Case Report - Imaging in Medicine (2017) Volume 9, Issue 1

Uncommon parastomal hernia containing stomach: CT findings and review of literature

Ruslan Asadov1, Taha Yusuf Kuzan1, Rabia Ergelen1, Tolga Demirbaş2and Davut Tüney1

1Department of Radiology, Marmara University School of Medicine,Ä°stanbul, Turkey

2Department of General Surgery, Marmara University School of Medicine, Ä°stanbul, Turkey

- *Corresponding Author:

- E-mail: tykuzan@gmail.com

Abstract

A parastomal hernia is an incisional hernia related to an abdominal wall stoma. Parastomal hernia occurs frequently after the formation of a colostomy or ileostomy and it is the most common late stoma complication. Contents of parastomal hernia almost exclusively are limited to the mobile structures of the abdomen. Parastomal hernia including stomach is extremely rare. We describe a case of parastomal hernia containing stomach in a 65 year old woman who underwent rectal resection and left lower quadrant colostomy two years ago for rectal adenocarcinoma. The patient was presented to our emergency department with abdominal pain, vomiting and upper abdominal distension proceeding for 2 weeks. Abdominal CT revealed mild gastric dilatation associated with a parastomal hernia that contained the gastric corpus and antrum. The parastomal hernia was manually reduced. After 7 days, the patient fully recovered and was discharged. Parastomal hernia may contain stomach in patients presenting with obstructive symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, the current case has been published the ninth of such cases. Although rare, the present case is noteworthy in highlighting both the importance of being aware of this entity as well as radiologic confirmation to make correct diagnosis.

Keywords

stomach, parastomal hernia, CT.

Background

Stoma is an intestinal fistula created in emergency or by elective indications, and is done to drain the digestive tract content. Intestinal stomas may be created temporarily or permanently within the small and large intestine. A parastomal hernia is an incisional hernia related to an abdominal wall stoma [1- 3]. Parastomal hernia occurs frequently after the formation of a colostomy or ileostomy and it is the most common late stoma complication [4].

Parastomal hernias are classified into four subtypes: interstitial, where the hernial sac lies within the layers of the abdominal wall; subcutaneous, where the sac of the hernia lies in the subcutaneous plane; intrastomal, where the sac penetrates into a spout ileostomy; and peristomal (prolapse), where the sac is within a prolapsing stoma. The incidence of parastomal hernia has been reported to be between 0 and 48.1 per cent depending on the type of stoma and the length of follow-up. Most parastomal hernia is asymptomatic but may produce problems ranging from mild parastomal discomfort to life-threatening complications, such as strangulation, perforation and obstruction [4-6].

The contents of hernia sac are almost exclusively limited to the mobile structures of the abdomen including omentum, small bowel and colon [4-6]. Parastomal hernia including stomach is extremely rare. Only few cases have been reported in the English literature [7-14]. Herein, we present another subcutaneous type parastomal hernia containing stomach and underline the importance of being aware of parastomal hernia may contain stomach.

Case

A 65 year old woman was presented to our emergency department with abdominal pain, vomiting and upper abdominal distension proceeding for 2 weeks. Her medical history included rectal adenocarcinoma, for which she underwent rectal resection and left lower quadrant colostomy two years ago. Laboratory data revealed normal white blood cell count, normal liver parenchyma function, normal renal function and normal coagulation tests except for CRP: 16.3 mg/L (normal range: 0-5 mg/L). The remaining parameters also were normal. On physical examination, abdominal tenderness and a large parastomal hernia in left lower quadrant was palpated.

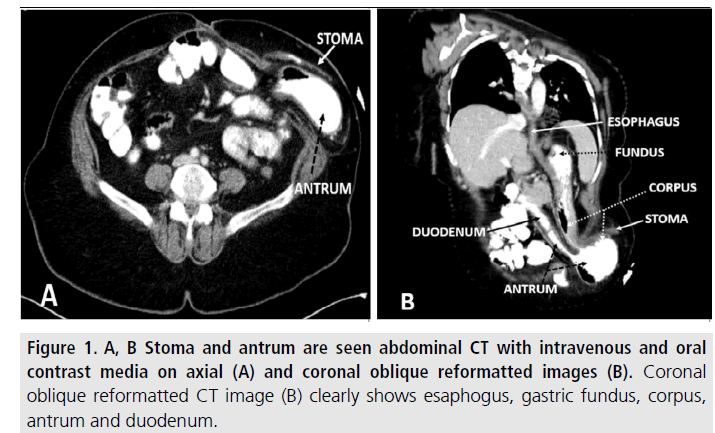

Abdominal CT examinations were performed using a 256 section Somatom Definition Flash (Siemens Medical Systems, Forchheim, Germany) with intravenous and oral contrast media. Mild gastric dilatation associated with a parastomal hernia that containing gastric corpus and antrum are demonstrated on axial (FIGURE 1A) and particularly on coronal reformatted images (FIGURE 1B).

Figure 1.A, B Stoma and antrum are seen abdominal CT with intravenous and oral contrast media on axial (A) and coronal oblique reformatted images (B). Coronal oblique reformatted CT image (B) clearly shows esaphogus, gastric fundus, corpus, antrum and duodenum.

The patient refused surgical treatment. Therefore, parastomal hernia was manually reduced. After 7 days, the patient fully recovered with a normal oral intake and discharged.

Discussion

Gastric involvement into abdominal wall hernia sac is very rare. There have been a number of reports in the English literature demonstrating parastomal hernia containing stomach (TABLE 1). TABLE 1 also summarizes the characteristics of all cases including age, gender, medical history, clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment and result. To the best of our knowledge, current case has been published the ninth of such cases.

| Cases | Age | Gender | Case History | Presentation | Investigation Diagnosis) | Treatment | Final Diagnosis | Outcome and Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figiel and Figiel [7] | 75 | F | Sigmoid carcinoma, a few days ago transverse colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | GI series/laparotomy | Explorative laparotomy | Stomach and gangrenous bowel in parastomal hernia | Death |

| Mcallister and D’Altorio [8] | 91 | F | Diverticulitis,3 years ago Sigmoid resection with a Hartmann pouch and Left paraumblical colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | GI series | Explorative laparotomy | Incarcerated stomach in parastomal hernia (body, antrum) | Full recovery |

| Ellingson et al. [9] | 77 | F | Diverticular bleeding, 3 years ago Sigmoid resection with a Hartmann pouch, Left paraumblical colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | GI series | Explorative laparotomy | Incarcerated stomach in parastomal hernia (antrum, pylorous) | Full recovery |

| Bota et al. [10] | 41 | F | Crohns disease, 10 years ago panproctocolectomy and end ileostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | GI series | Explorative laparotomy | Incarcerated stomach and small bowel in parastomal hernia | Wound enfection*/recovery |

| Ramia-Ángel et al. [11] | 64 | F | Rectal cancer, 17 years ago abdmino-perineal resection-LLQ colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | Abdominal CT | Manual reduction | Stomach in parastomal hernia (antrum) | Full recovery |

| Ilyas et al. [12] | 93 | F | Sigmoid carcinoma, 4 years ago Sigmoid resection - Hartmann's procedure LLQ colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | GI series/Abdominal CT | Explorative laparotomy | Gastric emphysema and incarcerated stomach in parastomal hernia | Full recovery |

| Marsh and Hoejgaard [13] | 81 | M | Rectal cancer, 19 years ago Rectal resection - LLQ colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | Plain film | Explorative laparotomy | Bowel and Incarcerate and perforated stomach in parastomal hernia | Wound enfection*/recovery |

| Barber-Millet et al. [14] | 69 | F | Sigmoid adenocarcinoma, 9 years ago Sigmoid resection with a Hartmann pouch and LLQ end colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | GI series/Abdominal CT | Explorative laparotomy | Incarcerated stomach in parastomal hernia (antrum) | Full recovery |

| Our case | 65 | F | Rectal cancer, 2 years ago abdmino-perineal resection LLQ end colostomy | Gastric outlet obstruction | Abdominal CT | Manual reduction | Stomach in parastomal hernia | Full recovery |

*** M: Male; F: Female; GI: Gastrointestinal.

Table 1. Review of literature.

The rarity of gastric herniation is explained in part by the numerous ligamentous attachments that keep the stomach relatively fixed in the abdominal cavity. Besides ligaments, the esophagus and diaphragm tend to hold the stomach superiorly, and the duodenum anchors it inferiorly and its mobility restricted. An abdominal wall facial defect must coexist with sufficiently lax gastric ligaments to permit gastric migration and herniation is a hypotheses suggested to explain the mechanism of gastric parastomal hernia [9].

Our patient was 65 year old multipara obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) woman. Similarly with the literature, all the reported cases of parastomal hernia containing stomach except one are advanced age women (ranges: 41-93 years). We think it may be related to prior pregnancy, obesity and laxity of ligament with aging. But we have not data about it.

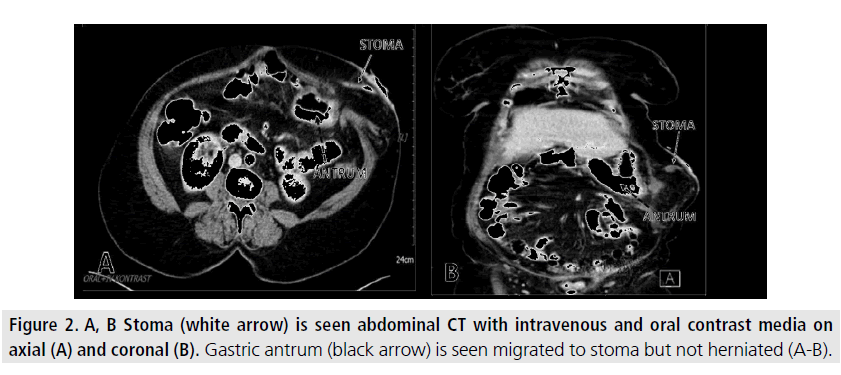

In our case parastomal herniation of the gastric antrum and corpus were seen oblique abdominal CT reconstruction with intravenous and oral contrast on axial (FIGURES 1B). Antrum is the most common gastric part in parastomal hernia sac as seen in our case. The other gastric part reported in the parastomal hernia sac include gastric corpus and pylorus [8,9,11,14]. We retrospectively examined one year before CT images of our patient and realized that the antrum had tend to migrate towards to stoma but not herniated exactly (FIGURES 2A-B).

All the patients presented with partial or complete gastric outlet obstruction symptoms including abdominal discomfort, pain, nausea, vomiting, obstruction, and strangulation. Five of the nine patients had incarcerated stomach, two had reductable stomach, one patient had incarcerated and perforated stomach and one patient had gastric emphysema and incarcerated stomach in parastomal hernia at the time of diagnosis. Our patient presented with abdominal pain, vomiting and upper abdominal distension similar with literature [7-14]. Due to our patient’s reluctant to surgery, the hernia content was manually reduced and after 7 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged without complications.

All cases in literature except one the stoma formed elective indications and stoma aged between 2 and 19 years. The other stoma formed emergency indications and the patient died because of gangrenous intestine and colon a few days later. Seven of nine cases in literature treated with explorative laparotomy. The remaining cases including our patient were manually reduced. All cases except one fully recovered after explorative laparotomy or manual reduction in a short time [7-14].

The diagnosis of parastomal hernia is usually established with physical examination, followed by clinic and radiographic evaluation. Abdominal CT not only shows parastomal hernia but also confirms parastomal hernia contents and complications including perforation and gastric emphysema. Due to the widespread use of CT, it has become easier to diagnose parastomal hernia in patient with gastric outlet obstruction. However, in a series fluoroscopic examination of upper GI tract was able to demonstrate five of six parastomal gastric herniation but one confirmed with explorative laparotomy [7-10,12,14].

Conclusion

In summary, parastomal hernias are common complication following stoma construction and its diagnosis is not difficult. However, parastomal hernia may contain stomach in patients presenting with obstructive symptoms secondary to stomach herniation in the parastomal hernia. Although rare, the present case is noteworthy in highlighting both the importance of being aware of this entity as well as radiologic confirmation to make correct diagnosis.

Figure 2.A, B Stoma (white arrow) is seen abdominal CT with intravenous and oral contrast media on axial (A) and coronal (B). Gastric antrum (black arrow) is seen migrated to stoma but not herniated (A-B).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pearl RK. Parastomal hernias. World. J. Surg. 13, 569-572 (1989).

- Hyland J. The basics of ostomies. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 25, 241-244 (2002).

- Krokowicz L, Slawek S, Ledwosinski W et al. Surgical methods of treatment of intestinal passage disturbances with the characteristics of constipation in patients with intestinal stoma based on own experience. Pol. Przegl. Chir. 87, 160-165 (2015).

- Sohn YJ, Moon SM, Shin US et al. Incidence and risk factors of parastomal hernia. J. Korean. Soc. Coloproctol. 28, 241-246 (2012).

- Carne P, Robertson G, Frizelle F. Parastomal hernia. Br. J. Surg. 90, 784-793 (2003).

- Devlin HB. Peristomal hernia. In Operative Surgery Volume 1: Alimentary Tract and Abdominal wall (4th edn), Dudley H (ed.) Butterworths: London, 441-443 (1983).

- Figiel L, Figiel S. Gastric herniation as a complication of transverse colostomy. Radiology. 88, 995-997 (1967).

- Mcallister JD, D'Altorio RA. A rare cause of parastomal hernia: stomach herniation. South. Med. J. 84, 911-912 (1991).

- Ellingson TL, Maki JH, Kozarek RA et al. An incarcerated peristomal gastric hernia causing gastric outlet obstruction. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 17, 314-316 (1993).

- Bota E, Shaikh I, Fernandes R et al. Stomach in a parastomal hernia: uncommon presentation. BMJ. Case. Rep. (2012).

- Ramia-Ángel J, De la Plaza R, Quiñones-Sampedro J et al. Gastrointestinal: Gastric incarceration in parastomal hernia. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 27, 1405 (2012).

- Ilyas C, Young A, Lewis M et al. Parastomal hernia causing gastric emphysema. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 94, 72E-73E (2012).

- Marsh AK, Hoejgaard M. Incarcerated and perforated stomach found in parastomal hernia: a case of a stomach in a parastomal hernia and subsequent strangulation-induced necrosis and perforation. J. Surg. Case. Rep. 4 (2013).

- Barber-Millet S, Pous S, Navarro V et al. Parastomal Hernia Containing Stomach. Int. Surg. 99, 404-406 (2014).