Research Article - Neuropsychiatry (2018) Volume 8, Issue 3

The Effect of Gerotranscendence Reminiscence Therapy among Institutionalized Elders: A Randomized Controlled Trial

- Corresponding Author:

- I-Chuan Li, PhD, RN

Institute of Community HealthCare, National Yang-Ming University, No. 155, Sec 2, Li-nong Street, Taipei, 11217, Taiwan

Tel: + (886-2)-2826-7176

Fax: + (886-2)-2826-7176

Abstract

ABSTRACT

Objective:

The meaning of life is important for older people to attain a high level of life satisfaction and face the future with hope by recognizing and integrating previous life experiences with current situation. Rediscovering the meaning of life is a crucial psychological objective. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of meaning of life after the application gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy among institutionalized elders.

Methods:

This study used an experimental, two-group, repeated measurement design. Using purposive sampling, 82 older adults were recruited from eight long-term care facilities in Taiwan. Subjects were randomly assigned to the intervention group or the comparison group. All the subjects were 65 years old or older and had normal cognitive functioning as measured by the Small Portable Mental Status Questionnaire. 41 subjects in the intervention group received the gerotranscendence reminiscence intervention once a week for eight weeks, with each session lasting 60 minutes. 41 subjects in the comparison group continued received regular activities provided by their institutions. The structured questionnaire included demographic items and a purpose in life test. The subjects completed each question at three different study time points: prior to receiving the intervention, right after the intervention, and six weeks after the intervention.

Results:

The results of the GEE analysis showed that there was a significant difference between the comparison and intervention groups in purpose in life scores one week after the completion of the intervention (β=14.07, p<0.001) and also after 6 weeks of the intervention (β=16.01, p<0.001). This indicated that the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy enhanced the belief that life has meaning and that the effects of the therapy lasted for at least six weeks.

Conclusions:

The results of this study support the conclusion that gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy can significantly increase the meaning of life for institutionalized elders.

Keywords

Gerotranscendence, Reminiscence therapy, Institutionalized elders, Meaning of life, Long- Term care

Introduction

Advancements in medical interventions and related technologies have led to significant increases in life expectancy in a wide range of developed countries, along with corresponding increases in the populations of elderly people in those nations. At the same time, this has resulted in increasing numbers of elderly people with disabilities who cannot take care of themselves and thus must reside in long-term care (LTC) institutions. In Taiwan, statistics from the Ministry of Health and Welfare indicate that the occupancy rate at LTC facilities increased from 72.9% in 2009 to 77.3% in 2015, with the rate expected to rise further in the future [1].

In addition to experiencing higher levels of disability and dependency than other age groups, older people are also more likely to experience hopelessness and depression toward the end of life [2]. However, researchers have found that the quest to find meaning in life can motivate an individual to overcome or transcend his or her own suffering [3]. Relatedly, perceptions regarding the meaning of life have been found to supply unique information about people’s quality of life (QoL) and are thought to be of particular importance as people age and, in some cases, move into nursing homes [4,5].

Some studies have supported that life is meaningful is important, especially among older people. For attaining a high level of life satisfaction and for facing the future with hope, in part because it allows people to recognize and integrate previous life experiences with their current situations. Meaning in life is an optimal defense for elderly people against the hopelessness, depression, and low self-esteem, as well as the chronic diseases and the effects of disabilities on their daily living activities, that are sometimes caused by or associated with aging [6,7]. Bohlmeijer et al. and Westerhof et al. have reported that one’s impressions regarding the meaning of life can mediate negative life events and depression [8,9]. As such, regarding life as meaningful or rediscovering a sense of meaning in life can be crucial for older people living in LTC institutions, so assisting these elderly residents in searching for and recognizing the meaning of life is of critical importance [10].

Many studies have provided reminiscence therapy to older people in order to decrease their depression and increase their sense of control over their current situations [11]. However, several studies that have examined the effects of reminiscence therapy on perceptions of meaning in life among institutionalized elders have found that reminiscence interventions are ineffective at facilitating changes in elders’ beliefs that life has meaning [12-14].

The concept and experience of gerotranscendence has been found to be a source of well-being among older people because it allows them to affirm their own existence and subsequently face their physical limitations, hardships, and pain with a positive attitude [15,16]. Gerotranscendence includes a psycho-social-spiritual component aimed at achieving personal maturity that is distinct from the more self-absorbed strivings for self-esteem and intimacy typical in earlier developmental phases [11,17]. Melin-Johansson et al. applied the concept of gerotranscendence in assisting a group of institutionalized elders in making positive adjustments in their lives [15]. The findings of that study demonstrated that these elders had improved knowledge of themselves, were less focused on changes to their body and appearance, experienced greater enjoyment in life, and exhibited less concern about social norms or material possessions than they did before taking part in the gerotranscendence intervention. Tornstam proposed that, in light of the theory of gerotranscendence, any reminiscence therapy should seek to emphasize, at least in part, that human understanding consists not only of an understanding of one’s self-identity, but also in the phenomenon of human persistence [16]. Gerotranscendence can eventually lead to spiritual reminiscence, a form of contemplation in which the elderly undergo a critical evaluation of their lives in order to gain new insights from their past that can help them to cope with the present and find meaning in the future [17]. Spiritual reminiscences, which can be infused in life-story work, can aid the elderly in finding new meaning and hope in life by reframing their life experiences, allowing them, in turn, to achieve new understanding, acceptance, and transcendence of said experiences [17].

Tornstam further suggested that the primary tasks for reminiscence therapy were as follows: to enable participants to arrive at novel ideas regarding time, space, life, and death; to help participants to know themselves through reflection and dialogue; to aid participants in relinquishing self-obsession; to encourage participants to positively examine their own past, present, and future; to help participants to escape time-restrictions and fear; to help participants to face death calmly; to spur participants to accept and appreciate life; to encourage participants to confront future life challenges in an active, positive manner; and to aid participants in apprehending and reflecting on their own lives [18]. In 2006, Wadensten conducted a qualitative focus group study aimed at enabling six female nursing home residents aged 68- 80 years old to understand the perspective of gerotranscendence, as well as to observe the changes in their own aging processes. Wadensten found that this intervention helped the seniors to view and evaluate other people, objects, and situations with a positive attitude, facilitated their reflections on their own lives, increased their self-knowledge, and empowered them with a sense of life cohesion. The study results further showed that the participants actively shared details of their own aging processes in the group, and that the perspective of gerotranscendence aided them in finding meaning in life, taking a more positive attitude toward aging, and feeling more at peace with their pasts.

At present, the only gerotranscendence study of older adults carried out in an Asian context was conducted by Wang et al. in Taiwan. In that study, 76 residents of LTC facilities were randomly assigned to either a gerotranscendenceintervention support group or a control group. Both groups participated in group activities, but only the support group engaged in the practical discussions on gerotranscendence, the self, and social activities [19]. They were encouraged to share their thoughts and experiences regarding every dimension of gerotranscendence, and to reflect and provide feedback on what they learned in the group sessions. The results showed that the residents in the support group were able to develop an attitude of gerotranscendence, and that their levels of life satisfaction improved significantly compared to those of the control group.

Because of cultural differences between Western and Eastern cultures, as well as potential differences in gerotranscendence perspectives between seniors from Northern and Southern Taiwan, one-to-one interviews were deemed appropriate. Moreover, one empirical study reported that perspectives on gerotranscendence were highly related to participants’ individual understandings of the meaning of life [20]. Few empirical studies conducted thus far, meanwhile, have applied the concept of gerotranscendence in reminiscence therapy and used perceptions regarding the meaning of life as an indicator of the effects of such gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine how institutionalized elders’ beliefs regarding the meaning of life were affected by the implementation of a reminiscence therapy intervention integrated with the theory of gerotranscendence.

Methods

This study used an experimental design. Specifically, a two-group, repeated measurement design was used to evaluate the effects of a gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy on the meaning of life beliefs of institutionalized elders.

▪ Participants

The researchers received a list of LTC facilities from the Department of Social Welfare of Taipei. By using purposive sampling, eight LTC facilities were selected and subsequently agreed to participate in the study. The criteria for the inclusion of subjects were as follows: (1) 65 years old or older; (2) able to verbally communicate in Mandarin or Taiwanese; and (3) normal cognitive functioning as measured by the Small Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) (normal ≥ 8). Elders were excluded if they had a mental illness diagnosis.

The sample size calculation for the study was based on Bohlmeijer et al. and Pinquart and Sorenson’s meta-analyses of the effects of reminiscence therapy, which revealed that meaning of life beliefs had a moderate effect [8,21]. Relatedly, the G*Power 3.1 software program was used to estimate the necessary sample size for the study. The sample size calculation (alpha = 0.05, power = 0.8, one-tailed, drop out percentage of twenty percent) estimated that 41 participants would be needed in each study group, namely, a gerotranscendence reminiscence intervention group and a comparison group; therefore, a total of 82 subjects were sought for participation in the study.

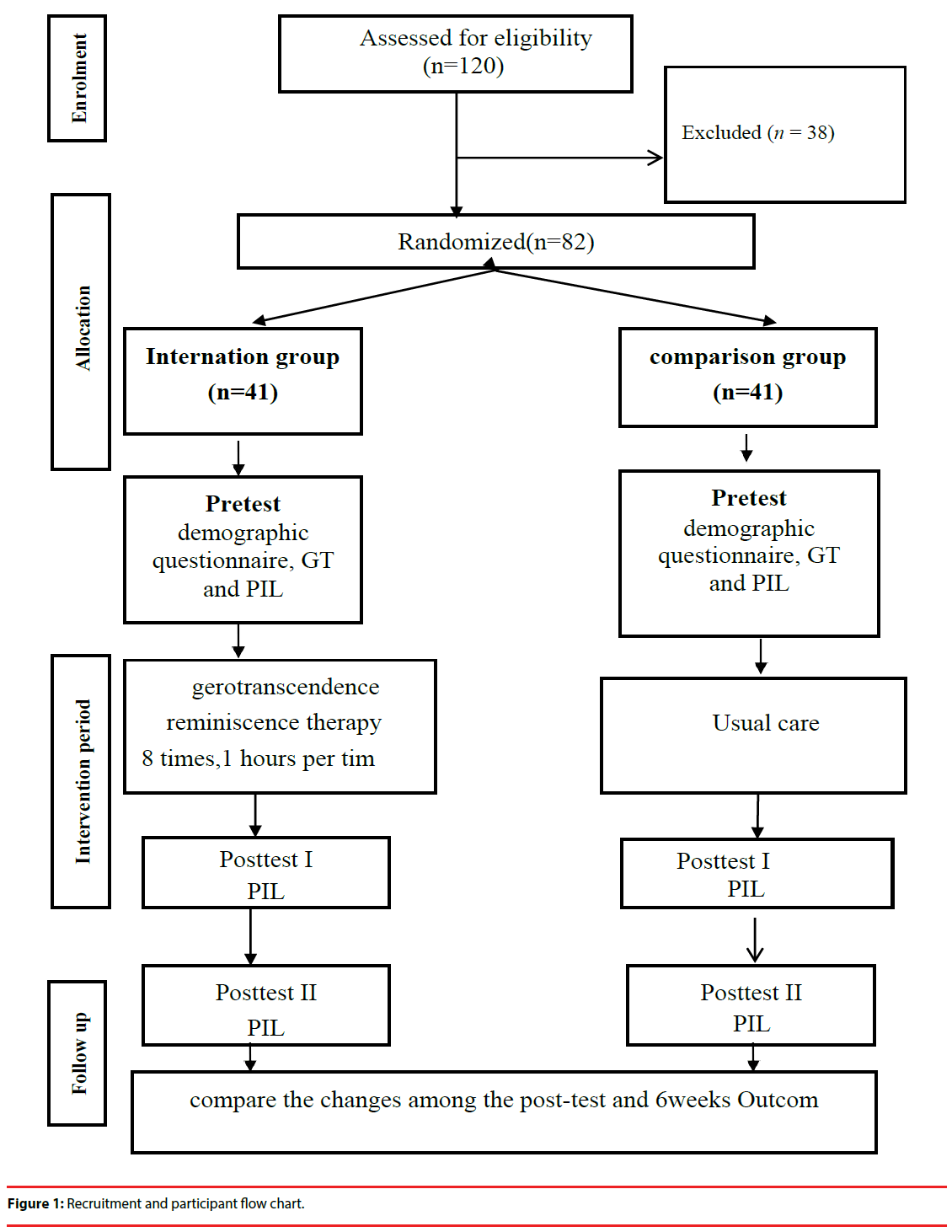

A total of 120 potential subjects met the inclusion criteria, out of which 82 did agree to participate. Then, random assignment of the willing participants to the intervention group and the comparison group was conducted by using a table list; the 41 even numbered subjects were assigned to the comparison group and the 41 odd numbered subjects were assigned to the intervention group. After six weeks of the intervention for those in the intervention group, 40 subjects remained in the intervention group, while all 41 members of the comparison group remained. The one person in the intervention group who withdrew did so because he moved to another city. The participants in the comparison group received their “usual care” without any additional intervention. “Usual care” meant that, as before the study, they could use or apply for all the available services in the area. A flow chart detailing the participants and key time points in this study is presented in Figure 1.

This research was carried out from Aug 2013 to July 2014 in Taiwan. Before data collection began, this study obtained Institutional Review Board approval from the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University (No.201307ES006). The eight selected LTC facilities also consented to participate, and the director of nursing for each facility provided a list of residents who met the study criteria. These residents were contacted individually and had the study explained to them, where after assigned written consent form was obtained from each resident who agreed to participate. To preserve their anonymity and confidentiality, only code numbers were used to identify the participants. The collected data and code books were secured with locks in separate places.

The subjects in both groups first completed a demographic questionnaire, as well as a gerotranscendence and purpose in life (PIL) assessment, immediately before the intervention began. They then completed the PIL assessment again one week after the completion of the intervention was completed and six weeks after the intervention was completed .Data were collected by the same researcher at each time point during one-on-one interviews.

▪ Measures

The measurement instruments in this study included a questionnaire regarding the subjects’ demographic data, a gerotranscendence scale, and a PIL scale for measuring the subjects’ perceptions regarding the meaning of life, which are described as follows:

▪ Purpose in life scale

The PIL scale was developed by Crumbaugh and Maholick [22]. They designed the scale items mainly to quantify the existential concept of meaning in life in relation to existential frustration or existential vacuum. The PIL test consists of 20 items, each to be responded to by the participant by indicating either personal agreement or disagreement on a seven-point scale. The total score for the test thus ranges from 20 to 140.The scores can be interpreted to reflect differing levels of belief with regard to how meaningful life is. The lower an individual’s score, the less meaningful he or she perceives life to be. Jonsen et al. applied this scale to measure the meaning of life perceptions of the elderly and found it to have good reliability based on a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.83 [23]. This study used the Chinese version of the scale made by Chen [24]. The Chinese PIL contains 16 items covering five factors: personal sense of worth, sense of fulfillment, self-esteem, sense of autonomy, and sense of achievement. This study invited seven experts in geriatrics and long-term care to evaluate the validity of this Chinese version of the PIL test in terms of its appropriateness and clarity, and the content validity index (CVI) was established to be 0.80, indicating that this Chinese version of the scale is appropriate. The experts recommended that three more questions be added, yielding a total of 19 questions in the modified scale. The items within the Chinese scale were scored on a 4-point scale. The scores for the scale ranged from 19 to 76; the higher the score, the more meaningful the respondent perceived life to be.

▪ Gerotranscendence scale

The 10-item Gerotranscendence Scale [17], translated by Wang [19], was used to measure the subjects’ gerotranscendence perspectives. The 10-item scale includes five items regarding cosmic transcendence, two items regarding coherence, and three items regarding solitude. Each item is measured using a Likert scale, with the responses ‘‘Never,’’ ‘‘Rarely,’’ ‘‘Sometimes,’’ and ‘‘Usually’’ being scored as 1, 2, 3, and 4 points, respectively. Total scores thus ranged from 10 to 40 points, with a higher score indicating a higher level of gerotranscendence (GT) perspective. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the internal consistency reliability of the Chinese version was previously found to be 0.56 (Wang, 2011). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the internal consistency reliability was 0.76.

▪ Intervention

The intervention utilized in this study consisted of a newly developed program based on the theory of gerotranscendence by Tornstam [17], with sessions involving individual reminiscences serving as the intervention form. More specifically, the intervention group received the reminiscence intervention, including application of the gerotranscendence concept, on a weekly basis for eight weeks, with each session lasting for 60 minutes. At the commencement of the study, all of the participants were interviewed on a one-to-one basis; the interview began with the interviewer establishing trust and demonstrating empathy in order to encourage the elderly adults to share their feelings and experiences. The sessions concentrated on a different topic each week. The eight topics of the sessions were as follows: (1) “My Older Life”; (2) “Leading Man or Lady”; (3) “Let’s Rock! Grandpa and Grandma Take on Life”; (4) “A Spiritual Journey through Religion and Folk Culture”; (5) “The Joy of My Past Work”; (6) “Love and Compassion in the World”; (7) “The Ups and Downs of My Current Life Stage”; and (8) “Past and Present” (Table 1).

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| My Older Years | Sought to understand aging and how physical functions change. Changes in physical function and the resulting limitations—and how to adjust in response to these limitations—were viewed from the perspective of transcendence. |

| Leading Man or Lady | Focused on searching for the meaning of life in personal experiences. Meaning of life is primarily found through creative and experiential values. |

| Let’s Rock! Grandpa and Grandma Take on Life | The subjects were guided to share stories about the people, events, and objects that made them happy or satisfied and to rediscover their past interests. |

| A Spiritual Journey through Religion and Folk Culture | Helped the subjects clarify their opinions regarding religion and what religion meant to them from the perspective of cosmic transcendence. |

| The Joy of My Past Work | Looked for the meaning and importance of past work from the perspective of interpersonal transcendence in order to determine the meaning of life by addressing career development. |

| Love and Compassion in the World | Looked for the meaning of family and friendships from the perspective of interpersonal transcendence in order to determine the meaning of life with empirical and creative value. |

| The Ups and Downs of My Current Life Stage | Recalled the lives of the residents, guiding them in reviewing their past, present, and future. Also guided them in the reinterpretation and acceptance of past mistakes that they were unable to get out of their mind. |

| Past and Present | Shared perspectives regarding the end of life and the fear of death, as well as the understanding that death is a natural part of human life. |

Table 1: Descriptions of gerotranscendence reminiscence activities.

▪ Data analysis

SPSS21.0 for Windows software was used for the data analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the sample. The changes in meaning of life perceptions over the different time points were analyzed using the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach. Statistics significance was set at the conventional p<0.05 level (two-tailed).

Results

▪ Participant demographics

The sample demographics are listed in Table 2. Sixty-six percent of the LTC residents were female, and the mean age of all the participants was 80.57(SD 7.87). More than half (63.4%)of the residents had lost their spouses, and 43.9 % had a low educational level ranging from basic literacy to the completion of elementary school. 35.4%of the residents were Buddhist, and 40.2 % had lived alone before they were admitted to the facility. The mean length of institutionalized care was 31.37 (SD 50.80) months. The average number of chronic illnesses was 2.68, and the subjects were taking an average of 7 (SD3) medications. The mean activities of daily living (ADL) score was 68 (SD 25.88), a score which would be classified as “moderately dependent.” Before the intervention, there were no significant differences between the two groups for the following variables: gender, marital status, education level, self-perceived economic status, ADL score, and the number of chronic medical illnesses (Table 2). However, the two groups did have significant differences in terms of ethnicity before the intervention (P=0.02). Therefore, GEE analysis was used in this study to remove any effects of such differences when determining the impact of the intervention.

| Total (n=82) | Intervention (n=41) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean(SD) | N% | Mean(SD) | N% | Comparison (n=41) | N% | t/x | p |

| Age | 80.57(7.87) | 81.06(8.06) | 80.07(7.75) | 0.57 | 0.57 | |||

| Gender | 0.22 | 0.64 | ||||||

| Male | 28(34.1) | 13(31.7) | 15(36.6) | |||||

| Female | 54(65.9) | 28(68.3) | 26(63.4) | |||||

| Ethnicity | 5.89 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Taiwanese | 58(70.7) | 24(58.5) | 34(82.9) | |||||

| Mainland | 24(29.3) | 17(41.5) | 7(17.1) | |||||

| Education level | 5.49 | 0.37 | ||||||

| Illiterate | 16(19.5) | 7(17.1) | 9(22.0) | |||||

| Literate & | 36(43.9) | 19(46.3) | 17(41.5) | |||||

| Elementary | ||||||||

| Junior high school | 8(9.8) | 2(4.9) | 6(14.6) | |||||

| High school | 12(14.6) | 6(14.6) | 6(14.6) | |||||

| College and above | 10(12.2) | 7(17.1) | 3(7.3) | |||||

| Marital status | 4.59 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Married | 13(15.9) | 3(7.3) | 10(24.4) | |||||

| Never married | 6(7.3) | 3(7.3) | 3(7.3) | |||||

| Divorced/separated | 11(13.4) | 6(14.6) | 5(12.2) | |||||

| Widowed/widower | 52(63.4) | 29(70.7) | 23(56.1) | |||||

| Religious belief | 4.42 | 0.32 | ||||||

| None | 16(19.5) | 9(22.0) | 7(17.1) | |||||

| Taoism/traditional | 26(31.7) | 10(24.4) | 16(39.0) | |||||

| Buddhism | 29(35.4) | 14(34.1) | 15(36.6) | |||||

| Christian | 11(13.4) | 8(19.5) | 3(7.3) | |||||

| /Catholicism | ||||||||

| Self-perceived | 1.27 | 0.53 | ||||||

| economic status | ||||||||

| Insufficient income | 9(11.0) | 4(9.8) | 5(12.2) | |||||

| Balanced income | 57(69.5) | 27(65.9) | 30(73.2) | |||||

| Sufficient income | 16(19.5) | 10(24.4) | 6(14.6) | |||||

| Duration of | 31.37(50.8) | 30.85(49.2) | 31.88(52.9) | -0.09 | 0.93 | |||

| institutionalization | ||||||||

| Visitation | 3.03 | 0.7 | ||||||

| frequency | ||||||||

| None | 1(1.2) | 0(0.0) | 1(2.4) | |||||

| Once a day | 6(7.3) | 2(4.9) | 4(9.8) | |||||

| Once a week | 37(45.1) | 19(46.3) | 18(43.9) | |||||

| Every two weeks | 8(9.8) | 5(12.2) | 3(7.3) | |||||

| Monthly | 6(7.3) | 4(9.8) | 2(4.9) | |||||

| No answer | 24(29.3) | 11(26.8) | 13(31.7) | |||||

| ADL | 68.00(25.88) | 68.54(25.50) | 67.44(26.56) | 0.19 | 0.85 | |||

| GT | 24.88(3.81) | 26.78(3.55) | 22.98(3.05) | 5.21 | <0.001 | |||

| Total number of chronic diseases | 2.68 (1.18) | 2.76 (1.24) | 2.61 (1.12) | 0.56 | 0.58 | |||

| Number of | 0.54 | 0.76 | ||||||

| diagnosed chronic diseases | ||||||||

| 01-Feb | 40 (48.8) | 19 (46.3) | 21(51.2) | |||||

| 03-Apr | 37 (45.1) | 20 (48.8) | 17 (41.5) | |||||

| 05-Jun | 5 ( 6.1) | 2 ( 4.9) | 3 (7.3) | |||||

| Total number of | 7.23 (3.15) | 6.59 (2.79) | 7.88 (3.38) | -1.89 | 0.06 | |||

| medications prescribed | ||||||||

| 2.18 | 0.34 | |||||||

| 01-May | 24 (29.3) | 15 (36.6) | 9 (22.0) | |||||

| 06-Oct | 46 (56.1) | 21(51.2) | 25 (61.0) | |||||

| ≧11 | 12 (14.6) | 5(12.2) | 7 (17.1) | |||||

Table 2: Demographic characteristics and homogeneity test results (n=82).

▪ Effects of gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy

This study used the PIL score and its subscales as outcome indicators. It shows the pattern of results for each outcome. Table 3 illustrates the results following the GEE analysis adjustments for the effects of the two covariates.

| Intervention group (n=41) | Comparison group | (n=41) | Compare differences between groups (n=82) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test1 | Post-test 2 | Pre-test | Post-test1 | Post-test 2 | ||||||||||

| Variable | Mean | Mean | Mean | t1 | t2 | t3 | Mean | Mean | Mean | t1 | t2 | t3 | t1a | t2a | t3a |

| (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | ||||||||||

| Meaning of life | 45.44 | 55.98 | 56.53 | 13.14*** | 11.20*** | 1.24 | 40.51 | 36.98 | 35.27 | -9.24*** | -11.17*** | -6.10*** | 15.84*** | 14.97*** | 4.95** |

| 10.59 | 7.84 | 8.45 | 7.90 | 7.60 | 7.72 | ||||||||||

| Sense of worth | 21.32 | 25.73 | 25.88 | 10.43*** | 9.34*** | 0.33 | 19.10 | 17.32 | 16.49 | -7.17*** | -8.75*** | -5.19*** | 12.62*** | 12.59*** | 3.97** |

| 5.38 | 3.50 | 3.70 | 3.76 | 4.08 | 4.04 | ||||||||||

| Fulfillment | 7.98 | 10.32 | 10.50 | 9.33*** | 8.20*** | 1.23 | 6.80 | 6.15 | 5.90 | -3.97*** | -4.05*** | -1.76 | 9.97*** | 9.05*** | 2.13* |

| 2.39 | 2.26 | 2.40 | 2.08 | 1.64 | 1.60 | ||||||||||

| Sense of direction | 10.15 | 12.37 | 12.45 | 7.98*** | 7.88*** | 0.85 | 9.68 | 8.88 | 8.44 | -4.89*** | -7.02*** | -3.78** | 9.35*** | 10.39*** | 3.26** |

| 2.32 | 1.44 | 1.45 | 2.18 | 2.15 | 2.29 | ||||||||||

| Sense of autonomy | 6.00 | 7.56 | 7.70 | 10.83*** | 8.47*** | 1.07 | 4.93 | 4.63 | 4.44 | -3.11** | -4.01*** | -2.45* | 10.77*** | 9.31*** | 2.41* |

| 2.12 | 1.86 | 1.92 | 1.56 | 1.43 | 1.34 | ||||||||||

『t』paired-t test: Comparison of the group at different times, t1: post-test 1 and pre-test comparison; t2: post-test 2 and pre-test comparison; t3: post-test 2 and post-test 1 comparison.

『t』independent sample t-test: Compare differences between groups at different times; t1a: post-test 1 and pre-test comparison; t2a: post-test 2

and pre-test comparison; t3a: post-test 2 and post-test 1 comparison.

Table 3: Effects of gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy at one week and at six weeks after completion of the intervention (n=82).

▪ Comparison of changes in the PIL scores

The GEE approach was used to assess the effect of the intervention on the PIL scores for the two groups by comparing the scores before and after the intervention. The results of the GEE analysis showed that there was a significant difference between the comparison and intervention groups in PIL scores one week after the completion of the intervention (β=14.07, p<0.001) and also after 6 weeks of the intervention (β=16.01, p<0.001) (Table 3). This indicated that the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy enhanced the belief that life has meaning among the residents in the intervention group and that the effects of the therapy lasted for at least six weeks.

▪ Comparison of the changes in the scores for the meaning of life subscales regarding personal esteem, fulfillment, direction, and sense of worth

With the ethnicity variable controlled for, the GEE results showed statistically significant differences in the intervention group in terms of sense of worth after the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy, and at six weeks after the completion of the intervention (β=6.20 , p<0.001; β=7.01, p<0.001) (Table 3). This shows that, among institutionalized elders, the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy can increase the sense of self-worth drawn from the perception that life has meaning for a relatively long length of time.

The results of the GEE analysis also showed that there was a significant difference between the comparison group and the intervention group in terms of fulfillment (β=3.30, p<0.001; β=3.36, p<0.001), both at one week after completion of the intervention and at six weeks after completion of the intervention (Table 4). This shows that the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy had long-term effects on the sense of fulfillment aspect of the meaning of life as perceived by the institutionalized elders.

| Meaning of life | Sense of worth | Fulfillment | Sense of | direction | Sense of autonomy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P |

| Intercept | 18.14 | 0.002 | 7.89 | 0.006 | 2.11 | 0.145 | 5.57 | <0.001 | 2.36 | 0.059 |

| Ethnicity(Taiwanese/ Mainland) | 2.58 | 0.169 | 1.11 | 0.222 | 0.35 | 0.455 | 0.18 | 0.684 | 0.96 | 0.017 |

| GT | 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.48 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.005 | 0.11 | 0.050 |

| Group(Intervention/ Comparison) | 0.67 | 0.737 | 0.12 | 0.899 | 0.32 | 0.525 | -0.30 | 0.641 | 0.44 | 0.294 |

| Time1(post-test 1/pre-test1) | -3.54 | <0.001 | -1.78 | <0.001 | -0.66 | 0.002 | -0.81 | 0.001 | - 0.30 | 0.020 |

| Time2(post-test /pre-test) | -5.24 | <0.001 | -2.61 | <0.001 | -0.90 | <0.001 | -1.24 | <0.001 | - 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Group × Time1 | 14.07 | <0.001 | 6.20 | <0.001 | 3.30 | <0.001 | 3.02 | <0.001 | 2.13 | <0.001 |

| Group × Time2 | 16.01 | <0.001 | 7.01 | <0.001 | 3.36 | <0.001 | 3.54 | <0.001 | 1.85 | <0.001 |

Table 4: GEE analysis results for gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy.

The results of the GEE analysis likewise showed a significant difference between the comparison group and the intervention group in terms of sense of direction (β=3.02, p<0.001; β=3.53, p<0.001), both at one week after completion of the intervention and at six weeks after completion of the intervention (Table 4). This shows that the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy had long-term effects on the sense of direction aspect of the meaning of life as perceived by the institutionalized elders.

The results of the GEE analysis also showed that there was a significant difference between the comparison group and intervention group in terms of sense of autonomy (β=1.85, p<0.001; β=2.13, p<0.001), both at one week after completion of the intervention and at six weeks after completion of the intervention (Table 4). This shows that the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy had long-term effects on the autonomy aspect of the meaning of life as perceived by the institutionalized elders.

Discussion

In this study, gerotranscendence reminiscing provided the subjects with a path for reorganizing their life experiences, allowing them to transform their views with regard to accepting past negative experiences. They gained new insights into meaningful life experiences, adjusted their thinking in a way that made their self-identities more positive, and maintained goals and hopes for the future by integrating their life experiences. Moreover, the elderly participants were also able to face death with a positive attitude, perceive the cohesiveness and meaningfulness of life, and enhance their sense of self-worth.

In this study, the topics used in the reminiscence therapy were drawn from the theory of gerotranscendence [17] in order to explore three dimensions: the cosmic dimension, the self, and social and personal relationships. The following sections discuss the effects of gerotranscendence reminiscing in terms of the sense of self-worth, sense of fulfillment, sense of direction, and sense of autonomy.

▪ Sense of self-worth in the meaningfulness of life

In this study, the activity for the reminiscing topic “Leading Man or Lady” asked the subjects to recall the significance of their roles and affirm these roles in each stage of their lives. The subjects recalled their achievements and emotionally positive memories and felt a sense of accomplishment and glory about their past. They primarily found meaning and value in their lives through focusing on their children or grandchildren and their own contributions to and achievements in their home life. Liao has stated that self-worth is expressed through personal work performance as well as through contributions to and the achievements of the family [25]. These expressions of self-worth thus allow individuals to affirm their life value, and achieving ego-integrity enables them to live a more harmonious life

▪ Sense of personal fulfillment in the meaningfulness of life

In this study, during the activity for the reminiscing topic “Let’s Rock! Grandpa and Grandma Take on Life,” the subjects rediscovered their younger selves and learned to enjoy the many facets of life, which in turn led them to feel that life was no longer boring and monotonous. The subjects found a greater capacity to see cheerful and pleasant aspects in the various surroundings, people, events, and objects they saw in their daily lives. They appreciated that many things in nature is alive and should be cherished, and through this appreciation, they found life to be pleasurable.

Frankl proposed that individuals can discover meaning in life by understanding the truth, goodness, and beauty of the things and events in their lives and through experiencing love [26]. In the present study, subjects experienced the beauty of nature, the beauty of a rich life, the enjoyment of pleasure, and the enjoyment of exploring the meaning of life. They found meaning in their lives through a cosmic transcendence perspective and through the pleasures of life. Our results were similar to those reported by Lee et al. regarding the meaning in life found by elderly adults in the topic “Enjoying a Dance with Nature.” Lee et al. regarded the longing for nature among elderly adults as a spiritual need that was satisfied, for those who participated in their study, through their engagement with the topic [27].

▪ Sense of direction in the meaningfulness of life

In this study, the reminiscing topic “A Spiritual Journey through Religion and Folk Culture” helped the subjects clarify their opinions regarding religion and what religion meant to them from the perspective of cosmic transcendence. By recalling the frustrations, suffering, and illnesses they had experienced in their lives, the subjects found that religious beliefs and rituals helped them to better bear the burdens imposed by any unavoidable suffering and rendered such experiences meaningful. The reminiscing topic “Past and Present” focused on viewing death from the perspective of cosmic transcendence, through which the subjects found meaning in life according to the attitudes they adopted toward death. These results are similar to those reported by Tornstam and Wadensten, who found that elderly adults were capable of recognizing the wonders of the universe and understanding that life is not eternal; thus, they were less afraid of death and believed that it is a natural phenomenon [18,28]. Chong found that the pursuit of religious faith can provide a sense of direction in life, spiritual enrichment, mental stability [29], and mental comfort, enabling individuals to adapt to changes in reality. When faith develops as a result of life experiences, religion can become the ultimate inner guide in life, providing direction to life and mental comfort that enables adaptation to changes in reality.

▪ Sense of autonomy in the meaningfulness of life

In this study, the goals of the reminiscing topics “My Older Years” and “The Ups and Downs of My Current Life Stage” were to understand aging and how physical functions change. During the activity period, we guided the subjects to transcend their limitations. By re-examining themselves to find a positive perspective regarding their obstacles and by transforming their views to identify suitable coping methods, they gradually began taking control of their lives, despite living in an institution. In their current situation, their ultimate goals were developing their interests and engaging in physical exercise. They pursued these goals earnestly and actively as a means of maintaining their autonomy.

In this study, we tracked the results of the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy at six weeks of the intervention activities. We found that the effects persisted for six weeks, at six weeks after the completion of the intervention, subjects continued to feel a significant increase in the perceived meaningfulness of their lives. Lee asserted that an understanding of life situations and events is the source of meaning in life for older people and produces the courage to face life [30]. Thus, the interpretation of what constitutes a meaningful life is closely tied to an individual’s current situation and environment.

Though the outcomes of the present study are encouraging, one of the study’s limitations was that the outcome measures depended solely on self-reporting. A more qualitative assessment could potentially provide a more comprehensive picture of the effect of gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy among institutionalized elders. Furthermore, the effects seen may have been the result of participating in the discussion group rather than the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy itself. In the present study, the immediate effects after two months of intervention were assessed and the effects were then tracked for another six weeks thereafter; this was another limitation. We recommend that future studies employ a longitudinal approach with tracking at 12, 18, and 24 weeks after completion of the intervention to highlight the long-term effects of the intervention In addition, changes in the residents’ situations can be assessed and the duration of the intervention effectiveness can be analyzed to determine how often and for how long the intervention should be provided.

Limitations

Though the study outcomes are encouraging, the limitation was that the outcome measures depended solely on self-reporting. A more qualitative assessment can provide a more comprehensive picture of the effect of gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy among institutionalized elders. Furthermore, the effectiveness may be the result of participating in the discussion group rather than the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy itself. In the present study, the immediate effects after two months of intervention were assessed and the effects were then tracked for another six weeks thereafter; this is another limitation. We recommend that future studies employ a longitudinal approach with tracking at 12, 18, and 24 weeks to highlight the long-term effects of the intervention. In addition, changes in the residents’ situations can be assessed and the duration of the intervention effectiveness can be analyzed to determine the intervention frequency to be adopted.

Conclusion

Using an experimental design, this study aimed to examine the effects of gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy on perceptions regarding the meaningfulness among institutionalized elders. The subjects in the intervention group received gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy once a week for eight weeks, with each session lasting for 60 minutes.The PIL scale was used to compare changes to the subjects’ perceptions regarding the meaning of life resulting from the intervention, as well any differences between the intervention group and the comparison group before and after the intervention.The results of this study show that a gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy intervention can effectively increase the perception regarding the meaningfulness of life among institutionalized residents and can be used to explore various indicators such as spiritual health, hope, and anxiety about death. The results of this study support the conclusion that gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy can significantly increase the meaning of life for institutionalized elders.

Therefore, it is important to apply the gerotranscendence reminiscence therapy as a regular service in such long-term care facilities in order to increase the meaning of life for older people in these institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the 82 residents of the LTC facilities who participated in this study. We are also grateful to Mr. Chen for agreeing to provide the questionnaires for this study and to all the experts who participated in the research for their guidance and advice.

References

- Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (2016).

- Syed Elias SE, Neville C, Scott T. The effectiveness of group reminiscence therapy for loneliness, anxiety and depression in older adults in long-term care: a systematic review. Geriatr. Nurs 6(5), 372-80 (2015).

- Tsai CS. Reconstructing Life Meaning of the Elderly with Cancer in One Public Residential Home[dissertation].Taipei: Shih Chien University; (2014).

- Krause N. Evaluating the stress-buffering function of meaning in life among older people.J .Aging. Health19(5), 792-812 (2007).

- Wadensten B. The theory of gerotanscendence as applied to gerontological nursing-PartI. Int. J. Older. People. Nurs 2(1), 289-294 (2007).

- Moore SL, Metcalf B, Schow E. The quest for meaning in aging. Geriatric. Nursing 27(5), 293-299 (2006).

- Evangelista LS, Doering L, Dracup K. Meaning and life purpose: The perspectives of post-transplant women. Heart. And. Lung 32(1), 250-257 (2003).

- Bohlmeijer E, Westerhof GJ, Emmerik-de Jong M. The effects of a new narrative life-review intervention for improving meaning in life in older adults: Results of a pilot project. Aging. Ment. Health12(1), 639-646 (2008).

- Westerhof GJ, Bohlemijer E, Webster JD. Reminiscence and mental health:a review of recent progress in theory, research and interventions. Aging. Soc 30(1), 697-721 (2010).

- Yang HH. A Study on Meaning of Life and Death Anxiety of Older Persons in Long-Term Care Facilities -A Case Study of Kaohsiung and Pingtung Region [dissertation]. Chhiayi : Nanhua University ; (2010).

- Wadensten B, Carlsson M. Theory-driven guidelines for practical care of older people, based on the theory of gerotranscendence. J. Adv. Nurs41(5), 462-470 (2003).

- LinY.C, Dai YZ, Hwang SLi. The Effect of Reminiscence on the Elderly Population: A Systematic. Public. Health. Nursing 20(4), 297-306 (2003).

- Hsieh HF, Wang JJ. Effect of reminiscence therapy on depression in older adults a systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud40(1), 335-345 (2003).

- Pinquart M, Forstmeier S. Effects of reminiscence intervention on psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Aging. Ment. Health 16(5), 541-558 (2012).

- Melin-Johansson C. Reflections of older people living in nursing homes. Nurs. Older. People 26(1), 33-39 (2014).

- Tornstam, L. Gerotranscendence and the functions of reminiscence. J. Aging. Ident 4(3), 155-166 (1999).

- Tornstam L. Caring for the elderly.Introducing the theory of gerotranscendence as a supplementary fram of reference for care of elderly. Scand. J. Caring. Sci 10(1), 144-150 (1996).

- Wadensten B. Introducing older people to the theory of gerotranscendence - discussion group about ageing for older women. J. Adv. Nurs52 (4), 381-388 (2005).

- Wang JJ. A structural model of the bio-psycho-socio-spiritual factors influencing the development towards gerotranscendence in a sample of institutionalized elders. J. Adv. Nurs 67(12), 2628-2636 (2011).

- Braam AW, Bramsen I, VanTilburg , et al. Cosmic transcendence and framework of meaning in life: patterns among older adults in the Netherlands. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci 61(3), 121-128 (2006).

- Pinquart M, Sorenson S. How effective are psychotherapeutic and other psychosocial intervention with older adults? A meta-analysis. J. Aging. Ment. Health7(1), 207-243 (2001).

- Crumbaugh JC, Maholick LT. An experimental study in existentialism:The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of Noogenic Neurosis. J. Clin .Psychol20(1), 200-2071964).

- Jonse’n E, Fagerstro¨m L, Lundman B, et al. Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Purpose in Life scale. Scand. J .Caring. Sci24(1), 41-48 (2010).

- Cheng YG. A Study on the Relevant Factors of Psychological Adaptation of Retired Old Citizens and the Effect of Structured Consciousness Group [dissertation]. Taipei: National Taiwan Nornal University (1986).

- Liao LL. Exploring the Meaning of Life from Elder Based on their Suffering Experience [dissertation] .Taipei : Fu Jen Catholic University ( 2011).

- Frankl VE. The Will to Meaning:Foundations and logotherapy. New York:VintaseBroks,(1986).

- Lee TF, Wu LF, Su HC. Exploring to Life-Meaning of Elderly through Spiritual Reminiscence. Taiwan. Elderly. Services. Management. Journal 2(1), 83-112 (2013).

- Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence: The contemplative dimension of aging. J. Aging. Stud11(2), 143-154 (1997).

- Chong CY. Construction of Meaning of Life and Actualization in Middle-aged Terminally-ill Cancer Patients [dissertation]. Changhua: National Changhua University of Education; (2008).

- Lee WL. Meaning in life of elderly nursing home residents[dissertation]. Taichung: China Medical University; (2008).