Review Article - Interventional Cardiology (2015) Volume 7, Issue 2

Sex differences in clinical outcomes following coronary revascularization

- Corresponding Author:

- Duk-Woo Park

Division of Cardiology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine

388-1 Poongnap-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul, 138–736, Korea

Tel: +82 2 3010 3995

Fax: +82 2 487 5918

E-mail: dwpark@amc.seoul.kr

Abstract

There have been several reports suggesting that the response to treatment for patients with significant coronary heart disease was not equal among males and females. Most of the early investigations on sex differences after surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization suggested worse clinical outcomes in females compared with male counterparts. However, along with the advent of new revascularization techniques and devices, recent trials have shown somewhat narrowed sex-based differences in cardiovascular outcomes. Given that sex-based difference in outcomes and prognosis is still an important ongoing issue, this article systematically reviewed the cumulative evidence from key clinical studies and tried to help guide the physician in making sex-specific treatment decisions for patients with significant coronary heart disease requiring coronary revascularization.

Keywords

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery, coronary heart disease, gender, mortality, percutaneous coronary intervention

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) accounts for more than half of cardiovascular deaths in both the males and the females [1]. However, there were numerous sex-based differences in IHD in terms of prevalence, clinical symptoms, diagnostic accuracy, response to treatment and prognosis. Whether these sexspecific differences were directly attributable to true sex-related biologic difference or were caused by the disparities in sociocultural experiences and the prevalence of concomitant risk factors has been debated for decades. Notwithstanding these unclear understandings, treating physicians have believed that diverse treatment modalities in everyday practice might yield comparable efficacy and safety in both males and females, which might not be true.

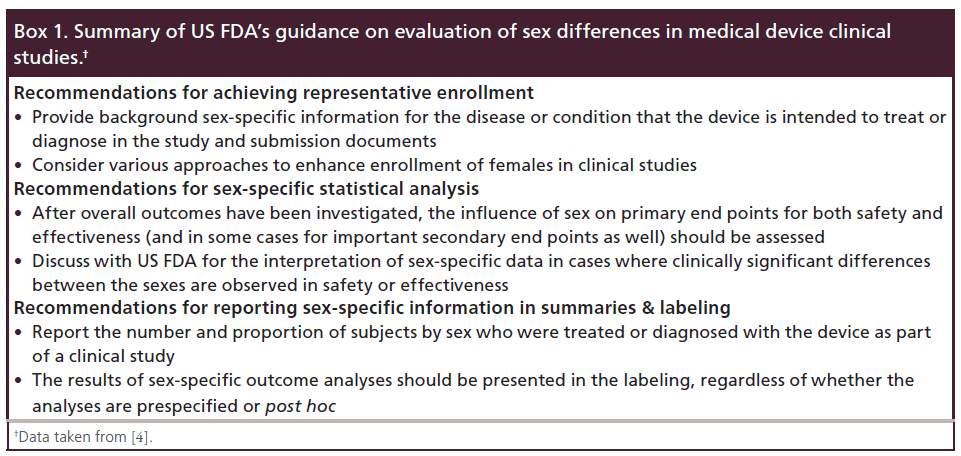

Clinical evidence regarding treatment and prognosis of various clinical subsets of coronary heart disease (CHD) were largely based on male patients, since females have been under-represented in clinical research trials [2]. And, up to recently, many important studies still are not designed to specifically examine sex-specific differences from the beginning, thus making it difficult to evaluate whether study findings are equally applicable to female as well as male patients. To overcome this ‘sex gap’ representation, the US NIH instructed to include both males and females in clinical studies and when studied health condition affects both sexes, to analyze data by sex [3]. Moreover, the US FDA recently issued draft guidance on the study and evaluation of sex differences in implantable medical device clinical studies (Box 1) [4].

During the last two decades, there has been a revolutionary change in the field of surgical or percutaneous revascularization treatments for significant CHD. New methods that minimize the invasiveness and risks involved with coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery have been developed, and rapid advancements of novel techniques, devices and adjunctive pharmacotherapies led percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to extend its clinical application for more complex subsets of patients. In this review, we investigated the cumulative evidence regarding sex-specific differences of clinical outcomes among patients with significant CHD requiring surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization based on published literatures.

Mechanisms leading to differential sex-specific outcomes in CHD

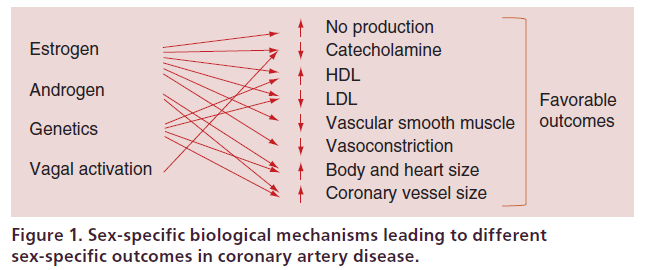

As illustrated in Figure 1, multiple biological factors contribute to the different outcomes of CHD between females and males. The most obvious biological factor is hormonal difference such that estrogen affords females a protective advantage against CHD before menopause. Female sex hormone, precisely 17 betaestradiol, modulates cholesterol levels, stimulates nitric oxide and prevents vessel contraction by acting with endothelial and vascular smooth muscle factors [5]. Difference in autonomic responses has also been postulated as a putative mechanism to account for sex-specific outcomes in CHD since vagal activation is more common in females than in males during acute coronary events and this may contribute to antiarrhythmic effects or reduction of ischemic myocardial burden [6]. Difference in coronary vessel caliber might also seem to play a role. Coronary arteries are smaller in females than males independent of body size, and along with different body habitus and smaller heart size, these structural factors may lead to technical difficulties, greater risk of incomplete revascularization and higher rates of restenosis in female patients undergoing either PCI or CABG surgery [7,8].

Figure 1. Sex-specific biological mechanisms leading to different sex-specific outcomes in coronary artery disease.

Disparities in the prevalence of risk factors and sociocultural issues, which are frequently proposed in abundant clinical studies, seem to be more plausible explanation leading to different sex-based outcomes. Females are usually older when presenting with CHD, and more likely to have greater risk factor burden or comorbid conditions and more functional disability compared with male counterparts [9]. Furthermore, there are evidences that physician bias and difference in patient behaviors contribute to different referral patterns for noninvasive testing or coronary angiography [10,11]. These biological and nonbiological factors might function independently or synergistically to the sex-specific difference in CHD outcomes.

Sex-specific differences in prevalence, patterns & outcomes of CHD

In general, the prevalence of all forms of CHD (i.e., stable angina or acute coronary syndrome [ACS]) was higher in males than females within each age stratum over 20 years of age, and this finding contributes to the common perception that heart disease is a man’s disease [1,12]. However, it is well known that lifetime development of CHD in males and females differ. Some population-based studies, including the INTERHEART study, demonstrated that the first presentation with CHD occurs approximately 8–10 years later among females than males [13]. Although an exact mechanism is still incompletely understood, this later onset of disease in females is speculated to be the output of hormonal protection from early development of atherosclerosis; since the incidence of CHD sharply increases after menopause and by the age of 70, females have more incidence of CHD as males do.

Sex differences in patterns of CHD presentation were also suggested. Prior studies of elderly patient cohorts indicated that females were more likely to present with atypical forms of chest pain compared with males [14]. This tendency was also consistent even in younger patients with ACS; two recent studies demonstrated that females were more likely to present without chest pain compared with males [15,16]. In addition to the sex differences in diagnostic sensitivity of noninvasive stress tests and ECG [10,17], these disparities in symptom profile might contribute to the delay in seeking medical care as well as the under or misdiagnosis of acute form of CHD, probably affecting the outcome [18,19].

There have been several reports showing sex-specific outcomes of CHD according to different clinical settings such as stable angina or ACS (Table 1). In general, many registries and population-based studies suggested that female patients with CHD might have higher rates of classic risk factors such as hypertension or diabetes, and have lower probability to receive appropriate medical therapy or coronary revascularization compared with male patients [1,11,20–21]. However, this difference of risk-factor profiles did not seem to always translate into poor outcomes with women. Data from the national registers in Finland and Euro Heart Survey described higher mortality for female patients with stable angina at 1–4 years of follow-up [11,21]. But, recent results from the international CLARIFY registry including 30,977 patients with stable CHD demonstrated similar 1-year rate of the composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke for men and women [22].

| Study (year) | Patients (n) | Characteristics | Clinical setting | Main findings (female vs male) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro Heart | 3779 | Europe, 196 centers, | Stable | 1-year death, MI: 3.7 vs 2.9%; adjusted | [14] |

| Survey (2006) | prospective registry | angina | HR: 2.09 (1.14, 3.85); p = 0.02 | ||

| CLARIFY | 30,977 | International, 45 | Stable | 1-year CV death, MI, stroke: 1.8 vs | [22] |

| registry (2012) | countries, prospective | angina | 1.7%; adjusted HR: 0.93 (0.75, 1.15); | ||

| registry | p = 0.5 | ||||

| 1-year death: 1.6 vs 1.5%; adjusted | |||||

| HR: 0.91 (0.72, 1.13); p = 0.39 | |||||

| NRMI 2 (1999) | 384,878 | USA, 1658 centers, | AMI | Hospital death: aged <50 years; 6.1 vs | [23] |

| prospective cohort | 2.9%; aged 75–79 years; 19.1 vs 18.4% | ||||

| USIC registry | 4347 | France, nationwide | AMI | Hospital death: 16 vs 9%; younger | [24] |

| (2006) | registry | group, adjusted OR: 2.4 (1.4, 4.3); | |||

| p = 0.003; older group; adjusted | |||||

| OR: 1.2 (0.9, 1.7); p = 0.3 | |||||

| 1-year death: 25 vs 16%; younger | |||||

| group: 14 vs 8%, p = 0.0005; older | |||||

| group: 29 vs 27%, p = 0.31 | |||||

| Berger et al. | 136,247 | International, pooled | ACS | 30-day death: STEMI, 12.3 vs 5.8%, | [25] |

| (2009) | data from 11 RCTs | adjusted OR: 1.15 (1.06,1.24); NSTEMI, | |||

| 6.4 vs 4.3%, adjusted OR: 0.77 (0.63, | |||||

| 0.95); unstable angina, 2.4 vs 2.8%; | |||||

| adjusted OR: 0.55 (0.43, 0.70) | |||||

| NRMI (2009) | 361,429 | USA, 1057 centers, | AMI | Hospital death: STEMI, unadjusted | [26] |

| retrospective cohort | RR: 1.64 (1.59, 1.69); NSTEMI, | ||||

| unadjusted RR: 1.22 (1.09, 1.15) | |||||

Table 1. Current evidences for sex-specific differences in outcomes of coronary heart disease.

Among ACS patients, sex differences in mortality seem to depend largely on age. Based on US National Registry of Myocardial Infarction and several other studies, younger females (aged <50–55 years) showed a mortality excess compared with aged men presenting with acute MI, whereas significant mortality differences were not found in older population [23–24,27–28]. Although the reason was not fully understood, disproportionate burden of coronary risk factors and comor-bidities in younger females seemed to account for this age-dependent disparity in mortality among patients presented with acute MI. The mortality gap was also observed by the type of ACS [25]. In this study, among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 30-day mortality was higher among females compared with males, whereas in non-STEMI (NSTEMI) and unstable angina, mortality was lower among females. Similarly, the US National Registry of Myocardial Infarction data from 2000 and 2006 showed higher hospital mortality among females in the STEMI population than NSTEMI population [26]. To date, there was also a considerable debate regarding the evidence for the sex difference in long-term outcomes [2], but of note, survival for both the male and female patients after treatment for acute myocardial infarction have improved markedly over decades, suggesting that evidence-based therapies might have equal clinical benefit for both genders [27,29].

Sex-specific outcomes following CABG

Key findings of studies regarding short- and longterm mortality for patients who underwent CABG are summarized in Table 2. Most of early investigations on sex-based differences related to CABG consistently showed that females had considerably higher in-hospital mortality and morbidity than males [30–32]. In accordance with the general CHD population, there were major sex differences in the preoperative risk-factor profiles and surgical factors among patients referred for CABG [30–34]. However, there have been conflicting reports whether this difference in outcomes persists after adjustment for all identifiable risk factors and thus, many investigators still argue that female sex is an independent predictor of poor perioperative outcome [34–38]. Up to date, two meta-analyses exist within this context. Nalysnyk et al. [39] suggested that female sex was associated with an increased risk for death (unadjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.48–2.48) after CABG. Consistently, in the more recent contemporary meta-analysis by Takagi et al. [35], there was a significant increase in short-term mortality in females compared with male patients (adjusted OR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.29–1.49; p < 0.001). As a result, several risk models such as EuroSCORE and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score, which were developed to predict operative mortality, included female sex as a negative prognostic factor [40,41]. Despite these relatively unfavorable early outcomes in females compared with males, once past the perioperative time period, longterm survival for females appeared to be comparable to or even slightly better than for males [42–45].

| Study | Characteristics | n | Main findings (female vs male) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blankstein | Isolated CABG, USA, 31 | 5023 females and | Operative mortality: | [37] |

| et al. | hospitals, 1999–2000 | 10,417 males | 4.24 vs 2.23%; risk adjusted | |

| mortality: 3.81 vs 2.43% | ||||

| CCORP | Isolated CABG, USA, 121 | 10,708 females and | Operative mortality: 4.60 vs | [38] |

| database | hospitals, 2003–2004 | 29,669 males | 2.53%; adjusted OR: 1.61 | |

| (1.40, 1.84) | ||||

| ASCTS cardiac | Isolated CABG, Australia, | 4780 females and | In-hospital mortality: 2.3 vs 1.6%, | [44] |

| surgery | 18 hospitals, 2001–2009 | 16,754 males | 30-day mortality: 2.2 vs 1.4%, | |

| database | 7-years survival: 82.8 vs 84.1% | |||

| Ahmed et al. | Isolated CABG, Australia, | 1114 females and | 7.9-year mortality: adjusted | [45] |

| single center, 1996–2004 | 3628 males | HR: 0.92 (0.77, 1.11); p = 0.38 | ||

| CCN database | Isolated CABG, Canada, | 14,393 females and | 11-year mortality: adjusted HR: 0.9 | [43] |

| population-based cohort, | 51,800 males | (0.83, 0.98); p < 0.01 | ||

| 1991–2002 | ||||

| BAR | Isolated CABG, USA | 489 females and | 5.4-year mortality: 12.8 vs 12.0%; | [42] |

| and Canada, 18 centers, | 1340 males | adjusted RR: 0.60 (0.43, 0.84); | ||

| 1988–1991 | p = 0.003 |

Table 2. Summary of studies regarding sex-specific outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting surgery.

Underutilization of internal thoracic artery (ITA) in female is one of the major concerns, which has been postulated to explain the different outcomes between both sexes after CABG [34,46]. In contrast with the vein conduits, ITA appears to be virtually resistant to the development of intimal hyperplasia and atherosclerosis combined with intact functional capacity, such as endothelial-dependent vasodilation, after grafting [47]. These unique characteristics led ITA graft to have excellent 5- and 10-year patency rates and compared with CABG using only venous grafts, the use of at least one ITA is associated with improved short- and longterm survival rates [48–50]. Although the benefits of ITA graft over the saphenous vein graft are not in dispute, a contemporary observational study based on the STS National Cardiac Database including 541,368 patients reported profound underutilization of ITA (OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.61–0.63; p < 0.001) in female than male patients [46]. The efforts to eliminate these disparities can be indirectly emphasized based on some reports in that short- and long-term survival rates were not different when ITA was equally used in both sexes [51,52]. In the same context, the use of bilateral ITA was also reported to be less frequent in females compared with males based on several studies [46,53]. This difference is a potential future issue since there are growing burden of published studies showing better long-term survival in patients receiving bilateral ITA compared with single ITA grafting [53–56].

Off-pump CABG (OPCAB), compared with the conventional on-pump CABG, is a less-invasive established technique and has been introduced to eliminate overall operative mortality and morbidity attributable to cardiopulmonary bypass. While this technique was expected to provide some benefits in end-organ function during operation, some technical limitation can result in poor graft quality and incomplete revascularization [57]. Several clinical trials comparing OPCAB with on-pump CABG have failed to demonstrate a difference in long-term clinical outcomes [58–60]. However, at least for the early outcomes, there are some promising results for females after OPCAB compared with on-pump CABG [61–64]. Two studies using Healthcare Company database compared on-pump CABG and OPCAB in 16,871 and 21,902 consecutive females and demonstrated 42% (adjusted OR: 1.42) and 73.3% (adjusted OR: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.22–2.46; p = 0.002) higher mortality rate in patients undergoing on-pump CABG, respectively [62,63]. Another recent study by Puskas et al. showed that OPCAB was associated with a significant reduction in death (riskadjusted OR: 0.39; p = 0.001) in females [61]. Despite these favorable evidences suggesting that OPCAB might be better than on-pump CABG for females, further well-designed studies are needed to define the impact of OPCAB in females, since most current evidences are based on retrospective observational studies.

Sex-specific outcomes following PCI

Sex-specific outcomes after PCI have changed over time along with the advent of the procedural techniques and coronary stent system. Before the introduction of drug-eluting stent (DES), PCI was performed either by conventional balloon angioplasty or implantation of bare-metal stent (BMS). Most of early registries in the balloon angioplasty era found that female patients had lower rates of angiographic success, two- to threefold higher in-hospital mortality, and worse long-term clinical outcomes compared with male patients [65–67]. Subsequent studies in the BMS era indicated that the outcomes after PCI significantly improved in females and sex-based differences in outcomes have much narrowed [65,68–71].

DESs are currently used in preference to BMS in most cases because they are associated with marked reductions in restenosis and repeat revascularization. Several clinical trials and registries suggested a consistent beneficial effect of DES over BMS equally in both female and male patients [72–75]. A recent analysis from US National Cardiovascular Data Registry CathPCI Registry found that, compared with BMS, DES use was associated with lower long-term likelihood for death (female: adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.76–0.81; male: HR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.74–0.79) and MI (female: adjusted HR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.74–0.84; male: HR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.77–0.85) equally in both sexes. Thus, the sex gap in clinical outcomes after PCI appears to significantly decrease with the use of DESs. Currently, there are limited published data focusing on sex-specific outcomes after PCI predominantly using DESs. The long-term sex-specific outcomes of DEStreated patients from recent important studies were summarized in Table 3. Overall, female revealed to have comparable benefits to male from PCI with DES on long-term outcomes. Whether newer-generation DES further benefits in females over early-generation DESs remains to be determined. A recent large-scale analysis of DES-treated females provided a clue for this issue. Stefanini et al. pooled data for female participants from 26 randomized trials of DES and analyzed 3-year follow-up outcomes according to the stent type [76]. They found that newer-generation DES was associated with significantly lower rates of death or MI (9.2 vs 10.9%; p = 0.01), definite or probable stent thrombosis (1.1 vs 2.1%; p = 0.03) and target lesion revascularization (6.3 vs 7.8%; p = 0.005) than was the use of early-generation DES in females. As discussed above, the reduction of sex-based differences in outcome after PCI was evident over time, even after rigorous adjustment of these clinical risk profiles. This suggests that improved interventional techniques and devices may have predominantly played a role in the improvement of outcomes in females.

| Study | Characteristics | Patients (n) | Main findings (female vs male) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mikhail et al. | PES, pooled analysis of | 665 females and | 5-year mortality: 2.08 vs 1.90%; | [72] |

| five RCTs | 1606 males | p = 0.54; adjusted HR: 0.83 (0.60, 1.14) | ||

| 5-year MI: 1.86 vs 1.60%; p = 0.42; | ||||

| adjusted HR: 1.12 (0.80, 1.58) | ||||

| Stefanini et al. | SES/PES/ZES, pooled | 1164 females | 2-year cardiac mortality: 2.9 vs 2.5%; | [77] |

| analysis of three RCTs | and 3721 males | p = 0.43; adjusted OR: 1.04 (0.61, 1.80); | ||

| p = 0.87 | ||||

| 2-year MI: 5.8 vs 4.7%; p = 0.13; | ||||

| adjusted HR: 1.07 (0.75, 1.53); p = 0.71 | ||||

| Abbott et al. | SES/PES, NHLBI registry | 486 females and | 1-year mortality: 3.8 vs 3.6%; p = 0.97; | [75] |

| 974 males | adjusted RR: 1.02 (0.54, 1.93); p = 0.95 | |||

| 1-year MI: 4.4 vs 4.5%; p = 0.94, | ||||

| adjusted RR: 1.07 (0.61, 1.89); p = 0.81 | ||||

| Onuma et al. | SES/PES, pooled analysis | 798 females and | 3-year mortality: 10.2 vs 9.5%; p = 0.52; | [74] |

| of two registries | 2007 males | adjusted HR: 0.92 (0.68, 1.25) | ||

| 3-year MI: 4.6 vs 4.4%; p = 0.96; | ||||

| adjusted HR: 1.22 (0.79, 1.87) | ||||

| Anderson et al. | SES/PES/EES/ZES, US | 134,679 | 2.5-year mortality: 16.3 vs 15.8%; | [73] |

| NCDR CathPCI registry | females and | p = 0.002; adjusted HR: 0.92 (0.90, 0.94) | ||

| 180,283 males | 2.5-year MI: 7.8 vs 7.6%; p = 0.868; | |||

| adjusted HR: 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | ||||

| Park et al. | SES/PES/EES/ZES, pooled | 7180 females | 2.1-year cardiac mortality: 1.4 vs 1.3%; | [78] |

| analysis of eight RCTs | and 16,424 | adjusted HR: 1.05 (0.93,1.19); p = 0.41 | ||

| and three observational | males | 2.1-year MI: 9.6 vs 7.5%; adjusted | ||

| studies | HR: 1.27 (1.16, 1.39); p < 0.001 | |||

Table 3. Summary of landmark studies regarding long-term sex-specific outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention using drug-eluting stents.

Executive summary

Current problems in conducting clinical trials for evaluation of sex-based differences in patients with coronary heart disease

• Females are under-represented in clinical research trials as well as cardiovascular device trials.

• Many studies are not designed to specifically examine sex-specific difference.

Mechanisms leading to different responses in females compared with males

• Biological factors include differences in sex hormone, autonomic responses and size of heart or coronary vessels.

• Nonbiological factors include differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and sociocultural experiences.

Sex-specific differences in prevalence, patterns & outcomes of coronary heart disease

• Conflicting data exist for long-term mortality in patients with stable angina and acute coronary syndrome.

• Younger females show higher short-term mortality compared with male counterparts after acute myocardial infarction.

• Females carry higher hospital mortality after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction compared with male patients.

Sex-specific outcomes following coronary artery bypass graft

• Female sex is an independent predictor of poor perioperative outcome.

• Long-term survival is comparable to both males and females.

• Internal thoracic artery grafts are underutilized in females compared with male patients.

• Off-pump coronary artery bypass graft showed improved in-hospital survival in female patients.

Sex-specific outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention

• Differences in outcomes decreased over time from balloon angioplasty era through drug-eluting stent era.

• Both males and females have comparable long-term outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation.

Future perspective

Although limited in sample number of female gender and study design, current studies have shown somewhat diminished but persistent sex-based differences in clinical outcomes of patients with CHD despite adjustment for other risk factors. Along with the advent of evidence-based medicine in modern medical science and the rapid development of revascularization techniques and medical devices, well-designed future researches including sufficient number of female participants warrant to better understand sex-based differences in CHD. Furthermore, it would be essential that clinical trials and registries should report gender-specific outcomes in terms of treatment effect. And, it was also considered that future clinical practice guidelines might be tailored to be gender-specific for improving the efficient use of various treatment options and targeting at-risk populations of males and females. Most importantly, treating physician should recognize the possibility of sex-specific difference in treatment effect and prognosis and incorporate any opportunities to mitigate these differences in clinical practice

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 129(3), e28–e292 (2014).

- Bucholz EM, Butala NM, Rathore SS, Dreyer RP, Lansky AJ, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in long-term mortality after myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Circulation 130(9), 757–767 (2014).

- US Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health. Monitoring adherence to the NIH Policy on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research: comprehensive report: tracking of human subjects research as reported in the fiscal year 2009 and fiscal year 2010. http://orwh.od.nih.gov/resources/policyreports/index.asp

- US Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff: evaluation of sex differences in medical device clinical studies. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices

- Webb CM, Ghatei MA, Mcneill JG, Collins P. 17beta-estradiol decreases endothelin-1 levels in the coronary circulation of postmenopausal women with coronary artery disease. Circulation 102(14), 1617–1622 (2000).

- Airaksinen KE, Ikaheimo MJ, Linnaluoto M, Tahvanainen KU, Huikuri HV. Gender difference in autonomic and hemodynamic reactions to abrupt coronary occlusion. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 31(2), 301–306 (1998).

- Pepine CJ, Kerensky RA, Lambert CR et al. Some thoughts on the vasculopathy of women with ischemic heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47(3 Suppl.), S30–S35 (2006).

- Yang F, Minutello RM, Bhagan S, Sharma A, Wong SC. The impact of gender on vessel size in patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries. J. Int. Cardiol. 19(4), 340–344 (2006).

- Berger JS, Bairey-Merz CN, Redberg RF, Douglas PS, Tank DT. Improving the quality of care for women with cardiovascular disease: report of a DCRI Think Tank, March 8 to 9, 2007. Am. Heart J. 156(5), 816–825, 825.e1 (2008).

- Mark DB. Sex bias in cardiovascular care: should women be treated more like men? JAMA 283(5), 659–661 (2000).

- Daly C, Clemens F, Lopez Sendon JL et al. Gender differences in the management and clinical outcome of stable angina. Circulation 113(4), 490–498 (2006).

- Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: what a difference a decade makes. Circulation 124(19), 2145–2154 (2011).

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 364(9438), 937–952 (2004).

- Milner KA, Funk M, Richards S, Wilmes RM, Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM. Gender differences in symptom presentation associated with coronary heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 84(4), 396–399 (1999).

- Khan NA, Daskalopoulou SS, Karp I et al. Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome symptom presentation in young patients. JAMA Int. Med. 173(20), 1863–1871 (2013).

- Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ et al. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA 307(8), 813–822 (2012).

- Bairey Merz CN. Sex, Death and the Diagnosis Gap. Circulation 130(9), 740–742 (2014).

- Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N. Engl. J. Med. 342(16), 1163–1170 (2000).

- Brieger D, Eagle KA, Goodman SG et al. Acute coronary syndromes without chest pain, an underdiagnosed and undertreated high-risk group: insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Chest 126(2), 461–469 (2004).

- Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD et al. Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 341(4), 226–232 (1999).

- Hemingway H, Mccallum A, Shipley M, Manderbacka K, Martikainen P, Keskimaki I. Incidence and prognostic implications of stable angina pectoris among women and men. JAMA 295(12), 1404–1411 (2006).

- Steg PG, Greenlaw N, Tardif JC et al. Women and men with stable coronary artery disease have similar clinical outcomes: insights from the international prospective CLARIFY registry. Eur. Heart J. 33(22), 2831–2840 (2012).

- Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N. Engl. J. Med. 341(4), 217–225 (1999).

- Simon T, Mary-Krause M, Cambou JP et al. Impact of age and gender on in-hospital and late mortality after acute myocardial infarction: increased early risk in younger women: results from the French nation-wide USIC registries. Eur. Heart J. 27(11), 1282–1288 (2006).

- Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 302(8), 874–882 (2009).

- Champney KP, Frederick PD, Bueno H et al. The joint contribution of sex, age and type of myocardial infarction on hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Heart 95(11), 895–899 (2009).

- Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Peterson ED, Rogers WJ, Kiefe CI, Canto J. Sex differences in mortality after acute myocardial infarction: changes from 1994 to 2006. Arch. Int. Med. 169(19), 1767–1774 (2009).

- Andrikopoulos GK, Tzeis SE, Pipilis AG et al. Younger age potentiates post myocardial infarction survival disadvantage of women. Int. J. Cardiol. 108(3), 320–325 (2006).

- Nauta ST, Deckers JW, Van Domburg RT, Akkerhuis KM. Sex-related trends in mortality in hospitalized men and women after myocardial infarction between 1985 and 2008: equal benefit for women and men. Circulation 126(18), 2184–2189 (2012).

- Edwards FH, Carey JS, Grover FL, Bero JW, Hartz RS. Impact of gender on coronary bypass operative mortality. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 66(1), 125–131 (1998).

- Kim C, Redberg RF, Pavlic T, Eagle KA. A systematic review of gender differences in mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery and percutaneous coronary interventions. Clin. Cardiol. 30(10), 491–495 (2007).

- Vaccarino V, Abramson JL, Veledar E, Weintraub WS. Sex differences in hospital mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery: evidence for a higher mortality in younger women. Circulation 105(10), 1176–1181 (2002).

- Abramov D, Tamariz MG, Sever JY et al. The influence of gender on the outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 70(3), 800–805; discussion 806 (2000).

- Edwards FH, Ferraris VA, Shahian DM et al. Gender-specific practice guidelines for coronary artery bypass surgery: perioperative management. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 79(6), 2189–2194 (2005).

- Takagi H, Manabe H, Umemoto T. A contemporary meta-analysis of gender differences in mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am. J. Cardiol. 106(9), 1367 (2010).

- Alam M, Lee VV, Elayda MA et al. Association of gender with morbidity and mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. A propensity score matched analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 167(1), 180–184 (2013).

- Blankstein R, Ward RP, Arnsdorf M, Jones B, Lou YB, Pine M. Female gender is an independent predictor of operative mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: contemporary analysis of 31 Midwestern hospitals. Circulation 112(9 Suppl.), I323–I327 (2005).

- Bukkapatnam RN, Yeo KK, Li Z, Amsterdam EA. Operative mortality in women and men undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (from the California Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Outcomes Reporting Program). Am. J. Cardiol. 105(3), 339–342 (2010).

- Nalysnyk L, Fahrbach K, Reynolds MW, Zhao SZ, Ross S. Adverse events in coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) trials: a systematic review and analysis. Heart 89(7), 767–772 (2003).

- Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 16(1), 9–13 (1999).

- Shahian DM, O’brien SM, Filardo G et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1--coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann. Thorac.Surg. 88(1 Suppl.), S2–S22 (2009).

- Jacobs AK, Kelsey SF, Brooks MM et al. Better outcome for women compared with men undergoing coronary revascularization: a report from the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI). Circulation 98(13), 1279–1285 (1998).

- Guru V, Fremes SE, Austin PC, Blackstone EH, Tu JV. Gender differences in outcomes after hospital discharge from coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation 113(4), 507–516 (2006).

- Saxena A, Dinh D, Smith JA, Shardey G, Reid CM, Newcomb AE. Sex differences in outcomes following isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery in Australian patients: analysis of the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons Cardiac Surgery Database. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 41(4), 755–762 (2012).

- Ahmed WA, Tully PJ, Knight JL, Baker RA. Female sex as an independent predictor of morbidity and survival after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 92(1), 59–67 (2011).

- Tabata M, Grab JD, Khalpey Z et al. Prevalence and variability of internal mammary artery graft use in contemporary multivessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery: analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Database. Circulation 120(11), 935–940 (2009).

- Otsuka F, Yahagi K, Sakakura K, Virmani R. Why is the mammary artery so special and what protects it from atherosclerosis? Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2(4), 519–526 (2013).

- Loop FD, Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM et al. Influence of the internal-mammary-artery graft on 10-year survival and other cardiac events. N. Engl. J. Med. 314(1), 1–6 (1986).

- Campeau L, Enjalbert M, Lesperance J et al. The relation of risk factors to the development of atherosclerosis in saphenous-vein bypass grafts and the progression of disease in the native circulation. A study 10 years after aortocoronary bypass surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 311(21), 1329–1332 (1984).

- Edwards FH, Clark RE, Schwartz M. Impact of internal mammary artery conduits on operative mortality in coronary revascularization. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 57(1), 27–32 (1994).

- Hammar N, Sandberg E, Larsen FF, Ivert T. Comparison of early and late mortality in men and women after isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery in Stockholm, Sweden, 1980 to 1989. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 29(3), 659–664 (1997).

- Aldea GS, Gaudiani JM, Shapira OM et al. Effect of gender on postoperative outcomes and hospital stays after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 67(4), 1097–1103 (1999).

- Gansera B, Gillrath G, Lieber M, Angelis I, Schmidtler F, Kemkes BM. Are men treated better than women? Outcome of male versus female patients after CABG using bilateral internal thoracic arteries. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 52(5), 261–267 (2004).

- Weiss AJ, Zhao S, Tian DH, Taggart DP, Yan TD. A meta-analysis comparing bilateral internal mammary artery with left internal mammary artery for coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2(4), 390–400 (2013).

- Benedetto U, Amrani M, Gaer J et al. The influence of bilateral internal mammary arteries on short- and long-term outcomes: A propensity score matching in accordance with current recommendations. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 148(6), 2699–2705 (2014).

- Smith T, Kloppenburg GT, Morshuis WJ. Does the use of bilateral mammary artery grafts compared with the use of a single mammary artery graft offer a long-term survival benefit in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery? Int. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 18(1), 96–101 (2014).

- Vieira De Melo RM, Hueb W, Rezende PC et al. Comparison between off-pump and on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with severe lesions at the circumflex artery territory: 5-year follow-up of the MASS III trial. Eur. J. Cadiothorac. Surg. 47(3), 455–458 (2014).

- Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. N. Engl.J. Med. 361(19), 1827–1837 (2009).

- Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D et al. Effects of off-pump and on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 1 year. N. Engl. J. Med. 368(13), 1179–1188 (2013).

- Hueb W, Lopes NH, Pereira AC et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized comparison between off-pump and on-pump stable multivessel coronary artery bypass grafting. The MASS III Trial. Circulation 122(11 Suppl.), S48–S52 (2010).

- Puskas JD, Kilgo PD, Kutner M, Pusca SV, Lattouf O, Guyton RA. Off-pump techniques disproportionately benefit women and narrow the gender disparity in outcomes after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation 116(11 Suppl.), I192–I199 (2007).

- Mack MJ, Brown P, Houser F et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery in a matched sample of women: a comparison of outcomes. Circulation 110(11 Suppl. 1), II1–II6 (2004).

- Brown PP, Mack MJ, Simon AW et al. Outcomes experience with off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery in women. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 74(6), 2113–2119; discussion 2120(2002).

- Fu SP, Zheng Z, Yuan X et al. Impact of off-pump techniques on sex differences in early and late outcomes after isolated coronary artery bypass grafts. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 87(4), 1090–1096 (2009).

- Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Dirschinger J, Bollwein H, Neumann FJ, Schomig A. Differences in prognostic factors and outcomes between women and men undergoing coronary artery stenting. JAMA 284(14), 1799–1805 (2000).

- Kelsey SF, James M, Holubkov AL, Holubkov R, Cowley MJ, Detre KM. Results of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in women. 1985–1986 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Coronary Angioplasty Registry. Circulation 87(3), 720–727 (1993).

- Malenka DJ, O’Connor GT, Quinton H et al. Differences in outcomes between women and men associated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. A regional prospective study of 13,061 procedures. Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Circulation 94(9 Suppl.), II99–II104 (1996).

- Chauhan MS, Ho KK, Baim DS, Kuntz RE, Cutlip DE. Effect of gender on in-hospital and one-year outcomes after contemporary coronary artery stenting. Am. J. Cardiol. 95(1), 101–104 (2005).

- Jacobs AK, Johnston JM, Haviland A et al. Improved outcomes for women undergoing contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Dynamic registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 39(10), 1608–1614 (2002).

- Berger JS, Sanborn TA, Sherman W, Brown DL. Influence of sex on in-hospital outcomes and long-term survival after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. Heart J. 151(5), 1026–1031 (2006).

- Duvernoy CS, Smith DE, Manohar P et al. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) percutaneous coronary intervention registry. Am. Heart J. 159(4), 677–683 (2010).

- Mikhail GW, Gerber RT, Cox DA et al. Influence of sex on long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention with the paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent: results of the “TAXUS Woman” analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 3(12), 1250–1259 (2010).

- Anderson ML, Peterson ED, Brennan JM et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of coronary stenting in women versus men: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services cohort. Circulation 126(18), 2190–2199 (2012).

- Onuma Y, Kukreja N, Daemen J et al. Impact of sex on 3-year outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention using bare-metal and drug-eluting stents in previously untreated coronary artery disease: insights from the RESEARCH (Rapamycin-Eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) and T-SEARCH (Taxus-Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) Registries. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2(7), 603–610 (2009).

- Abbott JD, Vlachos HA, Selzer F et al. Gender-based outcomes in percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents (from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry). Am. J. Cardiol. 99(5), 626–631 (2007).

- Stefanini GG, Baber U, Windecker S et al. Safety and efficacy of drug-eluting stents in women: a patient-level pooled analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 382(9908), 1879–1888 (2013).

- Stefanini GG, Kalesan B, Pilgrim T et al. Impact of sex on clinical and angiographic outcomes among patients undergoing revascularization with drug-eluting stents. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 5(3), 301–310 (2012).

- Park DW, Kim YH, Yun SC et al. Sex difference in clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in Korean population. Am. Heart J. 167(5), 743–752 (2014).

• Excellent review summarizing the alteration of the evidences in cardiovascular disease prevention.

• A worldwide clinical study evaluating the effect of risk factor on myocardial infarction.

• Key clinical study suggesting the mortality excess in younger female after acute myocardial infarction.

• The largest registry comparing the utilization rate of internal mammary artery between both sexes.

• Study suggesting that improved devices may have improved the outcomes in female with coronary heart disease.