHA/ASNC 2009 Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization: a report by the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriateness Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology Endorsed by the American Society of Echocardiography, the Heart Failure Society of America, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 53, 530–553 (2009).

- Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E et al.: Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 293, 2126–2130 (2005).

- Lagerqvist B, James SK, Stenestrand U, Lindback J, Nilsson T, Wallentin L: Long-term outcomes with drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in Sweden. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 1009–1019 (2007).

- Spaulding C, Daemen J, Boersma E, Cutlip DE, Serruys PW: A pooled analysis of data comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with bare-metal stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 989–997 (2007).

- Stone GW, Moses JW, Ellis SG et al.: Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxeleluting coronary stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 998–1008 (2007).

- Park D-W, Park S-W, Lee S-W et al.: Frequency of coronary arterial late angiographic stent thrombosis (LAST) in the first six months: outcomes with drug-eluting stents versus bare metal stents. Am. J. Cardiol. 99, 774–778 (2007).

- Farb A, Boam AB: Stent thrombosis redux – the FDA perspective. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 984–987 (2007).

- Arnett EN, Isner JM, Redwood DR et al.: Coronary artery narrowing in coronary heart disease: comparison of cineangiographic and necropsy findings. Ann. Intern. Med. 91, 350–356 (1979).

- Fisher LD, Judkins MP, Lesperance J et al.: Reproducibility of coronary arteriographic reading in the coronary artery surgery study (CASS). Cathet. Cardiovasc. Diagn. 8, 565–575 (1982).

- Isner JM, Kishel J, Kent KM, Ronan JA Jr, Ross AM, Roberts WC: Accuracy of angiographic determination of left main coronary arterial narrowing. Angiographic– histologic correlative analysis in 28 patients. Circulation 63, 1056–1064 (1981).

- Gerber TC, Erbel R, Gorge G, Ge J, Rupprecht H-J, Meyer J: Extent of atherosclerosis and remodeling of the left main coronary artery determined by intravascular ultrasound. Am. J. Cardiol. 73, 666–671 (1994).

- Abizaid AS, Mintz GS, Abizaid A et al.: One-year follow-up after intravascular ultrasound assessment of moderate left main coronary artery disease in patients with ambiguous angiograms. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 34, 707–715 (1999).

- Fassa AA, Wagatsuma K, Higano ST et al.: Intravascular ultrasound-guided treatment for angiographically indeterminate left main coronary artery disease: a long-term follow-up study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 204–211 (2005).

- Jasti V, Ivan E, Yalamanchili V, Wongpraparut N, Leesar MA: Correlations between fractional flow reserve and intravascular ultrasound in patients with an ambiguous left main coronary artery stenosis. Circulation 110, 2831–2836 (2004).

- Pijls NH, Van Gelder B, Van der Voort P et al.: Fractional flow reserve. A useful index to evaluate the influence of an epicardial coronary stenosis on myocardial blood flow. Circulation 92, 3183–3193 (1995).

- Pijls NH, De Bruyne B, Peels K et al.: Measurement of fractional flow reserve to assess the functional severity of coronaryartery stenoses. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 1703–1708 (1996).

- Takagi T, Stankovic G, Finci L et al.: Results and long-term predictors of adverse clinical events after elective percutaneous interventions on unprotected left main coronary artery. Circulation 106, 698–702 (2002).

- Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Byrne RA et al.: Paclitaxel- versus sirolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 53, 1760–1768 (2009).

- Marroquin OC, Selzer F, Mulukutla SR et al.: A comparison of bare-metal and drug-eluting stents for off-label indications. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 342–352 (2008).

- Tu JV, Bowen J, Chiu M et al.: Effectiveness and safety of drug-eluting stents in Ontario. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1393–1402 (2007).

- Tan WA, Tamai H, Park SJ et al.: Long-term clinical outcomes after unprotected left main trunk percutaneous revascularization in 279 patients. Circulation 104, 1609–1614 (2001).

- Kim YH, Ahn JM, Park DW et al.: EuroSCORE as a predictor of death and myocardial infarction after unprotected left main coronary stenting. Am. J. Cardiol. 98, 1567–1570 (2006).

- Valgimigli M, Malagutti P, Rodriguez Granillo GA et al.: Single-vessel versus bifurcation stenting for the treatment of distal left main coronary artery disease in the drug-eluting stenting era. Clinical and angiographic insights into the Rapamycin- Eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (RESEARCH) and Taxus-Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (T-SEARCH) registries. Am. Heart J. 152, 896–902 (2006).

- Colombo A, Moses JW, Morice MC et al.: Randomized study to evaluate sirolimuseluting stents implanted at coronary bifurcation lesions. Circulation 109, 1244–1249 (2004).

- Steigen TK, Maeng M, Wiseth R et al.: Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation 114, 1955–1961 (2006).

- Mintz GS, Nissen SE, Anderson WD et al.: American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Standards for Acquisition, Measurement and Reporting of Intravascular Ultrasound Studies (IVUS). A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 37, 1478–1492 (2001).

- Agostoni P, Valgimigli M, van Mieghem CAG et al.: Comparison of early outcome of percutaneous coronary intervention for unprotected left main coronary artery disease in the drug-eluting stent era with versus without intravascular ultrasonic guidance. Am. J. Cardiol. 95, 644–647 (2005).

- Sonoda S, Morino Y, Ako J et al.: Impact of final stent dimensions on long-term results following sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: serial intravascular ultrasound analysis from the sirius trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 1959–1963 (2004).

- Costa MA, Gigliotti OS, Zenni MM, Gilmore PS, Bass TA: Synergistic use of sirolimus-eluting stents and intravascular ultrasound for the treatment of unprotected left main and vein graft disease. Catheter Cardiovas. Intervent. 61, 368–375 (2004).

- Fujii K, Carlier SG, Mintz GS et al.: Stent underexpansion and residual reference segment stenosis are related to stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. An intravascular ultrasound study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 995–998 (2005).

- Cook S, Wenaweser P, Togni M et al.: Incomplete stent apposition and very late stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation 115, 2426–2434 (2007).

- Okabe T, Mintz GS, Buch AN et al.: Intravascular ultrasound parameters associated with stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent deployment. Am. J. Cardiol. 100, 615–620 (2007).

- Tsuchikane E, Aizawa T, Tamai H, Igarashi Y et al.: The efficacy of pre drug eluting stent debulking by directional atherectomy for bifurcated lesions: a multicenter prospective registry (PERFECT Registry). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49(Suppl. 2), 15B (2007).

- Briguori C, Airoldi F, Chieffo A et al.: Elective versus provisional intraaortic balloon pumping in unprotected left main stenting. Am. Heart J. 152, 565–572 (2006).

- Park DW, Park SW, Park KH et al.: Frequency of and risk factors for stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation during long-term follow-up. Am. J. Cardiol. 98, 352–356 (2006).

- Palmerini T, Marzocchi A, Tamburino C et al.: Temporal pattern of ischemic events in relation to dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 53, 1176–1181 (2009).

- Lee SW, Park SW, Hong MK et al.: Triple versus dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: impact on stent thrombosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46, 1833–1837 (2005).

- Cura FA, Bhatt DL, Lincoff AM et al.: Pronounced benefit of coronary stenting and adjunctive platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition in complex atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation 102, 28–34 (2000).

- Tina L: Pinto Slottow RW: Overview of the 2006 Food and Drug Administration Circulatory System Devices Panel meeting on drug-eluting stent thrombosis. Catheter Cardiovas. Intervent. 69, 1064–1074 (2007).

▪ Landmark study making coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery the standard therapy for unprotected left main coronary artery (LMCA) stenosis.

▪ First study showing the feasibility of drug-eluting stents for unprotected LMCA stenosis.

▪ Study suggesting an excellent outcome of nonbifurcation LMCA stenosis intervention with drug-eluting stents.

▪ First randomized study comparing the outcomes of drug-eluting stents versus CABG.

▪ The largest registry comparing the outcomes of stenting versus CABG for unprotected LMCA stenosis in a nation-based registry.

▪ Study suggesting the hazard of drug-eluting stents compared with bare-metal stents.

▪ Randomized study comparing outcomes of the two current drug-eluting stents.