Review Article - Imaging in Medicine (2015) Volume 7, Issue 1

Stenting in malignant superior vena cava syndrome review advances: in interventional radiology

Poul Erik Andersen* & Stevo DuvnjakDepartment of Radiology, Odense University Hospital and University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

- Corresponding Author:

- Poul Erik Andersen

Department of Radiology

Odense University Hospital and University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Tel: 6550 1000

E-mail: p.e.andersen@rsyd.dk

Abstract

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is a clinical syndrome which is caused by obstruction or compression of SVC and characterized by congestion and edema of upper body, upper extremities, and face, dilatation of neck, arm, and chest wall veins, respiratory distress, and cyanosis and the patients may experience cough, dyspnoea, haemoptysis, dysphagia, chest pain, headache, visual disturbance, convulsions and coma [1,2]. SVC syndrome may be caused by indwelling catheters, pacemaker wires or fibrosing mediastinitis [3-5] but 90 – 95% of the cases are caused by lung or mediastinal malignant tumors [6]. In these cases tIndication andhe aim of endovascular stent implantation is palliative and to alleviate the patients’ symptoms. It has been used in stenosis and obstruction of SVC for more than two decades [7,8]. Stent has become widely accepted in the management of malignant SVC obstruction and is now an accepted therapy as treatment of malignant SVC obstruction especially in advanced lung cancer and mediastinal tumours. Stenting in malignant SVC obstruction is increasingly been performed as it offers rapid relief of symptoms and gives the patients a better quality of life during their limited life expectancies due to the malignant disease itself.

Keywords

Superior vena cava syndrome; stent; treatment; palliative; interventional radiology; mediastinum neoplasms

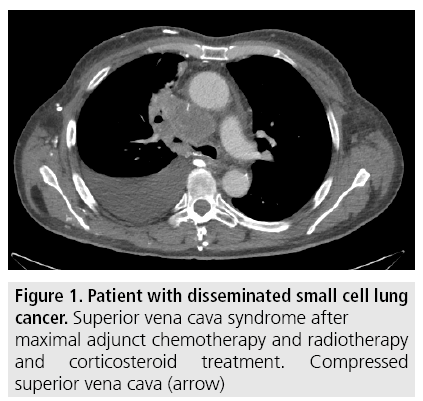

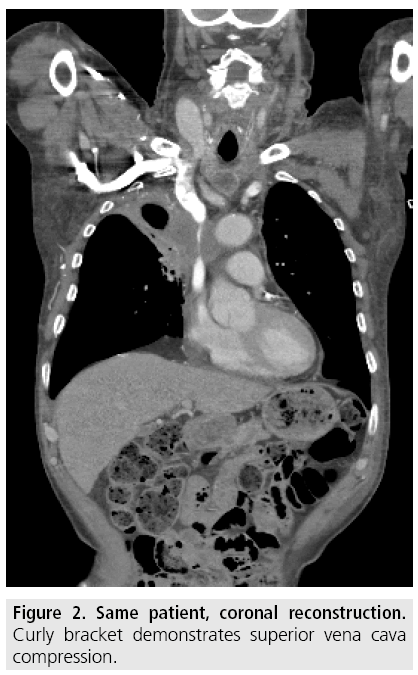

Radiological examinations

Compression and obstruction of SVC is verified by contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) which is performed before intervention to give accurate diagnosis and to demarcate the extent, level and cause of SVC obstruction as well as possible thrombus formation (FIGURES 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Patient with disseminated small cell lung cancer. Superior vena cava syndrome after maximal adjunct chemotherapy and radiotherapy and corticosteroid treatment. Compressed superior vena cava (arrow)

Interventional technique

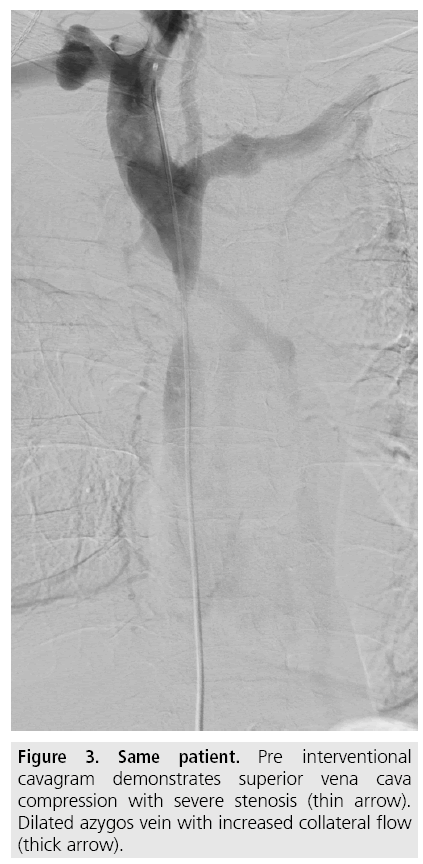

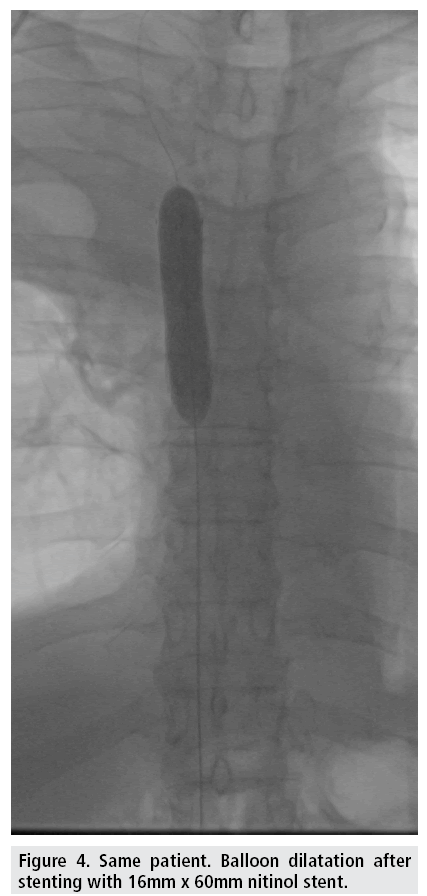

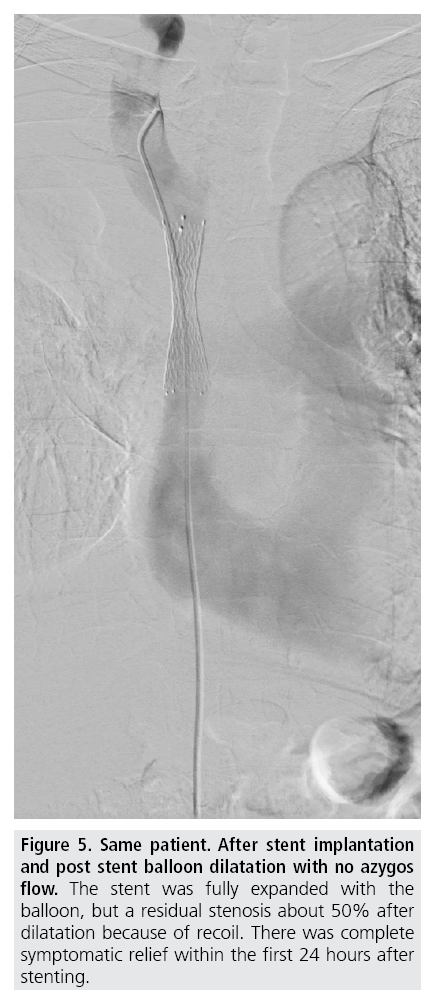

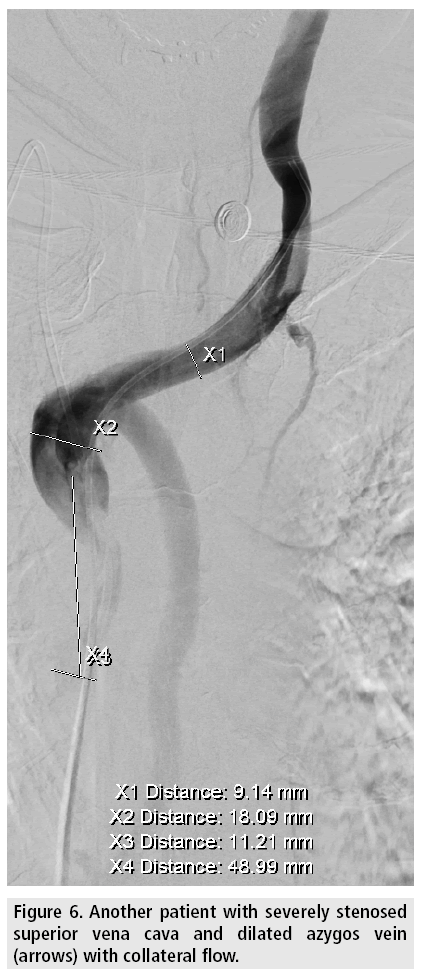

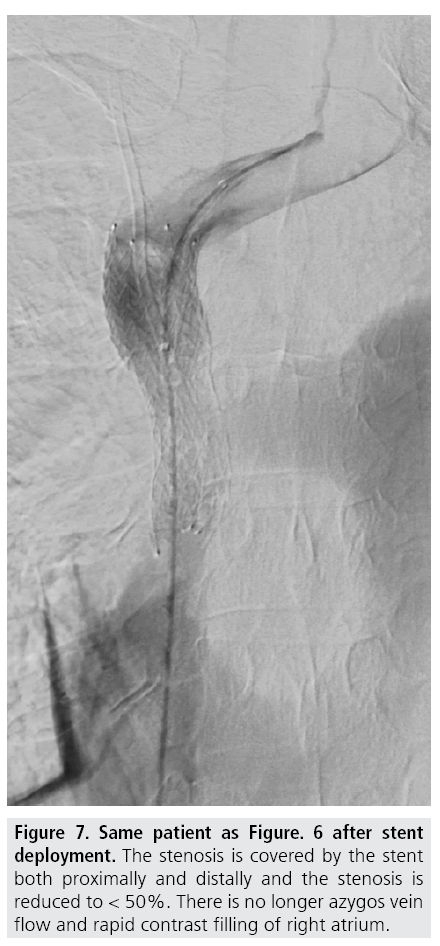

Venous access is gained under local analgesia, typically through the right femoral vein, and alternatively through the left femoral vein or through either of the internal jugular veins. Stenotic lesions are crossed with a 5F catheter over a hydrophilic guide wire. A superior vena cavagram is performed prior to the intervention to define the landing zone for the stent proximally and distally (FIGURE 3) as well as after stent deployment (FIGURES 4 and 5). If the obstruction involves both brachiocephalic veins, it is recommended to place stents in only one of these and in the SVC as stenting of both brachiocephalic veins may result in higher complication rates and lower survival [9,10]. If possible, stents are deployed so the obstruction is covered and there is at least 1 cm of diseasefree vessel at both ends [1] (FIGURES 6 and 7).

Figure 3: Same patient. Pre interventional cavagram demonstrates superior vena cava compression with severe stenosis (thin arrow). Dilated azygos vein with increased collateral flow (thick arrow).

Figure 5: Same patient. After stent implantation and post stent balloon dilatation with no azygos flow. The stent was fully expanded with the balloon, but a residual stenosis about 50% after dilatation because of recoil. There was complete symptomatic relief within the first 24 hours after stenting.

There is no agreement concerning balloon dilatation before or after deployment of stent (FIGURE 4). Predilatation might have an increased potential risk of pulmonary embolizations especially if there is thrombus formation but may be necessary to allow passage of the stent delivery system through the stenosis/occlusion. It is recommended to oversize the stent by 10–20 % compared with the normal diameter of SVC proximal and distal to the stenosis. Bolus of 5,000 units of unfractionated heparin (70 IU/kg) is given during the procedure.

Nitinol stents are recommended, as opposed to stainless steel stents, because recurrence of SVC syndrome has been found to significantly increase with use of stainless steel stents compared with nitinol stents [11]. There is no evidence that one type of nitinol stent is better than the others [12]. One non-randomized study has evaluated outcomes of covered stents and compared them with uncovered stents in patients with malignant SVC syndrome [13]. They found that covered stents seemed to be superior to uncovered stents in terms of stent patency but did not differ in terms of clinical success. Bare stents are generally being used, but covered stents might be preferred in cases of suspicious malignant invasion of SVC with risk of vessel perforation but the bigger introducing systems and higher price of the covered device is not in favor of covered stent for general use in SVC syndrome instead of bare stents. As there are no randomized studies, it is unclear whether patients in stenting studies are selected in any particular way [14].

Technical success and clinical outcome

Technical success defined as stent deployment in the intended location with < 50% residual stenosis and no adverse events or complications which can be ascribe to the procedure itself during the procedure or within the first 48 hours after the procedure. This can usually be achieved in more than 90% of the cases [1,15,16]. Technical failure is mostly associated with SVC occlusion, bilateral innominate vein occlusion and thrombus. Peri- and postprocedural complication rates are about 6%, and mortality rate approximately 3% [1,17-19].

The clinical outcome with relief of SVC symptoms within the first 48 hours and no associated complications is more than 90% [1,14-16,19,20]. The recurrence rate is about 10% but a high proportion of these patients can be treated with re-intervention. Stenting seems to be the most effective and rapid treatment for the relief of SVC symptoms [14]. Stenting provides immediate and sustained symptomatic relief that lasts until death in this set of patients with a short life expectancy. It is debated whether stent deployment should be used in an earlier phase of SVC syndrome before manifest symptoms or wait until the patients have received maximal adjunct chemotherapy and radiotherapy [11].

■Aftercare

There is no consensus on postprocedural anticoagulation strategy in the literature with regard to a compromise balancing risk of recurrent thrombosis and prevention of hemorrhagic complications [1,11,14]. Antiplatelet aggregation regimen with aspirin after the procedure is generally recommended [10,21]. There is no routine follow-up imaging protocol in the literature.

■Complications

There is a low reported morbidity related to cava superior stenting, and complications are uncommon. Peri- and postprocedural complications related to SVC stenting rates are about 6%, and mortality rate approximately 3% [1,17-19].

Stent fracture, stent thrombosis and stent infection have been described. There have been published case reports on stent migration [22,23] and pericardial tamponade [24-26]. Lung emboli may also be a potential complication.

Conclusion

Stenting of SVC has become widely accepted as palliative treatment for SVC syndrome in malignant diseases. Outcomes and complications compare very favorably with standard therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy [1].

In advanced lung cancer, data support the use of stenting for relapse of SVC syndrome or persistent SVC syndrome following initial standard radio-chemotherapy. Randomized studies are required comparing standard radiochemotherapy and stenting for persisting or recurrent SVC syndrome with initial stenting followed by standard radio-chemotherapy [14].

Stent implantation is a minimally invasive method performed with low mortality and morbidity.

References

- Uberoi R. Quality assurance guidelines for superior vena cava stenting in malignant disease. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 29, 319- 322 (2006).

- Wan JF, Bezjak A. Superior vena cava syndrome. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 24, 501-513 (2010).

- Warren P, Burke C. Endovascular management of chronic upper extremity deep vein thrombosis and superior vena cava syndrome. Semin. Intervent. Radiol. 28, 32-38 (2011).

- Klop B, Scheffer MG, McFadden E et al. Treatment of pacemaker-induced superior vena cava syndrome by balloon angioplasty and stenting. Neth. Heart. J. 19, 41-46 (2011).

- Albers EL, Pugh ME, Hill KD et al. Percutaneous vascular stent implantation as treatment for central vascular obstruction due to fibrosing mediastinitis. Circulation. 123, 1391-1399 (2011).

- Lanciego C, Pangua C, Chacón JI et al. Endovascular stenting as the first step in the overall management of malignant superior vena cava syndrome. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 193, 549-558 (2009).

- Charnsangavej C, Carrasco CH, Wallace S et al. Stenosis of the vena cava, preliminary assessment of treatment with expandable metallic stents. Radiology. 161, 295-298 (1986).

- Rösch J, Bedell JE, Putnam J et al. Gianturco expandable wire stents in the treatment of superior vena cava syndrome recurring after maximum-tolerance radiation. Cancer 60, 1243-1246 (1987).

- Dinkel HP, Mettke B, Schmid F et al. Endovascular treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome, is bilateral wallstent placement superior to unilateral placement? J. Endovasc. Ther. 10, 788-797 (2003).

- Lanciego C, Chacón JL, Julián A et al. Stenting as first option for endovascular treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 177, 585-593 (2001).

- Fagedet D, Thony F, Timsit J-F et al. Endovascular treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome, results and predictive factors of clinical efficacy. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 36, 140-149 (2013).

- Andersen PE, Midtgaard A, Brenøe AS et al. A new nitinol stent for use in superior vena cava syndrome. Initial clinical experience. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. (Torino) (2015).

- Gwon DI, Ko GY, Kim JH et al. Malignant superior vena cava syndrome, a comparative cohort study of treatment with covered stents versus uncovered stents. Radiology. 266, 979- 987 (2013).

- Rowell NP, Gleeson FV Steroids. Radiotherapy, chemotherapy and stents for superior vena caval obstruction in carcinoma of the bronchus, a systematic review. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 14, 338-351 (2002).

- Mokry T, Bellemann N, Sommer CM et al. Retrospective study in 23 patients of the self-expanding sinus-XL stent for treatment of malignant superior vena cava obstruction caused by non-small cell lung cancer. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 26, 357-365 (2015).

- Cho TH, Janho K, Mohan IV. The role of stenting the superior vena cava syndrome in patients with malignant disease. Angiology. 62, 248-252 (2011).

- Urruticoechea A, Mesía R, Domínguez J et al. Treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome by endovascular stent insertion. Experience on 52 patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 43, 209-214 (2004).

- Sobrinho G, Aguiar P. Stent placement for the treatment of malignant superior vena cava syndrome - a single-center series of 56 patients. Arch. Bronconeumol. 50, 135-140 (2014).

- Andersen PE, Duvnjak S. Palliative treatment of superior vena cava syndrome with nitinol stents. Int. J. Angiol. 23, 255-262 (2014).

- Duvnjak S, Andersen P (2011) Endovascular treatment of superior vena cava syndrome. Int Angiol 30, 458-461.

- Gross CM, Krämer J, Waigand J et al. Stent implantation in patients with superior vena cava syndrome. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 169, 429-432 (1997).

- Anand G, Lewanski CR, Cowman SA et al. Superior vena cava stent migration into the pulmonary artery causing fatal pulmonary infarction. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 34(2), S198-S201 (2011).

- Linda S, Augustin P, Anne-Claire T et al. Unusual migration of a vena cava stent into the pulmonary artery because of tumor reduction after chemotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 8, 1585- 1586 (2013).

- Ploegmakers MJ, Rutten MJ. Fatal pericardial tamponade after superior vena cava stenting. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 32, 585-589 (2009).

- Da Ines D, Chabrot P, Motreff P et al. Cardiac tamponade after malignant superior vena cava stenting, Two case reports and brief review of the literature. Acta. Radiol. 51, 256-259 (2010).

- Khalid I, Omari M, Khalid TJ et al. Pericardial tamponade after superior vena cava stent, are nitinol stents safe? Asian. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 18, 294-296 (2010).