Short Communication - Clinical Investigation (2019) Volume 9, Issue 1

Prevalence of elevated lipoprotein(a) levels in Korean: A large population-based study

- Corresponding Author:

- Sang Gon Lee

Department of Laboratory Medicine Green Cross Laboratories

Yongin-si Republic of Korea

E-mail: sglee@gclabs.co.kr

Submitted date: 23 February 2019; Accepted: 19 March 2019; Published online: 15 March 2019

Abstract

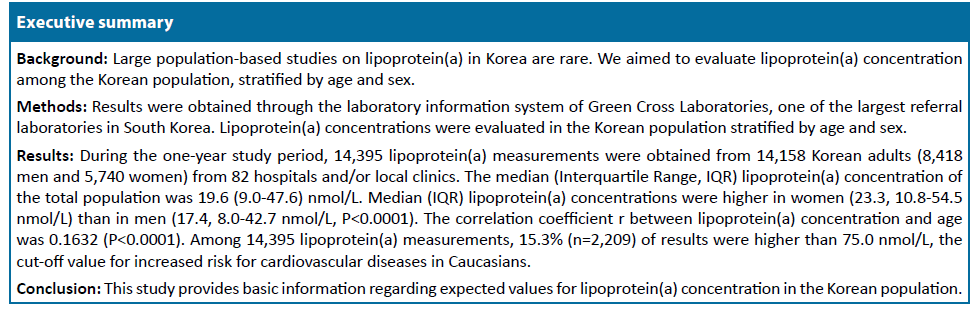

Background: Large population-based studies on lipoprotein(a) in Korea are rare. We aimed to evaluate lipoprotein(a) concentration among the Korean population, stratified by age and sex.

Methods: Results were obtained through the laboratory information system of Green Cross Laboratories, one of the largest referral laboratories in South Korea. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations were evaluated in the Korean population stratified by age and sex.

Results: During the one-year study period, 14,395 lipoprotein(a) measurements were obtained from 14,158 Korean adults (8,418 men and 5,740 women) from 82 hospitals and/or local clinics. The median (Interquartile Range, IQR) lipoprotein(a) concentration of the total population was 19.6 (9.0-47.6) nmol/L. Median (IQR) lipoprotein(a) concentrations were higher in women (23.3, 10.854.5 nmol/L) than in men (17.4, 8.0-42.7 nmol/L, P<0.0001). The correlation coefficient r between lipoprotein(a) concentration and age was 0.1632 (P<0.0001). Among 14,395 lipoprotein(a) measurements, 15.3% (n=2,209) of results were higher than 75.0 nmol/L, the cut-off value for increased risk for cardiovascular diseases in Caucasians.

Conclusions: This study provides basic information regarding expected values for lipoprotein(a) concentration in the Korean population.

Keywords

Lipoprotein(a) Korean • cardiovascular disease • population prevalence • cut-off • lipid

Abbreviations

CHD: Coronary Heart Disease; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; IQR: Interquartile Range; SD: Standard Deviation

Introduction

Lipoprotein(a) is a low-density lipoprotein-like particle in which apolipoprotein B100 is covalently linked to the unique apolipoprotein(a) [1,2]. Elevated plasma concentrations of lipoprotein(a) are a causal risk factor for Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), Coronary Heart Disease (CHD), coronary artery calcification and calcific aortic valve stenosis [3,4]. Lipoprotein(a) has emerged as a potential target to reduce the risk of CVD, and studies have established a causative role for lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic CVD [1-3]. New therapeutics show promise in lowering plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, although the complete mechanisms of lipoprotein(a) lowering are not fully understood [3,5]. Recent therapeutic approaches could help establish the benefit of lowering lipoprotein(a) in a clinical setting for this population [3].

Although lipoprotein(a) levels in the atherothrombotic range are generally accepted as >30 to 50 mg/dL or >75 to 125 nmol/L, researches are still needed for the full understanding of the role of lipoprotein(a) in CVD including the lipoprotein(a) risk cut-offs for CVD to define population risk among different ethnic/racial groups [2]. While some studies on lipoprotein(a) concentrations and their association with various diseases such as CVDs have been conducted in Korean patients, studies using large population-based data are still needed [6-8]. A 10-year prospective cohort study performed in Korea reported that elevated lipoprotein(a) level was an independent predictive risk factor for CVD in type 2 diabetes patients [6].

We aimed to evaluate lipoprotein(a) concentration among the Korean adult population, stratified by age and sex using population-based data. This study has value for predicting the concentration of lipoprotein(a) in Korean adults for use in developing and/or understanding preventive and therapeutic approaches for CVDs based on lipoprotein(a). Furthermore, this study aimed to investigate the association between lipoprotein(a) levels and biomarkers for diabetes including serum or plasma glucose levels and glycosylated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c, HbA1c) [9,10].

Methods

Data for lipoprotein(a) tests conducted from January to December 2017 were obtained from the laboratory information system of Green Cross Laboratories. Green Cross Laboratories is one of the largest referral laboratories in South Korea and provides clinical sample analysis service to nationwide local clinics and hospitals. Lipoprotein(a) results of adults (>18 years) who visited private clinics and underwent lipoprotein(a) tests by Green Cross Laboratories were used for analysis. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations were evaluated in a Korean population stratified by age and sex. All data were anonymized before analysis. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Green Cross Laboratories (GCL-2018-1009-01).

Plasma or serum lipoprotein(a) concentration was determined using a commercial particleenhanced immunoturbidimetric assay using Tinaquant Lipoprotein (a) Gen.2 assay kits (Roche, Germany) with the Roche Modular analytics P (Roche, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This essay presented a reportable range of 7 to 240 nmol/L. Serum glucose concentration was determined using the Glucose HK Gen.3 assay (Roche, Germany), which is based on the hexokinase method using the Roche Cobas 8000 analyzer, c702 module (Roche, Germany). Plasma glucose concentration was determined using the using the Glucose HK Gen.3 assay (Roche, Germany) with the Roche Modular analytics P (Roche, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole blood HbA1c was determined using the Tina-quant Hemoglobin A1c Gen.3 assay (Roche, Germany) with the Roche Cobas c513 (Roche, Germany), which is based on a turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay. Because of limited clinical information, information about fasting status could not be assessed. Patients were classified as laboratory-confirmed diabetes when random glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL according to standards of medical care for diabetes by the American Diabetes Association, 2019 [9,10].

Statistical analysis was executed using MedCalc software for Windows, version 17.9.7 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Lipoprotein(a) was compared among the various age groups. Differences in lipoprotein(a) results and other categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-Square tests, while continuous variables were compared using ANOVA. Nonparametric methods were used for non normally distributed data. A P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

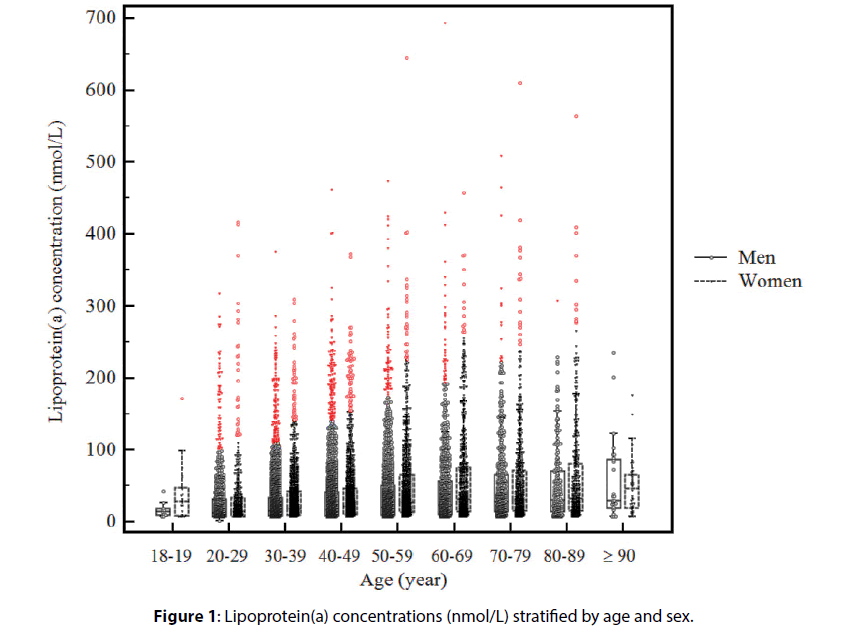

During the one-year study period, 14,395 lipoproteins (a) measurements were obtained from 14,158 Korean patients (8,418 men and 5,740 women) from 82 hospitals and/or local clinics in South Korea. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations stratified by age and sex are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. The median (interquartile range, IQR) age of the population was 46.1 (36.5-59.0) years; median (IQR) lipoprotein(a) concentration was 19.6 (9.0-47.6) nmol/L. Median (IQR) lipoprotein(a) concentrations were higher in women (23.3, 10.8-54.5 nmol/L) than in men (17.4, 8.0-42.7 nmol/L, P<0.0001). The correlation coefficient r between lipoprotein(a) concentration and age was 0.1632 (95% CI 0.1473- 0.1791, P<0.0001). The prevalence of elevated lipoprotein(a) concentration among those at high risk of CVDs is summarized according to different cutoff values in Table 2.

| Men | Women | P-value* | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | N | Median | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | 90th percentile | 95th percentile | N | Median | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | 90th percentile | 95th percentile | |

| 18-19 y | 11 | 13.5 | 9.0 | 17.8 | 32.5 | 41.3 | 22 | 27.8 | 7.3 | 47.1 | 81.3 | 127.6 | 0.1345 |

| 20-29 y | 914 | 11.3 | 7.0 | 30.4 | 65.8 | 114.7 | 462 | 13.3 | 7.0 | 32.7 | 82.2 | 126.8 | 0.0095 |

| 30-39 y | 2271 | 14.4 | 7.3 | 32.9 | 75.7 | 110.5 | 1243 | 18.4 | 9.1 | 42.0 | 79.7 | 126.3 | <0.0001 |

| 40-49 y | 2183 | 16.8 | 7.8 | 41.0 | 87.7 | 147.6 | 1365 | 21.0 | 10.0 | 46.0 | 97.9 | 148.0 | <0.0001 |

| 50-59 y | 1466 | 20.3 | 9.0 | 49.9 | 106.8 | 170.9 | 1048 | 26.7 | 12.6 | 65.7 | 128.4 | 185.9 | <0.0001 |

| 60-69 y | 892 | 23.3 | 9.9 | 55.7 | 115.8 | 182.5 | 695 | 30.9 | 13.8 | 75.3 | 166.0 | 216.3 | <0.0001 |

| 70-79 y | 547 | 27.7 | 13.4 | 65.5 | 138.7 | 178.9 | 583 | 29.9 | 14.5 | 71.4 | 141.1 | 192.7 | 0.1864 |

| 80-89 y | 213 | 29.5 | 13.5 | 70.4 | 126.4 | 160.0 | 410 | 31.5 | 14.5 | 79.9 | 164.4 | 217.8 | 0.2657 |

| = 90 y | 28 | 29.2 | 19.5 | 86.8 | 115.7 | 204.1 | 42 | 46.0 | 19.3 | 65.3 | 90.9 | 128.6 | 0.8478 |

| Total | 8525 | 17.4 | 8.0 | 42.7 | 93.5 | 145.8 | 5870 | 23.3 | 10.8 | 54.5 | 114.5 | 171.7 | <0.0001 |

| *P-values based on ANOVA test for nonparametric data. Abbreviation: y: year |

|||||||||||||

Table 1. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations (nmol/L) stratified by age and sex

| Age (years) | 18-19 | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | 80-89 | = 90 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total subjects, n | 33 | 1376 | 3514 | 3548 | 2514 | 1587 | 1130 | 623 | 70 | 14395 |

| >45 nmol/L, n | 6 | 242 | 714 | 852 | 741 | 560 | 409 | 248 | 31 | 3803 |

| >45 nmol/L, % | 18.2% | 17.6% | 20.3% | 24.0% | 29.5% | 35.3% | 36.2% | 39.8% | 44.3% | 26.4% |

| >75 nmol/L, n | 2 | 136 | 368 | 467 | 461 | 351 | 253 | 155 | 16 | 2209 |

| >75 nmol/L, % | 6.1% | 9.9% | 10.5% | 13.2% | 18.3% | 22.1% | 22.4% | 24.9% | 22.9% | 15.3% |

| >120 nmol/L, n | 1 | 71 | 165 | 242 | 242 | 186 | 140 | 85 | 5 | 1137 |

| >120 nmol/L, % | 3.0% | 5.2% | 4.7% | 6.8% | 9.6% | 11.7% | 12.4% | 13.6% | 7.1% | 7.9% |

| Men, all, n | 11 | 915 | 2271 | 2183 | 1466 | 892 | 547 | 213 | 28 | 8526 |

| >45 nmol/L, n | 0 | 156 | 434 | 500 | 387 | 278 | 190 | 80 | 10 | 2035 |

| > 45 nmol/L, % | 0.0% | 17.0% | 19.1% | 22.9% | 26.4% | 31.2% | 34.7% | 37.6% | 35.7% | 23.9% |

| > 75 nmol/L, n | 0 | 83 | 231 | 275 | 231 | 177 | 115 | 46 | 9 | 1167 |

| >75 nmol/L, % | 0.0% | 9.1% | 10.2% | 12.6% | 15.8% | 19.8% | 21.0% | 21.6% | 32.1% | 13.7% |

| >120 nmol/L, n | 0 | 42 | 96 | 145 | 126 | 82 | 67 | 23 | 3 | 584 |

| >120 nmol/L, % | 0.0% | 4.6% | 4.2% | 6.6% | 8.6% | 9.2% | 12.2% | 10.8% | 10.7% | 6.8% |

| Women, all, n | 22 | 461 | 1243 | 1365 | 1048 | 695 | 583 | 410 | 42 | 5869 |

| > 45 nmol/L, n | 6 | 86 | 280 | 352 | 354 | 282 | 219 | 168 | 21 | 1768 |

| >45 nmol/L, % | 27.3% | 18.7% | 22.5% | 25.8% | 33.8% | 40.6% | 37.6% | 41.0% | 50.0% | 30.1% |

| >75 nmol/L, n | 2 | 53 | 137 | 192 | 230 | 174 | 138 | 109 | 7 | 1042 |

| >75 nmol/L, % | 9.1% | 11.5% | 11.0% | 14.1% | 21.9% | 25.0% | 23.7% | 26.6% | 16.7% | 17.8% |

| >120 nmol/L, n | 1 | 29 | 69 | 97 | 116 | 104 | 73 | 62 | 2 | 553 |

| >120 nmol/L, % | 4.5% | 6.3% | 5.6% | 7.1% | 11.1% | 15.0% | 12.5% | 15.1% | 4.8% | 9.4% |

Table 2. Prevalence of elevated lipoprotein(a) concentration in those at high risk of cardiovascular diseases according to different cut-off values.

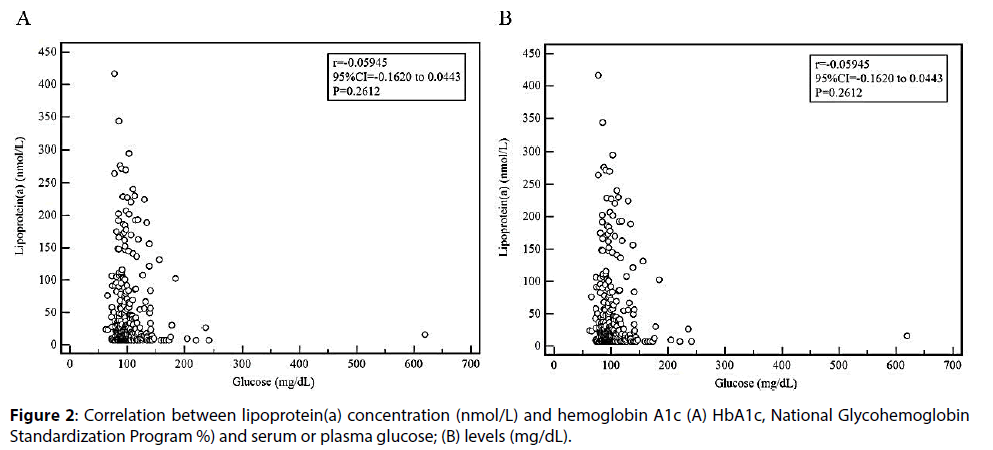

Among 14,395 lipoprotein(a) measurements, 553 (3.8%) measurements had concurrent measurements of serum or plasma glucose (n=360) or whole blood HbA1c (n=211). Among them, only 39 lipoproteins (a) measurements had both serum or plasma glucose and whole blood HbA1c test results. Five patients were classified as diabetes based on a random glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL and 32 patients had HbA1c ≥ 6.5%. The levels of lipoprotein(a) were not significantly associated with serum or plasma glucose levels (Figure 2). HbA1c and glucose concentration were not significantly different among different groups according to different cut-offs for lipoprotein(a) concentration (Table 3).

| HbA1c (NGSP %) | Glucose (mg/dL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipoprotein(a) | N of subjects | Median | IQR | P-value | N of subjects | Median | IQR | P-value |

|  = 45 nmol/L | 141 | 5.6 | 4.8-7.3 | 0.3506 | 29 | 105.0 | 61.6-216.6 | 0.6065 |

|  > 45 nmol/L | 70 | 5.5 | 5.3-5.9 | 9 | 110.0 | 97.5-144.0 | ||

|  = 75 nmol/L | 166 | 5.6 | 5.3-6.0 | 0.4531 | 30 | 104.5 | 88.0-119.0 | 0.4963 |

|  > 75 nmol/L | 45 | 5.6 | 5.4-6.0 | 8 | 124.0 | 92.0-148.0 | ||

|  = 120 nmol/L | 188 | 5.6 | 5.3-6.0 | 0.4530 | 33 | 105.0 | 87.3-126.8 | 0.8291 |

|  > 120 nmol/L | 23 | 5.6 | 5.3-6.0 | 5 | 110.0 | 96.5-142.0 | ||

| Abbreviation: IQR: Interquartile Range; NGSP: National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program | ||||||||

Table 3. Hemoglobin A1c and glucose concentration according to different cut-offs for lipoprotein(a) concentration.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated serum and plasma lipoprotein(a) results in Korean adults in 2017. This is a large population-based study in a Korean population and provides the expected values for lipoprotein(a) in Korean adults.

The cut-offs for what is considered lipoprotein(a)- driven risk, and the effects of approved and emerging therapies varies greatly among studies, ranging from 20 mg/dL to 60 mg/dL (48 nmol/L to 144 nmol/L with a conversion factor of nmol/L × 0.4167=mg/ dL) [2,4,11-13]. A lipoprotein(a) concentration of 30 mg/dL (72 nmol/L), which approximate the 75th percentile in white populations is widely used as a cut‑off point or threshold value in Canada and the United States [2,12-15]. This value The European Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society recommends screening for elevated lipoprotein(a) in those at intermediate or high CVD/CHD risk and defines a desirable lipoprotein(a) level ≤ 50 mg/dL (120 nmol/L) [16]. They also suggest that the risk of lipoprotein(a) is significant when levels are >80th percentile [2,17]. Although some publications have described lipoprotein(a) concentrations in South Korea, a large-population-based study has not been conducted. In a previous study performed in 2,611 Korean adults (92% of subjects were men) who underwent repeated medical checkups at one health promotion center with coronary artery calcium score for coronary artery calcification measurement [18] within one year of 2014, the mean (SD) value of lipoprotein(a) was 71.3 (66.7) nmol/L using a highsensitivity immunoturbidimetric assay of the Roche modular P800 analytical module system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) [4]. In that study, subjects with lipoprotein(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL (120 nmol/L) had high odds ratio for coronary artery calcification progression compared to those with lipoprotein(a) <50 mg/dL (120 nmol/L) after adjusting for confounding factors; 15.6% of subjects had lipoprotein(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL (120 nmol/L) in that study [4].

In this study, the 75th percentile value of lipoprotein(a) was 47.6 nmol/L, which was comparable with previous studies performed in New Zealand, using the 75th percentile value as the cut-off for risk of vascular diseases (45 nmol/L) [11]. Among 14,395 lipoprotein(a) measurements in this study, 15.3% (n=2,209) of results were higher than 75.0 nmol/L, and 7.9% (n=1,137) of results were higher than 120.0 nmol/L. It is well known that the prevalence of elevated lipoprotein(a) is highly variable and ethnicity-specific [2,19]. A recent study performed by the NHLBI Working Group reported that the global prevalence of elevated lipoprotein(a) levels >120 nmol/L was 30% in Africa, 25% in South Asia, 20% in Northern America, Europe and Oceania, 15% in Latin America, and 10% in Asia [2]. In this study, 7.9% (1,137/14,395) of lipoprotein(a) results were ≥ 120 nmol/L, which was comparable with previous studies [2,11]. However, for clinical risk prediction, it remains unknown whether absolute cut-offs, risk percentiles, or race-specific thresholds better identify high-risk individuals [2]. Future studies including the relationship between genetic polymorphisms, apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and lipoprotein(a) levels with major adverse cardiovascular events in different ethnic groups will be needed [19].

In this study, lipoprotein(a) concentrations were higher in women (23.3, 10.8-54.5 nmol/L) than in men (17.4, 8.0-42.7 nmol/L, P<0.0001), which was comparable to the Framingham Heart Study, with 90th percentile lipoprotein(a) levels of 39 mg/dL in men and 39.5 mg/dL in women (units of mass) [20,21]. Lipoprotein(a) levels by sex in different ethnic populations, the significance of lipoprotein(a) levels associated with vascular diseases, and the relationship with disease associations and treatment outcomes between sexes and among different ethnic groups have been inconsistently reported among different studies [21]. Future studies are needed to determine the role lipoprotein(a) reduction may have on the burden of vascular diseases in various ethnicities [3,21].

In this study, lipoprotein(a) levels were not significantly associated with serum or plasma glucose and HbA1c levels. Because only small numbers of lipoprotein(a) measurements had concurrent HbA1c or glucose measurements, this might have affected statistical outcomes. The association between lipoprotein(a) and serum biomarkers of diabetes and CVD should be considered and validated with further studies.

The limitation of this study was the lack of clinical information including detailed documentation of concurrent medical conditions such as diabetes and medication histories, physical examination, and other laboratory measures associated with CVD/CHD and disease severity. Recent studies reported that stress activation could trigger various CVDs [22-24] and elevated lipoprotein enhanced stress levels [25,26]. Future studies are needed to clarify the potential impact of elevated lipoprotein in stress activation which contributes to CVD. However, the populationbased data of this study have value for calculating expected lipoprotein(a) concentrations in Korean adults for use in developing and/or understanding preventive and therapeutic approaches for CVD/ CHD based on lipoprotein(a).

In conclusion, this study provides basic information regarding expected lipoprotein(a) concentrations in Korean adults. Future studies on lipoprotein(a) values and their association with clinical findings are needed. The population-based data of this study have value for predicting the concentration of lipoprotein(a) in Korean adults for use in developing and/or understanding preventive and therapeutic approaches for CVDs based on lipoprotein(a).

Acknowledgment

We thank Ms. Son and Mr. Kim at Green Cross Laboratories for their support to document arrangement.

Contributors

Study concept and design: RC and SGL. Acquisition and preparation of the data set: RC, YO, SL, and SHK. Statistical analyses: RC. Interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript: RC. Writingreview and editing: RC, MJP, SGL, and EHL. SGL had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and agreed on the final manuscript as well as the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

None

Competing Interests

None declared

Patient Consent

Detail has been removed from these case descriptions to ensure anonymity.

Ethics Approval

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Green Cross Laboratories (GCL-2018-1009-01).

Provenance and Peer Review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- Lippi G, Franchini M, Targher G. Screening and therapeutic management of lipoprotein(a) excess: review of the epidemiological evidence, guidelines and recommendations. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry 2011;412:797-801.

- Tsimikas S, Fazio S, Ferdinand KC, et al. NHLBI Working Group Recommendations to Reduce Lipoprotein(a)-Mediated Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Aortic Stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;71:177-92.

- Scipione CA, Koschinsky ML, Boffa MB. Lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice: New perspectives from basic and translational science. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences 2018;55:33-54.

- Cho JH, Lee DY, Lee ES, et al. Increased risk of coronary artery calcification progression in subjects with high baseline Lp(a) levels: The Kangbuk Samsung Health Study. International journal of cardiology 2016;222:233-7.

- van Capelleveen JC, van der Valk FM, Stroes ES. Current therapies for lowering lipoprotein (a). Journal of lipid research 2016;57:1612-8.

- Lim TS, Yun JS, Cha SA, et al. Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels predict cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 10-year prospective cohort study. The Korean journal of internal medicine 2016;31:1110-9.

- Ko SH, Song KH, Ahn YB, et al. The effect of rosiglitazone on serum lipoprotein(a) levels in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 2003;52:731-4.

- Pare G, Caku A, McQueen M, et al. Lipoprotein(a) Levels and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction Among Seven Ethnic Groups. Circulation 2019.

- Summary of Revisions: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes care 2019;42:S4-s6.

- 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes care 2019;42:S13-s28.

- Jones GT, van Rij AM, Cole J, et al. Plasma lipoprotein(a) indicates risk for 4 distinct forms of vascular disease. Clinical chemistry 2007;53:679-85.

- Marcovina SM, Koschinsky ML. A critical evaluation of the role of Lp(a) in cardiovascular disease: can Lp(a) be useful in risk assessment? Seminars in vascular medicine 2002;2:335-44.

- Tsimikas S. A Test in Context: Lipoprotein(a): Diagnosis, Prognosis, Controversies, and Emerging Therapies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017;69:692-711.

- Shai I, Rimm EB, Hankinson SE, et al. Lipoprotein (a) and coronary heart disease among women: beyond a cholesterol carrier? European heart journal 2005;26:1633-9.

- Stefanutti C, Julius U, Watts GF, et al. Toward an international consensus-Integrating lipoprotein apheresis and new lipid-lowering drugs. Journal of clinical lipidology 2017;11:858-71.e3.

- Rubenfire M, Vodnala D, Krishnan SM, et al. Lipoprotein (a): perspectives from a lipid-referral program. Journal of clinical lipidology 2012;6:66-73.

- Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. European heart journal 2016;37:2999-3058.

- Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. The New England journal of medicine 2008;358:1336-45.

- Lee SR, Prasad A, Choi YS, et al. LPA Gene, Ethnicity, and Cardiovascular Events. Circulation 2017;135:251-63.

- Bostom AG, Gagnon DR, Cupples LA, et al. A prospective investigation of elevated lipoprotein (a) detected by electrophoresis and cardiovascular disease in women. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1994;90:1688-95.

- Forbang NI, Criqui MH, Allison MA, et al. Sex and ethnic differences in the associations between lipoprotein(a) and peripheral arterial disease in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Journal of vascular surgery 2016;63:453-8.

- Yan J, Thomson JK, Zhao W, et al. Role of Stress Kinase JNK in Binge Alcohol-Evoked Atrial Arrhythmia. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;71:1459-70.

- Gao X, Wu X, Yan J, et al. Transcriptional regulation of stress kinase JNK2 in pro-arrhythmic CaMKIIdelta expression in the aged atrium. Cardiovascular research 2018;114:737-46.

- Yan J, Zhao W, Thomson JK, et al. Stress Signaling JNK2 Crosstalk With CaMKII Underlies Enhanced Atrial Arrhythmogenesis. Circulation research 2018;122:821-35.

- Chen X, Yu W, Li W, et al. An anti-inflammatory chalcone derivative prevents heart and kidney from hyperlipidemia-induced injuries by attenuating inflammation. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2018;338:43-53.

- Tie G, Yan J, Messina JA, et al. Inhibition of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Enhances the Apoptosis Induced by Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein in Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Journal of vascular research 2015;52:361-71.