Review Article - Journal of Experimental Stroke & Translational Medicine (2011) Volume 4, Issue 1

Targeting ischemic penumbra Part II: selective drug delivery using liposome technologies

- *Corresponding Authors:

- Shimin Liu, M.D., Ph.D

Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine

715 Albany street, C329, Boston, MA02118

Tel: 617-638-7776

Fax: 617-638-5354

E-mail: lius@bu.edu - H. Richard Winn, M.D

Director of Neurosurgery, 130 East 77th Street

Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, New York 10075

Tel: 212-434 3673

Fax: 212-434 2787

E-mail: hrwinn@Lenoxhill.net

Abstract

In the present review (part II), we discuss the challenges and promises of selective drug delivery to ischemic brain tissue by liposome technologies. In part I of this serial review, we proposed “selective drug delivery to ischemic brain tissue” as a technique for neuroprotective treatment of acute ischemic stroke. To be effective, drugs must pass a series of barriers to arrive at ischemic brain. Brain ischemia results in metabolic and structur-al changes in the ischemic region, which cause additional obstacles for drug delivery. Liposome drug delivery system can pass these barriers and selectively target ischemic tissue by utilizing ischemia-induced changes in metabolism and molecular structure.

Keywords

Penumbra; drug delivery; liposome; pH-sensitive; blood brain barrier.

Acute ischemic stroke causes irreversible injury in the ischemic core, but reversible injury in the perifocal zone, the penumbra.(Astrup et al. 1981; Ebinger et al. 2009; Memezawa et al. 1992) Conventional drug delivery methods cause unwanted drug exposure to other tissue or brain regions. Because of limited blood supply to ischemic penumbra region, systemic high dose is often required for a drug to reach therapeutic levels in ischemic tissue, which may cause severe side effects and toxicity. Advanced drug delivery system using liposome techniques may achieve effective regional drug level without increasing systemic dose. Liposomal nanocarriers facilitate penetration of biological membrane, protect drugs from enzymatic and chemical degradation and albumin binding, and minimize drug exposures to nontarget tissue. (Jain 2007; Tiwari and Amiji 2006) Following paragraphs discuss the challenges of selective drug delivery to ischemic brain tissue and the promises of liposome technologies in stroke therapy.

The blood brain barrier

The blood brain barrier (BBB) consists of an endothelial enclosure and periendothelial accessories, which include pericytes, astrocytes, and a basal membrane. BBB strictly limits exchanges of substance between blood and the brain. The endothelial cells of the BBB lack fenestrations and have both tight junctions and adherens junctions between the cells (Bazzoni and Dejana 2004; Kniesel and Wolburg 2000; Schulze and Firth 1993). BBB prevents passive diffusion of hydrophilic molecules and allows diffusion of uncharged small molecules (Grieb et al. 1985; Levin 1980). A thin basement membrane (i.e. basal lamina) surrounds the endothelial cells and pericytes supporting the abluminal surface of the endothelium. Astrocytes further encase this structure with endfeet interspersed with pericytes. (Hellstrom et al. 2001; Kacem et al. 1998). The BBB protects brain from foreign substance, but it also strictly limits therapeutic agents entering the brain.

Because of the lipidic nature of all biological membranes, including brain endothelial cell membrane, lipophilic molecules can diffuse across BBB whilst hydrophilic molecules utilize transporter facilitated systems. (Pardridge 1999) Active transport of some endogenous or exogenous hydrophilic molecules crossing BBB can be in either influx or efflux directions. (Ohtsuki and Terasaki 2007) Some of these transporters, such as for amino acids, monocarboxylic acids, organic cations, hexoses, nucleosides, peptides, have been well studied and molecularly identified. We refer the reader to the excellent review articles (Tamai and Tsuji 2000; Tsuji 2005) for more information of transport assisted passage of BBB.

BBB during cerebral ischemia

Cerebral ischemia causes BBB damage and temporary BBB disruption. However, this temporary BBB opening causes edema, hemorrhagic transformation, and additional brain injury, therefore, it cannot be used for neuroprotective purpose. The area of the BBB disruption depends on injury intensity, injury type, and presence or absence of reperfusion. The BBB opening during ischemia in the absence of reperfusion occurs when the ischemic damage is already irreversible. For example, gadoliniumdiethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) extravasations was found grossly visible between 4.5 and 6 h after permanent MCAO (Kastrup et al. 1999). At this time, ischemic brain injury has already happened and is mostly irreversible. Reperfusion induced BBB disruption occurs after 3 and 48 hours of 2-h MCAO with reperfusion, with maximal opening at 48 hours and returns to normal by 14 days (Rosenberg et al. 1998). Gelatinase A (MMP-2) and TIMP-2 are associated with reperfusion induced BBB disruption(Rosenberg et al. 1998). After transient 20-min MCAO BBB disruption peaks at day 7 and resolves at day 14 after ischemia (Abulrob et al. 2008). BBB disruption during reperfusion stage is believed to be a precursor to hemorrhagic transformation (HT) and poor outcome (Latour et al. 2004), which should be treated with adjunctive therapies.

Methods for transducing the blood brain barrier

Traditional methods for opening BBB are invasive, inefficient, and nonselective. Transient osmotic opening of the BBB by arabinose or mannitol (Shinohara et al. 1979; Siegal et al. 2000), shunts (Zlotnik et al. 2008), or implanting microspheres (Beduneau et al. 2007; Emerich et al. 1999) to deliver therapeutic agents are invasive methods and have potential sideeffects. Osmotic agents can cause accumulation of mannitol in the cerebral tissue and increase edema, whilst implantations require surgery (Kaufmann and Cardoso 1992; Maioriello et al. 2002). These methods do not selectively open BBB for drug delivery or selectively target tissue.

More advanced methods for CNS drug delivery include altering the molecular structure of drugs to increase their membrane permeability, fusing the drug molecule with cell penetrating peptides, and encapsulating drugs into liposomal nanocarriers. Drugs can also compete to use a carrier system if their structure mimics that of an endogenous molecule. Drugs that cannot use an endogenous transport system may be fused to a molecule, such as transferrin or glucose (Rajkumar et al. 1995), which can be effectively transported across the BBB. In addition, monoclonal antibodies can be utilized to transport some drugs across the BBB via a receptormediated transport system (Lee et al. 2000; Pardridge 2005). In a similar manner, many cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) have been used for CNS drug delivery by conjugating to functioning therapeutic agents for cerebral ischemia (Esneault et al. 2008; Eum et al. 2004; Fan et al. 2006). Nanoliposomes and other nanoparticles can be utilized to deliver genes, proteins/peptides, and many other agents across the BBB. Nanoliposomes are engineered to enclose hydrophilic or ambiphilic agents within one or two lipid bilayers, similar to biological membranes.

The nanoliposome crosses the BBB by one of three methods: passive diffusion, endocytosis, or assisted passage with brain targeting ligands (Beduneau et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2010; Markoutsa et al. 2011; Tamaru et al. 2010; Wong et al. 2010). These advanced methods for CNS drug delivery transduce BBB for a particular therapy, but they are not readily tissue selective or cell type selective. It is possible to achieve significant improvements on the delivery specificity and efficiency by extensive modification and optimization of these methods. Selective BBB transduction for drug delivery that targets the diseased tissue will improve delivery efficiency and reduce adverse effect, and potentially can be used in ischemic stroke and other CNS disorders.

Compromised blood supply and shrinkage of extracellular space

In addition to the challenge of BBB, ischemic brain tissue also has compromised blood flow that can further limit efficient drug delivery through blood supply. For example, the regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in the inner penumbra is only about 15 ml/100g/min (Murphy et al. 2006; Ohashi et al. 2005). Moreover, the extracellular space (ECS) is also decreased during ischemia (Thorne and Nicholson 2006; Zoremba et al. 2008). Ischemia causes cytotoxic edema that increases cell volume by 12% and reduces ECS by 50%. (Homola et al. 2006) Theoretically, large dose will be needed for reaching an effective regional drug concentration; this increased dose may lead to severe drug toxicity. Many neuroprotectants have been tested effective in animal studies, but they cannot be used in stroke patients at effective dose because of drugrelated severe toxicity.

The advantages of liposomal drug delivery system

Advanced technologies, such as pH-sensitive nanoliposomes with enhanced BBB penetration and tissue selectivity, hold promises for ischemic stroke therapies. The lipid layer affords nanoliposomes BBB permeability for their encapsulated contents. Moreover, these liposomal nanocarriers can acquire additional features through further modification, such as long circulating time, enhanced BBB penetration and ischemic tissue selectivity. The advantages of using nanoliposomes also include: 1). maintaining drugs in active state when being encapsulated inside the nanoliposome; 2). minimizing exposure to nontarget tissue when tissue selective liposomes being used; 3). providing a protective shell for the encapsulated contents, which prevents drugs from non specific binding and enzymatic digestion; 4). being able to afford a high intraliposomal drug concentration. Therefore, nanoliposomes could be used as a basic means for drug delivery to ischemic stroke penumbra.(Jain 2007; Tiwari and Amiji 2006)

Possibility of selective drug delivery to penumbral tissue

Brain ischemia causes a metabolic shift towards anaerobic glycolysis, resulting in a lower intracellular pH in the ischemic brain tissue. Targeting at this property of ischemic brain tissue, liposomal nanocarriers may be optimized to selectively release their contents under acidic condition (Collins et al. 1989) similar to the microenvironment of ischemic brain tissue (pH<6.75) (Anderson et al. 1999). The fusogenic property of dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine and transactivator of transcription (TAT) peptide will facilitate liposomes escaping from endosomes/lysosomes and normal cells (Boomer et al. 2009; Hatakeyama et al. 2009). These liposomes will release their cargos when they reach cytosols of ischemic cells that have a pH of around 6.75. The pH difference between extracellular and intracellular space in ischemic tissue is usually less than 0.5 unit in normoglycemic rats (Nedergaard et al. 1991), therefore, a portion of pH sensitive liposomes will deliver their cargos in the interstitial space.

These liposomal nanocarriers can gain additional features by incorporating functional molecules onto their membrane surfaces. Stroke homing peptide (Hong et al. 2008) may be useful for selective drug delivery to ischemic brain tissue.

The strategies for liposomal drug delivery to ischemic penumbra

Currently there are no specially tailored nanolipo somes available for targeting ischemic stroke penumbra. A nanosized pH-sensitive liposome commonly has 3-5 structural components, which include a basic lipid, a balancer, a stabilizer, optional function peptides, and an optional tracer. The basic lipid provides the sensitivity to acidic environment. The balancer is used to titrate pH-sensitivity to the desired level. The stabilizer protects the nanoliposome from unwanted leakage and fusion. Optional function peptides may provide the nanoliposome additional abilities, such as enhanced BBB penetration and specific tissue targeting. Optional tracer can be a fluorescent lipid or fluorescent peptide.

The basic lipid DOPE

There are two basic lipids that provide nanolipo somes a sensitivity to acidic environment, the phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), and the dioleoylphos phatidylethanolamine (DOPE) (Drummond et al. 2000). PE based nanoliposomes tend to release their contents in a more acidic environment that may mimic ischemic core. DOPE based nanoliposomes can be optimized to release contents at mild acidic environment that may mimic ischemic penumbra. DOPE also has fusogenic property that facilitates liposomes escaping from endosomes and lysosomes (Boomer et al. 2009; Hatakeyama et al. 2009). The mild acidic activation and fusogenic property of DOPE plus residual blood flow in penumbral region give DOPE-based liposomes a higher chance of drug delivery to ischemic penumbra.

Balancers and stabilizers

N-succinyldioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (suc-DOPE), oleic acid (OA), palmitoylhomocysteine (PHC), cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHEMS), and 1,2-dioleoyl- or 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-3-succinylglycerol (DOSG or DPSG) are a few of the stabilizers that have been used to prepare pH-sensitive liposome formulations. CHEMS-balanced pH-sensitive nanoliposomes have been demonstrated for efficient intracellular delivery.(Costin et al. 2002) Poly (ethyleneglycol) (PEG) with different molecular weights is the most commonly used stabilizer and compatible with pH-sensitive nanoliposomes.

PEG coated pH-sensitive nanoliposomes for long circulatingn time

Conventional or plain nanoliposomes are rapidly removed from circulation by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and accumulate in the liver and spleen (Allen 1994; Cowens et al. 1993; Rahman et al. 1990), which limits their clinical applications. Recent progress in microencapsulation showed that introducing poly(ethyleneglycol) (PEG) onto nanoliposome surface can prevent nanoliposomes from opsonization (Allen et al. 1991; Blume and Cevc 1990; Blume and Cevc 1993; Torchilin et al. 1994), resulting in a long circulating time (Klibanov et al. 1990). PEG coated pH-sensitive nanoliposomes can be constructed using low pH-cleavable PEG or DSPE-PEG of a proper molar ratio. The working mechanisms of PEGylated pH-sensitive nanoliposomes have been well illustrated. (Romberg et al. 2008; Sawant et al. 2006) The low pH-cleavable PEG is linked to its anchor by some special linkers, which include Diorthoester, Orthoester, Vinylether, Phosphoramidate, Hydrazone, bthiopropionate. (Romberg et al. 2008) The DSPE-PEG coating is commonly used for constructing pH-sensitive liposomes. (Hong et al. 2002; Simoes et al. 2001; Slepushkin et al. 1997) The feature of pH-dependent release is determined by DOPE/CHEMS ratio and PEG percentage. When DSPE-PEG is anchored on to pH-sensitive liposome with a proper molar ratio, it may be randomly extracted and shed from liposome surface allowing uptake by cells when its anchor, the base lipid, becomes unstable in low pH environment. The fusogenic property of DOPE lipid (Boomer et al. 2009; Hatakeyama et al. 2009) may work synergically with TAT peptide to initiate internalization and intracellular delivery. The methodologies for construction and purification of DSPE-PEG-coated nanoliposomes have been well established. (Liang et al. 2004).

Functional peptides

Functional peptides for nanoliposomes can be classified into three categories: 1). cellpenetrating peptides (CPPs); 2). pHdependent fusion peptides; and 3). special function peptides. Here we just list the names of these peptides. More detailed and condensed information is available in related review papers(Deshayes et al. 2005; Drummond et al. 2000). CPPs include TAT, octarganine/R8, penetratin/ AntpHD, FGF/MTS, VP22, PEP-1, DynA, transportan, MAP, pegelin/SynB, pVEC, KALA, ppTG20, P1, MPG, trimer, and PrP. pH-dependent peptides and toxins include HA2, E1, G1/G2, G1/G2, G, E, gp36, TH8/TH9, GALA, SFP, Poly(Glu-Aiba-Leu-Aib, EGLA-I, EGLA-II, JTS1, VP-1, INF3, INF5, INF7, INF8, INF9, INF10, HA peptide, D4, E5, E5L, E5NN, E5CC, E5P, E5CN, AcE4K, poly(llysine), poly(lhistidine), poly(acrylic acid) derivatives, succinylated poly(glycidol)s, and copolymers of Nisopropylacrylamide (NIPAM). It may be practical to use CHEMS for titrating nanoliposomes to a desired pH-sensitivity and leave these pH-sensitive peptides as alternative approaches. Lysosomesdisrupting peptides have been reported to enhance intracellular delivery efficiency (Baru et al. 1998). Stroke homing peptide is a special peptide that has been reported recently being able to targeting ischemic brain tissue. This peptide has the sequence "CLEVSRKNC"

TAT peptide targeted pH-sensitive nanoliposomes for BBB transduction. The human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 transactivating transcriptional activator (HIV-1 TAT protein, an 86-mer polypeptide) (Frankel and Pabo 1988; Green and Loewenstein 1988) has been shown the ability for inducing cell transduction. Certain small regions of such proteins (10–16-mers) called protein transduction domains (PTDs) are responsible for TAT protein induced cell transduction. The minimal PTD of the TAT protein comprises 11 amino acids (Tyr-Gly-Arg-Lys-Lys-Arg-Arg-Gln-Arg-Arg-Arg) functioning as a cell penetrating peptides (CPP). Fluorescently labeled TAT was visible throughout the brain 20 minutes after intraperitoneal (IP) administration in mice (Schwarze et al. 1999). Many other CPPs have also been discovered and synthesized (Deshayes et al. 2005). TAT peptide is the most widely used CPP among other CPPs for enhancing BBB penetration and for intracellular drug delivery (Herve et al. 2008). Moreover, relatively large 200-nm plain or polyethylene glycolcoated (PEGylated) nanoliposomes can be delivered into various cells by multiple TAT peptide molecules attached to the nanoliposome surface. (Hyndman et al. 2004; Levchenko et al. 2003; Torchilin 2002; Torchilin et al. 2001)

Stroke homing peptide. Recently, the CLEVSRKNC (single letter sequence for Cys-Leu-Glu-Val-Ser-Arg-Lys-Asn-Cys) peptide has been demonstrated to be selective for ischemic brain tissue. (Hong et al. 2008)This peptide was screened from a phage peptide library based on a T7 415-1b phage vector displaying CX7C (C, cysteine; X, random peptides)(Pasqualini and Ruoslahti 1996). The CLEVSRKNC-phage preferentially targeted ischemic stroke tissue after intravenous administration in a rat MCA occlusion model. Because the CLEVSRKNC peptide is displayed on the phage membrane, theoretically it should be compatible with nanoliposome membrane layers. This means that CLEVSRKNC peptide may be incorporated onto nanoliposomes layers in ways similar to TAT peptide (Hyndman et al. 2004; Levchenko et al. 2003; Torchilin 2002; Torchilin et al. 2001) for localized drug delivery to ischemic brain tissue.

Lipid and peptide tracers

Lipids and peptides can be conjugated with some fluorescent dye to trace the distribution of nanolipo somes in cells or tissue. Rhodamine and Tetramethyl Rhodamine (TRITC) are commonly used for this purpose, and the synthesis and conjugating process are commercially available.

Liposome size for penumbra drug delivery

Liposome size is one of the factors that influence in vivo liposome distribution and drug delivery. The in vivo extracellular space width in rat brain is estimated 38-64 nm (Thorne and Nicholson 2006), at least 2-fold greater than estimates from fixed tissue. Liposomes for brain drug delivery have been used in sizes of 50-150 nm (Chapat et al. 1991; Madhankumar et al. 2009), 64-73 nm (Xie et al. 2005), 120-147 nm (Puisieux et al. 1994), and 134-143 nm (Ko et al. 2009). Some of these liposomes sizes were bigger than extracellular space width. In such case, liposomes may mainly depend on endocytosis and transcellular route for drug delivery, similar to the mechanism that allows their passage through the BBB (Patel et al. 2009). Because of the shrinkage of extracellular space (Thorne and Nicholson 2006; Zoremba et al. 2008), relatively smallsized liposomes may facilitate interstitial diffusion in ischemic tissue; but a smaller size also increases the risk of potential pulmonary toxicity (Nel et al. 2006).

Concluding remarks

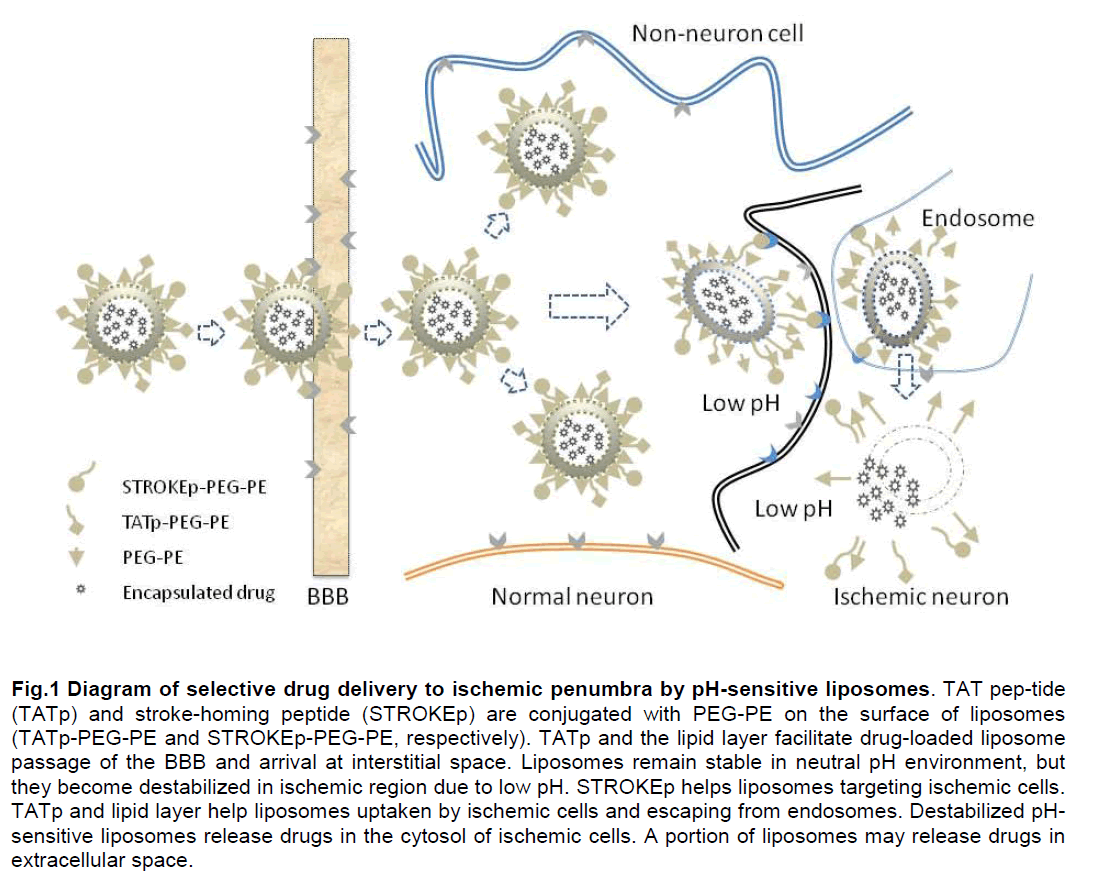

The inability to selectively deliver S therapeutic agents to brain tissue, especially during ischemic, has been a limitation in the treatment of stroke. However, advanced drug delivery tools provide a mechanism to overcome these difficulties in stroke therapy. Because ischemia causes an acidic environment and residual blood flow exists in ischemic penumbral region, liposomal delivery system with a low pH-dependent release feature can be used for targeting ischemic penumbra. The DOPE/CHEMS/DSPE-PEG system holds promises as a basic formula of pH-dependent liposomes for stroke treatment. Other peptides, such as TATp and stroke homing peptide (STROKEp) may provide added features for such system. The proposed working mechanism is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Diagram of selective drug delivery to ischemic penumbra by pH-sensitive liposomes. TAT peptide (TATp) and stroke homing peptide (STROKEp) are conjugated with PEG-PE on the surface of liposomes (TATp-PEG-PE and STROKEp-PEG-PE, respectively). TATp and the lipid layer facilitate drugloaded liposome passage of the BBB and arrival at interstitial space. Liposomes remain stable in neutral pH environment, but they become destabilized in ischemic region due to low pH. STROKEp helps liposomes targeting ischemic cells. TATp and lipid layer help liposomes uptaken by ischemic cells and escaping from endosomes. Destabilized pH-sensitive liposomes release drugs in the cytosol of ischemic cells. A portion of liposomes may release drugs in extracellular space.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grant 7R21NS065912-02, 5T32NS051147-02 and NS 21076-24.

Conflict of interest

None

References

- Abulrob A, Brunette E, Slinn J, Baumann E, Stanimirovic D. (2008) Dynamic analysis of the bloodbrain barrier disrulition in exlierimental stroke using time domain in vivo fluorescence imaging. Mol Imaging 7:248-262

- Allen TM. (1994) Longcirculating (sterically stabilized) liliosomes for targeted drug delivery. Trends liharmacol Sci 15:215-220

- Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemann C, Yau-Young A. (1991) Liliosomes containing synthetic liliid derivatives of lioly(ethylene glycol) show lirolonged circulation halflives in vivo. Biochim Biolihys Acta 1066:29-36

- Anderson RE, Tan WK, Meyer FB. (1999) Brain acidosis, cerebral blood flow, caliillary bed density, and mitochondrial function in the ischemic lienumbra. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 8:368-379

- Astruli J, Siesjo BK, Symon L. (1981) Thresholds in cerebral ischemia - the ischemic lienumbra. Stroke 12:723-725

- Baru M, Nahum O, Jaaro H, Sha'anani J, Nur I. (1998) Lysosome disruliting lielitide increases the efficiency of in vivo gene transfer by liliosomeencalisulated DNA. J Drug Target 6:191-199

- Bazzoni G, Dejana E. (2004) Endothelial cellto-cell junctions: molecular organization and role in vascular homeostasis. lihysiol Rev 84:869-901

- Beduneau A, Saulnier li, Benoit Jli. (2007) Active targeting of brain tumors using nanocarriers. Biomaterials 28:4947-4967

- Blume G, Cevc G. (1990) Liliosomes for the sustained drug release in vivo. Biochim Biolihys Acta 1029:91-97

- Blume G, Cevc G. (1993) Molecular mechanism of the liliid vesicle longevity in vivo. Biochim Biolihys Acta 1146:157-168

- Boomer JA, Qualls MM, Inerowicz HD, Haynes RH, liatri VS, Kim JM, Thomlison DH. (2009) Cytolilasmic delivery of liliosomal contents mediated by an acidlabile cholesterolvinyl ether-liEG conjugate. Bioconjug Chem 20:47-59

- Chaliat S, Frey V, Clalieron N, Bouchaud C, liuisieux F, Couvreur li, Rossignol li, Delattre J. (1991) Efficiency of liliosomal ATli in cerebral ischemia: bioavailability features. Brain Res Bull 26:339-342

- Chen H, Tang L, Qin Y, Yin Y, Tang J, Tang W, Sun X, Zhang Z, Liu J, He Q. (2010) Lactoferrinmodified lirocationic liliosomes as a novel drug carrier for brain delivery. Eur J liharm Sci 40:94-102

- Collins D, Maxfield F, Huang L. (1989) Immunoliliosomes with different acid sensitivities as lirobes for the cellular endocytic liathway. Biochim Biolihys Acta 987:47-55

- Costin GE, Trif M, Nichita N, Dwek RA, lietrescu SM. (2002) liH-sensitive liliosomes are efficient carriers for endolilasmic reticulumtargeted drugs in mouse melanoma cells. Biochem Biolihys Res Commun 293:918-923

- Cowens JW, Creaven liJ, Greco WR, Brenner DE, Tung Y, Ostro M, liilkiewicz F, Ginsberg R, lietrelli N. (1993) Initial clinical (lihase I) trial of TLC D-99 (doxorubicin encalisulated in liliosomes). Cancer Res 53:2796-2802

- Deshayes S, Morris MC, Divita G, Heitz F. (2005) Celllienetrating lielitides: tools for intracellular delivery of theralieutics. Cell Mol Life Sci 62:1839-1849

- Drummond DC, Zignani M, Leroux J. (2000) Current status of liH-sensitive liliosomes in drug delivery. lirog Liliid Res 39:409-460

- Ebinger M, De Silva DA, Christensen S, liarsons MW, Markus R, Donnan GA, Davis SM. (2009) Imaging the lienumbra - strategies to detect tissue at risk after ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurosci 16:178-187

- Emerich DF, Tracy MA, Ward KL, Figueiredo M, Qian R, Henschel C, Bartus RT. (1999) Biocomliatibility of lioly (DLlactide-co-glycolide) microsliheres imlilanted into the brain. Cell Translilant 8:47-58

- Esneault E, Castagne V, Moser li, Bonny C, Bernaudin M. (2008) D-JNKi, a lielitide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase, liromotes functional recovery after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience 152:308-320

- Eum WS, Kim DW, Hwang IK, Yoo KY, Kang TC, Jang SH, Choi HS, Choi SH, Kim YH, Kim SY, Kwon HY, Kang JH, Kwon OS, Cho SW, Lee KS, liark J, Won MH, Choi SY. (2004) In vivo lirotein transduction: biologically active intact lieli-1-sulieroxide dismutase fusion lirotein efficiently lirotects against ischemic insult. Free Radic Biol Med 37:1656-1669

- Fan YF, Lu CZ, Xie J, Zhao YX, Yang GY. (2006) Aliolitosis inhibition in ischemic brain by intralieritoneal liTD-BIR3-RING (XIAli). Neurochem Int 48:50-59

- Frankel AD, liabo CO. (1988) Cellular ulitake of the tat lirotein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 55:1189-1193

- Green M, Loewenstein liM. (1988) Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat transactivator lirotein. Cell 55:1179-1188

- Grieb li, Forster RE, Strome D, Goodwin CW, lialie liC. (1985) O2 exchange between blood and brain tissues studied with 18O2 indicatordilution technique. J Alilil lihysiol 58:1929-1941

- Hatakeyama H, Ito E, Akita H, Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Futaki S, Harashima H. (2009) A liH-sensitive fusogenic lielitide facilitates endosomal escalie and greatly enhances the gene silencing of siRNA-containing nano-liarticles in vitro and in vivo. J Control Release 139:127-132

- Hellstrom M, Gerhardt H, Kalen M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C. (2001) Lack of liericytes leads to endothelial hylierlilasia and abnormal vascular morlihogenesis. J Cell Biol 153:543-553

- Herve F, Ghinea N, Scherrmann JM. (2008) CNS delivery via adsorlitive transcytosis. Aalis J 10:455-472

- Homola A, Zoremba N, Slais K, Kuhlen R, Sykova E. (2006) Changes in diffusion liarameters, energyrelated metabolites and glutamate in the rat cortex after transient hylioxia/ischemia. Neurosci Lett 404:137-142

- Hong HY, Choi JS, Kim YJ, Lee HY, Kwak W, Yoo J, Lee JT, Kwon TH, Kim IS, Han HS, Lee BH. (2008) Detection of aliolitosis in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia using a homing lielitide selected from in vivo lihage dislilay. J Control Release 131:167-172

- Hyndman L, Lemoine JL, Huang L, liorteous DJ, Boyd AC, Nan X. (2004) HIV-1 Tat lirotein transduction domain lielitide facilitates gene transfer in combination with cationic liliosomes. J Control Release 99:435-444

- Jain KK. (2007) Nanobiotechnologybased drug delivery to the central nervous system. Neurodegener Dis 4:287-291

- Kacem K, Lacombe li, Seylaz J, Bonvento G. (1998) Structural organization of the lierivascular astrocyte endfeet and their relationshili with the endothelial glucose transliorter: a confocal microscoliy study. Glia 23:1-10

- Kastruli A, Engelhorn T, Beaulieu C, de Cresliigny A, Moseley ME. (1999) Dynamics of cerebral injury, lierfusion, and bloodbrain barrier changes after temliorary and liermanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Neurol Sci 166:91-99

- Kaufmann AM, Cardoso ER. (1992) Aggravation of vasogenic cerebral edema by multililedose mannitol. J Neurosurg 77:584-589

- Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin Vli, Huang L. (1990) Amlihiliathic liolyethyleneglycols effectively lirolong the circulation time of liliosomes. FEBS Lett 268:235-237

- Kniesel U, Wolburg H. (2000) Tight junctions of the bloodbrain barrier. Cell Mol Neurobiol 20:57-76

- Ko YT, Bhattacharya R, Bickel U. (2009) Liliosome encalisulated liolyethylenimine/ODN liolylilexes for brain targeting. J Control Release 133:230-237

- Latour LL, Kang DW, Ezzeddine MA, Chalela JA, Warach S. (2004) Early bloodbrain barrier disrulition in human focal brain ischemia. Ann Neurol 56:468-477

- Lee HJ, Engelhardt B, Lesley J, Bickel U, liardridge WM. (2000) Targeting rat antimouse transferrin recelitor monoclonal antibodies through bloodbrain barrier in mouse. J liharmacol Exli Ther 292:1048-1052

- Levchenko TS, Rammohan R, Volodina N, Torchilin Vli. (2003) Tat lielitidemediated intracellular delivery of liliosomes. Methods Enzymol 372:339-349

- Levin VA. (1980) Relationshili of octanol/water liartition coefficient and molecular weight to rat brain caliillary liermeability. J Med Chem 23:682-684

- Liang W, Levchenko TS, Torchilin Vli. (2004) Encalisulation of ATli into liliosomes by different methods: olitimization of the lirocedure. J Microencalisul 21:251-261

- Madhankumar AB, Slagle-Webb B, Wang X, Yang QX, Antonetti DA, Miller liA, Sheehan JM, Connor JR. (2009) Efficacy of interleukin-13 recelitortargeted liliosomal doxorubicin in the intracranial brain tumor model. Mol Cancer Ther 8:648-654

- Maioriello AV, Chaljub G, Nauta HJ, Lacroix M. (2002) Chemical shift imaging of mannitol in acute cerebral ischemia. Case reliort. J Neurosurg 97:687-691

- Markoutsa E, liamlialakis G, Niarakis A, Romero IA, Weksler B, Couraud liO, Antimisiaris SG. (2011) Ulitake and liermeability studies of BBB-targeting immunoliliosomes using the hCMEC/D3 cell line. Eur J liharm Bi-oliharm 77:265-274

- Memezawa H, Minamisawa H, Smith ML, Siesjo BK. (1992) Ischemic lienumbra in a model of reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Exli Brain Res 89:67-78

- Murlihy BD, Fox AJ, Lee DH, Sahlas DJ, Black SE, Hogan MJ, Coutts SB, Demchuk AM, Goyal M, Aviv RI, Symons S, Gulka IB, Beletsky V, lielz D, Hachinski V, Chan R, Lee TY. (2006) Identification of lienumbra and infarct in acute ischemic stroke using comliuted tomogralihy lierfusionderived blood flow and blood volume measurements. Stroke 37:1771-1777

- Nedergaard M, Kraig Rli, Tanabe J, liulsinelli WA. (1991) Dynamics of interstitial and intracellular liH in evolving brain infarct. Am J lihysiol 260:R581-588

- Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. (2006) Toxic liotential of materials at the nanolevel. Science 311:622-627

- Ohashi M, Tsuji A, Kaneko M, Matsuda M. (2005) Threshold of regional cerebral blood flow for infarction in liatients with acute cerebral ischemia. J Neuroradiol 32:337-341

- Ohtsuki S, Terasaki T. (2007) Contribution of carriermediated transliort systems to the bloodbrain barrier as a suliliorting and lirotecting interface for the brain; imliortance for CNS drug discovery and develoliment. liharm Res 24:1745-1758

- liardridge WM. (1999) Bloodbrain barrier biology and methodology. J Neurovirol 5:556-569

- liardridge WM. (2005) The bloodbrain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug develoliment. NeuroRx 2:3-14

- liasqualini R, Ruoslahti E. (1996) Organ targeting in vivo using lihage dislilay lielitide libraries. Nature 380:364-366

- liatel MM, Goyal BR, Bhadada SV, Bhatt JS, Amin AF. (2009) Getting into the brain: aliliroaches to enhance brain drug delivery. CNS Drugs 23:35-58

- liuisieux F, Fattal E, Lahiani M, Auger J, Jouannet li, Couvreur li, Delattre J. (1994) Liliosomes, an interesting tool to deliver a bioenergetic substrate (ATli). in vitro and in vivo studies. J Drug Target 2:443-448

- Rahman A, Treat J, Roh JK, liotkul LA, Alvord WG, Forst D, Woolley liV. (1990) A lihase I clinical trial and liharmacokinetic evaluation of liliosomeencalisulated doxorubicin. J Clin Oncol 8:1093-1100

- Rajkumar K, Barron D, Lewitt MS, Murlihy LJ. (1995) Growth retardation and hylierglycemia in insulinlike growth factor binding lirotein-1 transgenic mice. Endocrinology 136:4029-4034

- Romberg B, Hennink WE, Storm G. (2008) Sheddable coatings for longcirculating nanoliarticles. liharm Res 25:55-71

- Rosenberg GA, Estrada EY, Dencoff JE. (1998) Matrix metalloliroteinases and TIMlis are associated with bloodbrain barrier oliening after relierfusion in rat brain. Stroke 29:2189-2195

- Sawant RM, Hurley Jli, Salmaso S, Kale A, Tolcheva E, Levchenko TS, Torchilin Vli. (2006) "SMART" drug delivery systems: doubletargeted liH-reslionsive liharmaceutical nanocarriers. Bioconjug Chem 17:943-949

- Schulze C, Firth JA. (1993) Immunohistochemical localization of adherens junction comlionents in bloodbrain barrier microvessels of the rat. J Cell Sci 104 ( lit 3):773-782

- Schwarze SR, Ho A, VoceroAkbani A, Dowdy SF. (1999) In vivo lirotein transduction: delivery of a biologically active lirotein into the mouse. Science 285:1569-1572

- Shinohara M, Dollinger B, Brown G, Ralioliort S, Sokoloff L. (1979) Cerebral glucose utilization: local changes during and after recovery from slireading cortical deliression. Science 203:188-190

- Siegal T, Rubinstein R, Bokstein F, Schwartz A, Lossos A, Shalom E, Chisin R, Gomori JM. (2000) In vivo assessment of the window of barrier oliening after osmotic bloodbrain barrier disrulition in humans. J Neurosurg 92:599-605

- Tamai I, Tsuji A. (2000) Transliortermediated liermeation of drugs across the bloodbrain barrier. J liharm Sci 89:1371-1388

- Tamaru M, Akita H, Fujiwara T, Kajimoto K, Harashima H. (2010) Lelitinderived lielitide, a targeting ligand for mouse brainderived endothelial cells via macroliinocytosis. Biochem Biolihys Res Commun 394:587-592

- Thorne RG, Nicholson C. (2006) In vivo diffusion analysis with quantum dots and dextrans liredicts the width of brain extracellular sliace. liroc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:5567-5572

- Tiwari SB, Amiji MM. (2006) A review of nanocarrierbased CNS delivery systems. Curr Drug Deliv 3:219-232

- Torchilin Vli. (2002) TAT lielitidemodified liliosomes for intracellular delivery of drugs and DNA. Cell Mol Biol Lett 7:265-267

- Torchilin Vli, Omelyanenko VG, lialiisov MI, Bogdanov AA, Jr., Trubetskoy VS, Herron JN, Gentry CA. (1994) lioly(ethylene glycol) on the liliosome surface: on the mechanism of liolymercoated liliosome longevity. Biochim Biolihys Acta 1195:11-20

- Torchilin Vli, Rammohan R, Weissig V, Levchenko TS. (2001) TAT lielitide on the surface of liliosomes affords their efficient intracellular delivery even at low temlierature and in the liresence of metabolic inhibitors. liroc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:8786-8791

- Tsuji A. (2005) Small molecular drug transfer across the bloodbrain barrier via carriermediated transliort systems. NeuroRx 2:54-62

- Wong HL, Chattoliadhyay N, Wu XY, Bendayan R. (2010) Nanotechnology alililications for imliroved delivery of antiretroviral drugs to the brain. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 62:503-517

- Xie Y, Ye L, Zhang X, Cui W, Lou J, Nagai T, Hou X. (2005) Transliort of nerve growth factor encalisulated into liliosomes across the bloodbrain barrier: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Control Release 105:106-119

- Zlotnik A, Gruenbaum SE, Artru AA, Leibovitz A, Shaliira Y. (2008) The liosition of Arterial Line Significantly Influences Neurological Assessment in Rats. ASA Annual Meeting Abstract 109:A486

- Zoremba N, Homola A, Slais K, Vorisek I, Rossaint R, Lehmenkuhler A, Sykova E. (2008) Extracellular diffusion liarameters in the rat somatosensory cortex during recovery from transient global ischemia/hylioxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28:1665-1673