Research Article - Diabetes Management (2023) Volume 13, Issue 3

The experience of the Italian diabetes community on violence in clinical care services from a gender perspective: A questionnaire survey

- Corresponding Author:

- Chiara Giuliani

Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine

University of Messina, Messina, Italy

E-mail: chiara.giul@gmail.com

Received: 08-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. FMDM-23-94859; Editor assigned: 10-Apr-2023, PreQC No. FMDM-23-94859 (PQ); Reviewed: 25-Apr-2023, QC No. FMDM-23-94859; Revised: 04-May-2023, Manuscript No. FMDM-23-94859 (R); Published: 11-May-2023, DOI: 10.37532/1758-1907.2023.13(3).466-473

Abstract

Keywords

■violence in the workplace

■ diabetology

■ age

■ gender

■ program of violence prevention

Introduction

“Violence in the workplace” as defined by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health-USA (NIOSH), is “any aggression, threatening behavior, verbal or physical abuse that occurs in the workplace” [1].

The phenomenon of “violence in the workplace” (WPV) is constantly increasing and the healthcare sector is one of the hardest hit [2]. Given the prevalence, WPV cannot be considered as a marginal phenomenon but rather a daily event that can be found in many countries both, European and non-European, as confirmed by numerous international meta-analyzes and scoping reviews [3-6]. A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis highlighted how WPV phenomena have increased also during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an average prevalence of 68% against physicians and 47% against nurses, with a higher incidence in America compared to Asia, probably due to the different context and the cultural characteristics of these communities populations [7]. The growing interest in the phenomenon was also confirmed by a bibliometric analysis which highlighted how, from 1992 to 2019, the literature published on violence in health care workers has steadily grown from year to year, both in the number of documents and in the number of citations, demonstrating the increased concern about this public health issue [8]. Among risk factors for violence in the context of clinics and hospitals it is possible to identify exogenous factors, not directly preventable and/or controllable by design managers (e.g. subjective characteristics of the user, abuse of drugs or alcohol, certain psychotic diagnoses), but also structural and organizational factors that can facilitate the occurrence of aggressive phenomena and on which it is possible to intervene according to a preventive logic (long waits for service, working alone, poor environmental design, inadequate security) [1].

▪ Purpose of the survey

The aim of this survey was to quantify the dimension of the phenomenon of violence in the workplace, more specifically among healthcare professionals in diabetes centers, and how much this phenomenon can be related to any deficiencies in Risk Assessments (RAs) in the workplace.

Methodology

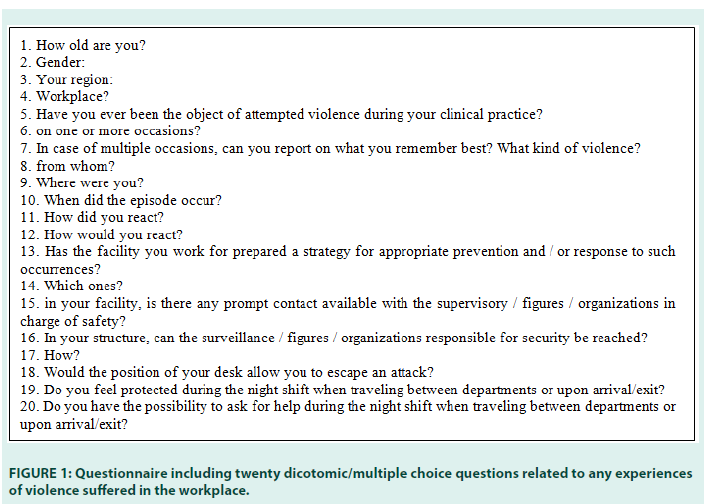

From the beginning of May to the end of June 2022 the ‘Gender Medicine’ board members, a strategic group of AMD, sent by E-mail to the society members an anonymous selfadministered questionnaire, which included twenty dicotomic/multiple choice questions, related to any experiences of violence suffered in the workplace (FIGURE 1).

The first part covered structural questions, to collect the respondents’ basic demographic data, with the aim to perform a subsequent analysis on whether differences in physicians sex lead to different level and/or type of violence. The questionnaire was easy and quick to fill out, to encourage participation in the initiative.

The answers received, through a pre-established automatic detection system, were automatically tabulated and analyzed at the end of the two months, chosen as time interval for data collection.

▪ Sample size calculation and statistics

Sample size estimation was based on the average prevalent violence recurrence reported in healthworker places ranging from 8% to the 38%, in two thirds of cases against nurses;

➢ With a minimum prevalence of 12,6% among the medical population, a statistical power of 80% and an estimated α error of 0.05, at least 113 physicians needed to be interviewed.

➢ Sample size analysis was carried out using clincalc.com.

➢ All continuous data are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables with Gaussian distribution, as median and range (min-max) for continuous variables with non-Gaussian distribution and as a frequency percentage for categorical variables.

➢ Categorical data are expressed as absolute and percentage of observations. Associations between the questionnaire items investigating the participants’ main demographic characteristics and the experience of violence were assessed using the chi-square test or the “T-test or Mann- Whitney Test” when applicable. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

➢ Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

▪ Informed consent

All the healthcare workers who participated in the survey gave online informed consent.

FIGURE 1 Questionnaire including twenty dicotomic/multiple choice questions related to any experiences of violence suffered in the workplace.

Results

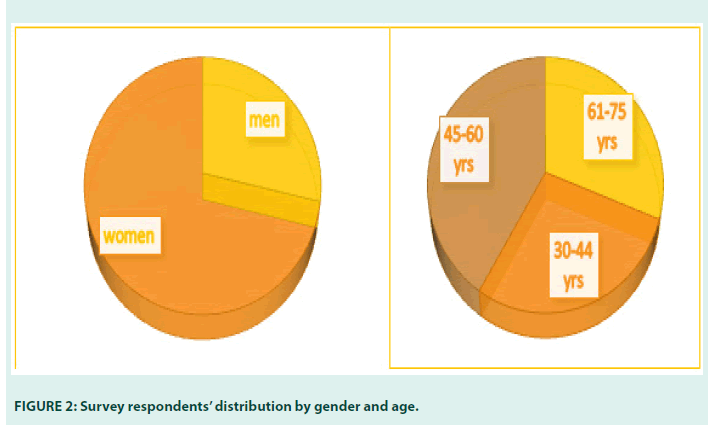

The questionnaire was fulfilled by 137 participants, age 53,69yrs ± 10,79, median 56years (min 32-max 73), with a greater prevalence of women (F vs. M: 71.5 vs. 28.5%, χ2<0,05) (FIGURE 2).

The most representative age group was 45- 60 years (43.1%), while each of the other two age range groups (30-44 and 61-73 years old) represented about a third of the entire population, respectively (FIGURE 2).

About half of the respondents (46%), regardless of gender, reported being victims of some form of violence during the practice of their medical assistance, more often in outpatient clinics and during day, mainly by men, while women appear to be somewhat more exposed to both verbal and physical violence.

Among those who were victims of violence, in 74.6% of cases this phenomenon occurred more than once.

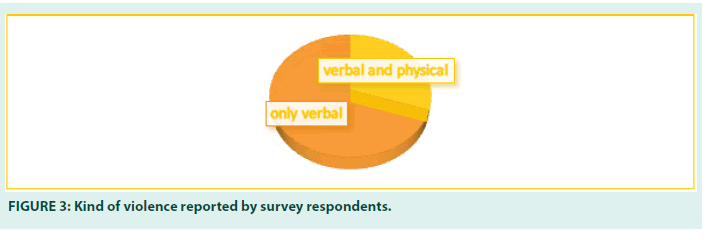

In most cases (70%) there was only verbal violence but in 30% of the cases physical violence was referred too. No sexual violence was reported (FIGURE 3).

Although no substantial gender difference has been detected among operators who have suffered violence attempts (46.15% men, 45.92% women, χ2 ns), women were more often subjected to both verbal and physical violence, in a higher percentage than in men (women vs. men: 31.11% vs. 27.78%, χ2 ns).

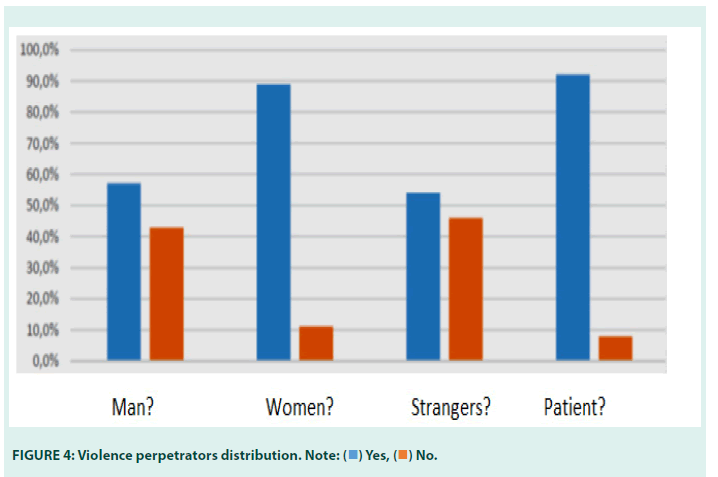

In most cases, verbal and physical attacks were perpetrated by patients, generally male, and more frequently strangers to the place (FIGURE 4).

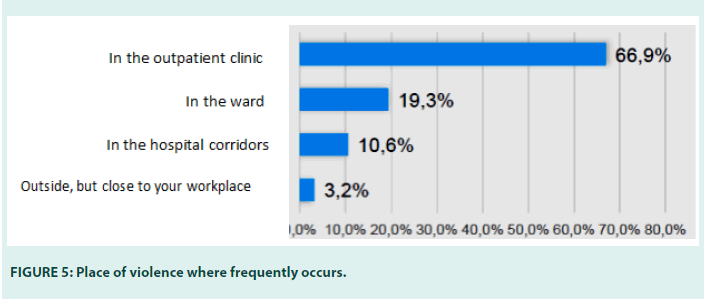

The outpatient clinic is the place where violence most frequently occurred (69.9%) (FIGURE 5).

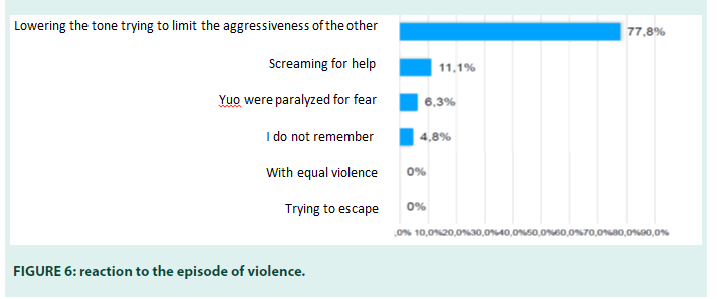

In most cases the event occurred during the day (90%). The most frequent reaction to the episode of violence (among 77.8% of the interviewees) saw the use of techniques of relaxation of the aggressor, such as lowering the tone of voice attempting to mitigate the assault.

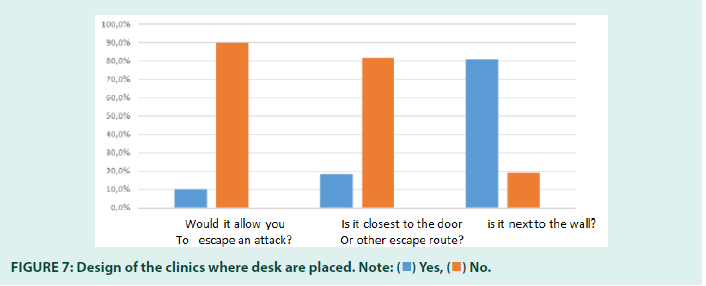

However, 11.1% of healthcare workers had to ask for help and in 6% without anyone helping. Moreover, 5% of subjects have erased the memory of the reaction to the violence suffered. No one attempted to escape even due to the design and furnishing of the clinics where desks are often placed next to walls and/or in positions with no escape route (FIGURES 6 and 7).

In line with what has just been said, in 70.9% of cases healthcare companies have not foreseen preventive strategies or actions to episodes of violence in the workplace. This leads to a greater perceiving in night shifts, when moving from one ward to another or upon arrival/exit from the hospital where 80.9% of the interviewees feel unprotected and in just over 28% there is a real possibility of asking for help if necessary. Where present, help strategies include telephone availability (90%) and only in a negligible percentage alarm systems. Specialized figures in charge of safety are present only in 55.5% of the structures where they are easily reachable by telephone in the 64.5%.

Discussion

One hundred thirty-seven diabetologists partecipated in the interview, with a much higher prevalence of women, likely because they are mostly in Italian diabetes services, but perhaps also because they are more sensitive to phenomenon.

About half of the respondents (46%), regardless of gender, reported being victims of some form of violence during the practice of their medical assistance, regardless of gender, more often in surgeries, during daytime, and mainly by male patients, while women appear to be a little more exposed to the risk of both verbal and physical violence even though the differences did not reach the statistical significance.

Unlike what is reported by WHO (www.who. it) and/or by some Italian evidence, where being female gender and nurse was associated with a 2.6 times and about 4 times higher risk for the presence of aggression, respectively, we did not find any association between victims’ age, gender and any type of violence as well as with the health care setting (territorial, hospitals), probably because of characteristics of the medical diabetologists interviewed (age, majority of women) [9].

No difference was found among subjects who have experienced violence on more than one occasion. This result can probably be explained by the observation of a global phenomenon, but we cannot rule out that some health professionals, for personal characteristics or context, are more involved, especially when the services and/or the healthcare settings do not provide prompt available and effective strategies for rescue and/ or escape routes. Perception of insecurity prevails in the passage between wards and at the entrance and/or exit from the structure.

In the field of diabetes, violence mainly occurs in local outpatient clinics where clinical assistance is a daytime activity although in some cases, it also occurs inside complex hospital units where care is provided in wards at day and night-time and during on-call shifts.

From data analysis on sentinel events from the Ministry of Health on reports from 2005 to 2012 “acts of violence against the operator” are in the 4th place among those reported to the Information system for the Monitoring of Errors in Healthcare but they certainly are underestimated [10].

This phenomenon is partly conditioned by the low propensity to report these incidents, as well as by the lack of standardized procedures for managing these events. Moreover, as required in 2007 by recommendation number 8 of Italian Ministry of Health, “acts of violence against healthcare professionals constitute sentinel events that require the implementation of appropriate protection and prevention

initiatives”[11]. In scope different factors combine to increase acts of violence, some of which are linked to the intrinsic characteristics of patients themselves (individual, attitudinal, etc.), others related to work environment (situational, organizational, etc.) [12]. Therefore it is necessary not to underestimate the multiple consequences of WPV in the sanitary field. In addition to physical consequences, acts of violence often cause repercussions on working activity (reduction of productivity and quality of care) and psychological sphere (depression, bournout) [13,14]. The negative consequences of such widespread violence significantly impact on the delivery of health care services, with deterioration in the quality of care provided.

Setting up a violence prevention program should be a goal national and regional health system aimed at ensure safety and quality of care in the workplace.

Recommendations/guidelines must be drawn up and updated in parallel with training of operators for the acquisition of specific skills and techniques and in response to violent actions especially when physical, a phenomenon that mainly affects women [15].

The analysis of various work situations can allow the identification of higher risk activities and, basing also on structural and environmental characteristics, the identification and implementation of suitable prevention measures.

In parallel developing models to improve the access to care, tailoring clients flow, scheduling appointments properly, keeping waiting times, suiting needs and resources would lead to a more favorable climate.

Unfortunately health costs often are associated to an unsatisfying clinical offer also due to the restricted working time requested to the health operators for each visit. The actions for management of the “risk of attacks on healthcare personnel” must be spread throughout the country and they should also be specific to each care setting.

They all imply a re-evaluation of the organizational model including procedures for reporting acts of violence against health care operators in all its forms.

For these reasons, violence against health workers must have a rightful place in the Risk assessment, with development of specific prevention programs that take into account various work situations and the involvement of operators from whom proposals for organizational improvement could arise the standard of care.

Taking measures to improve the work organization such as staff increases, adaptation of furnishings and design of working environment, provide security measures, prepare and support health workers, respond quicky and properly to incidents if they occur, encourage reporting, recording and monitoring of all incidents, ensure a confidential complaint or grievance procedure, monitor violence trends and the effectiveness of preventive measures [16].

Any health care facility, whatever the size, the location (urban or rural) and the type of services provided, (major referral hospitals of large cities, regional and district hospitals, health care centres, etc) is to be prevented by recognition of overall responsibility according to national legislation and practice, creating a climate of rejection of violence, monitoring mechanisms, recognizing the social factors that support or generate workplace violence also in diabetes centers.

Findings highlight the importance of taking into consideration work-related factors when designing interventions to prevent and address workplace violence in healthcare settings.

Conclusion

We do need national policies and plans to prevent and combat health workplace violence as this is not an isolated, individual problem but a structural, strategic problem rooted in social, economic, organizational and cultural factors A policy should be developed and promoted to attack the problem at its roots, involving psychologists and all social parties concerned and taking into account the special cultural and gender-dimension of the problem.

References

- Stahl-Gugger A, Hämmig O. Prevalence and Health Correlates of Workplace Violence and Discrimination Against Hospital Employees - a Cross-sectional Study in German-speaking Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 22(1):291 (2022).

- Phillips JP. Workplace Violence Against Health Care Workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 374(17):1661-9 (2016).

- Xiao Y, Na Du, Jia Chen, et al. Workplace violence against doctors in China: A Case Analysis of the Civil Aviation General Hospital incident. Front Public Health. 374(17):1661-9 (2022).

- Prevalence and Health Correlates of Workplace Violence and Discrimination Against Hospital Employees - a Cross-sectional Study in German-speaking Switzerland

- Cristina Civilotti, Sabrina Berlanda, Laura Iozzino. Hospital-based Healthcare Workers Victims of Workplace Violence in Italy: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(11):5860 (2021).

- Ramzi ZS, Fatah PW, Dalvandi A. Prevalence of Workplace Violence Against Healthcare Workers During the Covid -19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 13(2): 896156 (2022).

- Cebrino J, Portero de la Cruz S. A Worldwide Bibliometric Analysis of Published Literature on Workplace Violence in Healthcare Personnel. PLoS One. 15(11):e0242781 (2020).

- Nicola Ielapi, Michele Andreucci, Umberto Marcello Bracale, et al. Workplace Violence towards Health Care Workers: An Italian Cross-sectional Survey. Nurs Rep. 11(4): 758–764 (2021).

- Martinez AJ. Managing Workplace Violence with Evidence-based Interventions: A Literature Review. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 54(9):31-6 (2016).

- Wax JR, Pinette MG, Cartin A. Workplace Violence in Health Care-it's Not "Part of the Job". Obstet Gynecol Surv. 71(7):427-34 (2016).

- Hacer TY, Ali A. Burnout in Physicians Who Are Exposed to Workplace Violence. J Forensic Leg Med. 69(2):101874 (2020).

- Jennifer Davids, Margaret Murphy, Nathan Moore, et al. Exploring Staff Experiences: A Case for Redesigning the Response to Aggression and Violence in the Emergency Department. Int Emerg Nurs. 57:101017 (2021).

- Li YL, Li RQ, Qiu D, et al. Prevalence of Workplace Physical Violence against Health Care Professionals by Patients and Visitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(1):299 (2020).

- Health WISE Action Manual. Work Improvement in Health Services. International Labor Organization and World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland (2014).

- Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector: The Training Manual. ILO/ ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. International Labor Organization. Geneva, Switzerland (2005).

- Carla Barros, Rute F Meneses, Ana Sani, et al. Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Work-Related Predictors of Violence Behaviours. Psych. 4(3): 516-524 (2022).

)Yes,(

)Yes,( )No.

)No.